A guide for anchorites

The dictionary tells me that anchorages are places of safe harbor, where one can presumably drop a toothed iron into a sea bed and expect it to keep you in place, unmoved by storms or tides. The act of being at anchor. But anchors—and anchorages—are, after all, by nature meant to be a temporary station. All anchors get pulled up at some point.

Living in Anchorage can sometimes feel like the anchors of all anchors, one I can’t seem to shake. I keep tugging, testing, waiting.

Anchorage is surrounded by mountains and sea, yet neither are places of access. They are places of bold indifference. Highways are two: north and south—not the winding backroads that connect to another state, another landscape. Options for getting out are a 3-hour flight to Seattle, the nearest US city by proximity, or driving more than nine hours on broken macadam, twisted by cycles of freeze/thaw, to reach Canada’s Yukon.

And in the way that the pandemic brings ironies into a focus so sharp it can cut: When I first moved here, I really grew to miss the anonymity of a crowd (back when that was possible and not a major risk). The lack of escape, the small-ish city with limited options where everyone seems no more than three degrees removed from one another was something I couldn’t get used to. I missed opportunities to be anonymous, in the rambling way that a change of scene and being alone in a city can offer. To have space to imagine ourselves differently, rather than through how a few others claim to know or define us.

Being alone so often draws to mind quiet, solitary experiences. But not all solitude requires removal from society—sometimes it requires immersion in it writ large. I think the most alone and free I’ve ever felt was in New York or London—the exhilaration of life visible at all hours of the day and night, the pulse of traffic, the companionship of strangers—that parallel comfort of knowing you’re not alone in being alone.

Virginia Woolf wrote, in her essay Street Haunting:

As we step out of the house on a fine evening between four and six, we shed the self our friends know us by and become part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude of one’s own room.

I missed—and still miss—that army of anonymous trampers in a city, the unfamiliar crowd, the companionship of company without conversation. People side by side drinking coffee, perusing books, walking sidewalks, crossing streets.

Living in small-town/pandemic world is similar to the pull of the objects in our own rooms—as Woolf goes on to write:

which perpetually express the oddity of our own temperaments and enforce the memories of our own experience.

Our relationships with being alone have, needless to say, changed over the last two years. And I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to live anchored to the places where we live. The weights that tie to us, that stop our movement. But also the same weights that steady us in rapid currents, that find gravity when we most need its pull. Anchors are nuanced; they can be a false promise, temporary—not an act of permanence, but inherently a stop on the way to something else—a stop in the tides or current, a stop on the journey onward. At the same time, they are a weight that can pull us back when we think we want to steer forward. We come to accept their weight in case of need.

The word anchor is traced to a mix of styles that situate its roots in Greek, Latin, and Old English—ancor, borrowed from Latin anchor—meaning crooked, curved. When I read the etymology I felt the word already offering more than I had expected: I thought of the curved and crooked paths it takes to arrive in a place, of the curved and crooked ways of this particular place—the hold that an anchor offers and the potential betrayal of that promise. A burden, a reassurance, a faith, a lie. An anchor can be the weight of something unasked for, holding back movement and drawing us into an undertow. But it also grants the power of refusal—the power to claim a stasis and refuge that would otherwise be impossible.

Anne Carson writes about these types of contradictions in her beautiful essay Decreation:

why should the truth not be impossible? Why should the impossible not be true? Questions like these are the links from which prayers are forged.

Freedom is not often the first thought that comes to mind when one reads about anchorites.

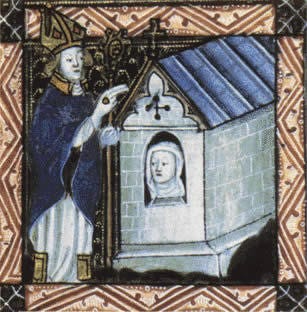

Anchorites withdrew from the world purposefully—to modern eyes one of the most extreme forms of asceticism. And certainly, it was not for the faint of heart—it typically meant enclosure in a small cell (on average 12’ square) and would be dependent upon a dedicated patron and attendant. Each cell was supposed to have three windows—a “squint” to be able to observe mass and receive the eucharist, a window to an attending servant’s quarters, and one to the outside. There were some instances where sisters lived as anchorites together, or with an adjacent garden, and an adjoining parlor for the attending servant, but this was uncommon. Mostly it was a solitary life, requiring immense self-discipline and spiritual commitment in a very specific confined space for life.

Some tracts referred to it as a “living death”—as a person is enclosed, the burial liturgy would often be sung as they are sealed in the liminal space between life, grave, and eternity. The anchorite was admonished to dig the soil of their cell as a reminder of their own grave and mortality, in order to stay focused on the eternal.

Yet while their enclosure into these small spaces seemed to remove an anchorite physically from the world, they were in fact rooted to the center of their community. Many anchorholds were situated in prominent, central locations—either attached to a church, or sometimes along routes of procession or pilgrimage. They most often would have access to observe church services, and were consulted by members of the community for insight, prayer, and wisdom. Some anchorites were famously consulted by kings.

So while the privations appear extreme to modern eyes, in many ways it was an anchorite’s pledge to fight battles of sin on behalf of society that endeared them to their communities. In a preface to the 13th century Ancrene Wisse (or Guide for Anchoresses), written for three sisters about to embark on the anchoritic life, Hugh White writes

…anchorites are the spiritual crack-troops, particularly heroic operatives in the fight against the forces of evil…the personal combat of the anchorite may be regarded as the engagement of a common enemy, and as such an activity not wholly directed to the welfare of the self.

By the 13th and 14th centuries, anchorites had become an integral part of medieval life. The majority of anchorites at that time, particularly in England, were women.

Given that medieval women had little protection without a father or husband, the anchoritic life may not have been an unattractive proposition—women were often married in their teens, and their identities were essentially erased—a wife became the property of the husband. A wife would also face the dangers of repeated childbirth, often with years of pregnancy and childrearing. Life would be spent in service to the household and all its labors. And in an age where literacy rates were very low and not encouraged among laity, the anchoritic life also importantly offered a means to learn, read, and write. The author of the Ancrene Wisse advised his sisters specifically to read:

The remedy for sloth is the spiritual joy and the comfort of glad hope through reading, through holy meditation, or from man's mouth. Often, dear sisters, you should pray less in order to read more. Reading is itself good prayer. Reading teaches how and what one should pray for, and prayer acquires it afterwards. In the middle of reading, when the heart is pleased, a devotion (or, reverence) comes up which is worth many prayers.

By entering the privacy of enclosure, it allowed the anchorite access to a wider public than a woman typically could have access to—able to create a wider idea of self, place, and time. An anchorite took root in place, able to speak with a voice that would come to be both prophetic and wise to those around her—a mother to all, with access to an ironic visibility. It’s not difficult to imagine that the “living death” of an anchoress—with the literal assurance of a home for life, financial support, and needs attended to—offered an option that for some women would be more attractive than the erasure of a forced marriage. Anchorites were able to excavate the truths of language and symbol and claim what was otherwise denied to women.

I’m reminded of anchorites in reading Annie Dillard’s luminescent Holy the Firm:

Held, held fast by love in the world like the moth in wax, your life a wick, your head on fire with prayer, held utterly, outside and in, you sleep alone, if you call that alone, you cry God.

Unsurprisingly, mystic women and anchorites produced some of the earliest devotional literature. One of the more widely known of these works is Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich, an anchorite enclosed in a cell adjacent to the church of St Julian at Conisford in Norwich in the 14th century. Not much is known about Julian other than her writings—by some accounts, the earliest work by a woman in English—clear-eyed descriptions of spiritual visions, which she experienced while gravely ill, and then wrote of in more detail later in her life. It's thought that as her work relies on the imagery of motherhood—and specifically describes God as a mother—that she was perhaps a widow, who most likely lost her family in the plague that was moving through England. Margarey Kempe—another mystic who wrote perhaps the first autobiography in English—records traveling to visit Julian to obtain spiritual advice, saying she was "bidden by Our Lord" to go to "Dame Jelyan ... for the anchoress was expert in" divine revelations, "and good counsel could give."

I imagine Julian of Norwich in her cell, hearing the spiritual and physical world around her, reading, conversing with God, experiencing visions, held fast by love in the world, her head on fire with prayer. Offering counsel and being left in revered quiet to do combat on behalf of the world-weary. And to write.

Describing one of her visions, she wrote:

I was filled with eternal certainty, strongly anchored and without any fear. This feeling was so joyful to me and so full of goodness that I felt completely peaceful, easy and at rest, as though there were nothing on earth that could hurt me.

Julian’s words were recovered in the 1570s, but remained obscure to many until a manuscript was rediscovered in a donation to the British Library, and a new edition was published in the 1910s. It was at that point that the public became familiar with her most often quoted summation:

All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.

Gerda Lerner, writing about mystics, wrote:

All the great mystics, male or female, described such experiences [mystic visions], often in words that managed to express the inadequacy of words.

The dream-like quality of mystic revelation, and the inadequacy of normal language—feels as if it is describing the realm of poetry, where language is stretched into new meanings.

So it’s not surprising that T. S. Eliot incorporated Julian’s lines in Little Gidding, a poem that is a part of Four Quartets (1943), a series of poems that discuss time, perspective, humanity, and salvation:

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.— T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding, Four Quartets

Marguerite Porete, a 13th-century mystic from France—who believed so fervently in circulating and publishing her book that she was burned at the stake for it—describes her experience of the divine as the FarNear. Anne Carson wrote about Porete’s use of the term, writing “I have no idea what it means but it gives me a thrill.” I too feel that thrill when I hear it. While it seems to pair opposite or contradictory ideas, the word has a sense and meaning that makes me want to spend time with it—to explode the two words and pull them back together, to see what lands.

I haven’t been able to get the FarNear out of my head after reading it—a line of music, the smashing of words etching out a feeling of deep clarity, as the contradictory dissolves into a new thing altogether. Like Julian’s writings, the FarNear is poetry. It leads us to sit with the contradictions in our lives—the longing for both solitude and connection, privacy and exposure. Similar to Keats’ idea—“capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” For the impossible to be true and the truth to be impossible. To long for a return to a new normal that will no longer accept the lies that so much of what we’ve known of normal has sanctioned.

So I’ve been drawn lately to spending time with opposites and contradictions—sometimes obvious in their simplicity, but moving beyond irony to become something more precise.

And I had a similar sense in thinking about anchors and anchorites—the power of a new meaning when it includes space for its opposite. Particularly in these pandemic years of seclusion, isolation—an anchor that stubbornly is being dragged along by so many. The pandemic anchorhold of now.

Enclosure as a means to freedom. The weight of an anchor offering ties that both bind and release. The power that solitude and place offer at the same time as they isolate. The hold an anchorage can have on the psyche—and what meaning it has after years of knowing its intricate weight.

What I’ve feared about the Anchorage I’ve lived in—like other anchors that stubbornly remind us of gravity’s pull more often than we would like—is that it would anchor me to a place that was not mine to call home. But in the space between is where I’ve now spent half my life, where I became a mother, where my son has grown up, where I’ve said goodbye to two soulful dogs and hello to three new ones, and where friends have become family—another contradiction that when you are in places far from home, you often create close bonds with those who are near. Another type of FarNear.

Anchorage has become a place that I have a sneaking suspicion I will only be able to move away from when I no longer want to live or be someplace else—when I accept its messiness and indifference on its own terms. Then I know I’ll be able to leave.

In writing about the FarNear, Anne Carson continues on to describe a prayer of Sappho:

a kletic, a calling hymn, an invocation to God to come from where she is to where we are. Such a hymn typically names both of these places, setting its invocation inbetween in order to measure the difference.

I was thinking of this as I thought of Julian writing to the future in her anchorhold, the space between god and herself, between her now and ours. That bearing witness to the days and hours—writing about these days and hours—is a hymn to measure the distance. Between god, if you are so inclined to believe, but also between the past and present, present and future, the distances between all of us whether at home or in the broader mix of the world. How our calling hymns might make sense of the distance that has been imposed on us—or that we created.

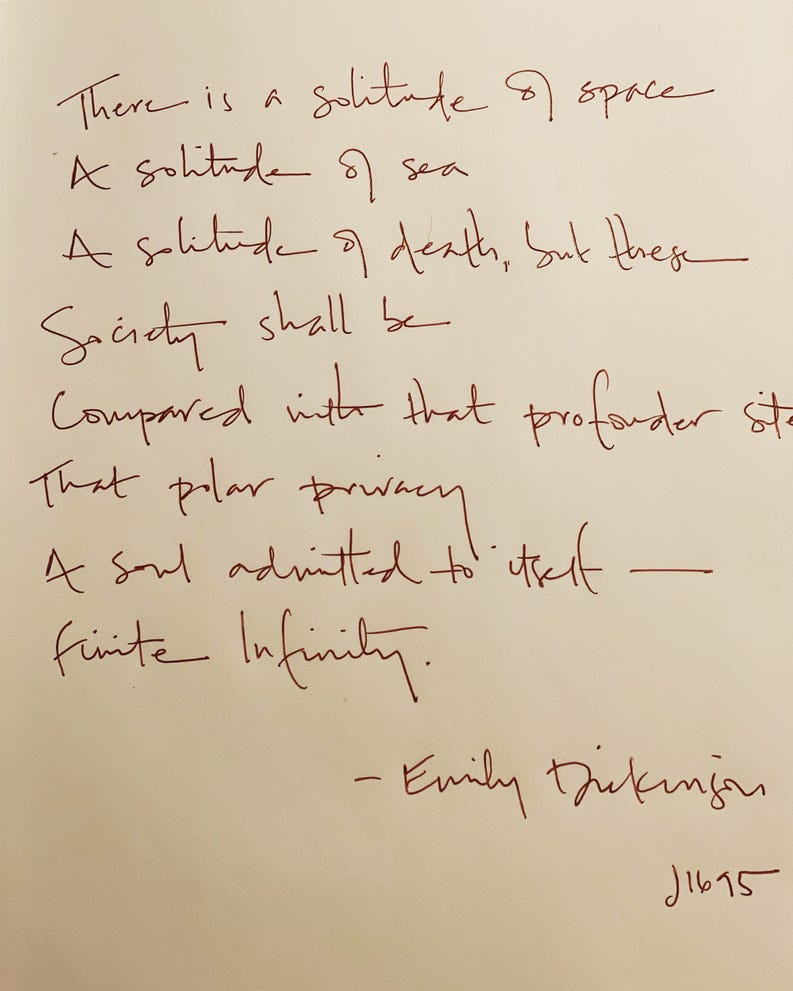

Anchorites seem to hint at the importance of marking that distance, of calling to it, observing it, writing about it. And I can’t help but think of Emily Dickinson, creating her own anchoritic life—and the atoms she split in her own poetry of hymnal distance. She chose her cell, her room and found freedom (“Mattie: here is freedom”) using thresholds and windows as squints, observing life around her, and writing about it in ways that exploded language. She went to battle by creating an identity for herself that refused the role that others would claim for her. Her commitment to her anchorhold—like Julian—gave the world language and beauty that it had never yet heard.

And then—the size of this “small” life— The Sages—call it small— Swelled—like Horizons—in my vest— And I sneered—softly—"small!"

“Soto”—Explore Thyself— Therein—Thyself shalt find The "Undiscovered Continent"— No Settler—had the Mind—

The Heart is the Capital of the Mind— The Mind is a single State— The Heart and the Mind together make A single Continent— One—is the Population— Numerous enough— This ecstatic Nation Seek—it is Yourself.

Sounding very Dickinson, the 11th-century monk Goscelin of St Bertin exclaims in his letter to the anchorite Eve of Wilton:

‘My cell is so narrow,’ you may say, but oh, how wide is the sky!

How to live in the anchorholds of now so that we can find spaces to imagine and create new ideas out of the worn grooves of routine, refuse the noise that tries so hard to tell us what to think about how to live in this world. How to be a part of a community in times of withdrawal—or of long anchorage.

Anchors latch on to different parts of us in ways that we sometimes can’t see, and in ways that we didn’t know existed. Scarless holds that beckon for return, that leave parts of its iron in the soft flesh of our feelings, identities, histories.

When I think of the pulls made on us—those of where we think we should or should not be, and the pull of a somewhere we’re still so uncertain of—I’ve begun to think of anchors as starting points to memory, a means to understand the distance between what might feel imposed but still offers safety in a coming storm. A connection that calls to god from where she is to where we are, so that we might measure the distance.

And write about it.

This is a triumphant piece, Freya. I kept thinking to grab bits and pieces to comment on but it deserves so much more. Ultimately, this near-closing bit....

"How to live in the anchorholds of now so that we can find spaces to imagine and create new ideas out of the worn grooves of routine, refuse the noise that tries so hard to tell us what to think about how to live in this world. How to be a part of a community in times of withdrawal—or of long anchorage."

... really sums up my struggle. As someone who thinks about solitude and hermits and withdrawal and all of it, this work resonates deeply with me. Thank you.