Witchcraft was hung, in History,

But History and I

Find all the Witchcraft that we need

Around us, Every Day -—Emily Dickinson

My mom is deep into genealogical research most days. It’s not unusual to get texts from her with some new ancestor story. Most of the time I brush these off—everyone is related to everyone when you go back far enough. While I believe in honoring ancestors, I can only feign interest because of the shame I feel that my ancestors all came here from somewhere else and contributed to the trauma and legacies of settler colonialism. But the story she shared last week I can’t stop thinking about: my tenth great grandmother was the last woman executed for witchcraft in the Connecticut witch trials in 1662, thirty years before the infamous trials of Salem. And Connecticut was also the place of the first witch confession in New England.

The roots of the word confession come from the 14th century—around 100 years before the first description of witchcraft was written in 1485—from Latin we get “to acknowledge,” with con “together”+ fateri”—to admit, to speak, to tell, to say. The original religious sense was based in the idea of avowing one’s faith in spite of persecution, without suffering martyrdom—an interesting distinction. From that sense, we also get in Old French a figurative sense that meant “to harm, hurt, make suffer.”

I’m interested in the con+ part of this etymology—that the act of confession is not an individual act. A confession requires an audience. And yet what can be a cathartic and redemptive act—to confess and be heard, to be absolved—can also be the means of ensuring persecution or execution.

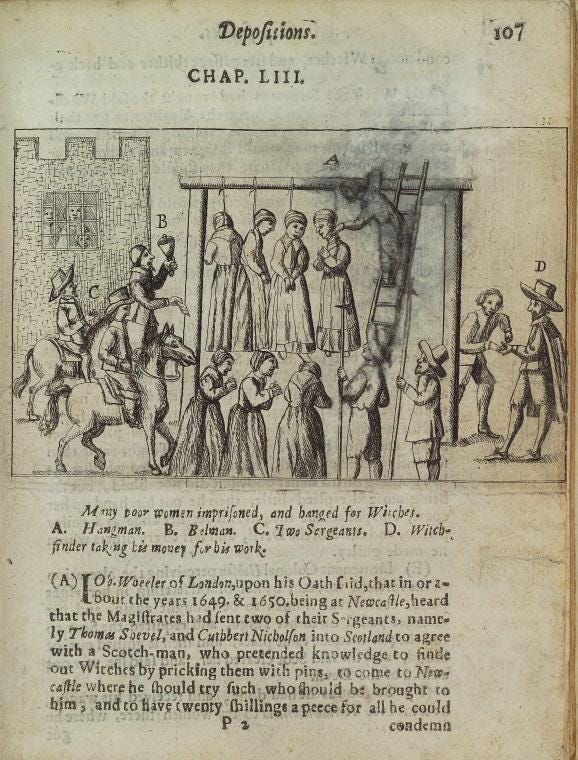

The act of confession opens up an assumed truth—-something that is revealed, avowed, professed. Saints confessed of their faith and were assured of resurrection; Catholics confess to a priest and receive absolution; and yet witches—80% of whom were women—confessed, only to be executed.

When I began to write poetry, I primarily wrote with the voice of an observer. I wanted to note the moment-ness of specific places, feelings, experiences. Later in grad school, a writing professor asked my poetry cohort to examine the role of “I” in our poems—and I could find none. And as a result, I realized that my early poems didn’t really work as I wanted them to. They lacked energy, need—there was no real investment of emotion. And as a result, they didn’t invite the reader to engage from their own experience, to be a part of a more intimate conversation of experience—to recognize the outlines of themselves in what I wrote. Without placing myself within the work, it lacked a sense of opening. It’s counterintuitive, but without the personal, there is no possibility of cracking open the universal—the means of mutual recognition.

For the same reason that I was uncomfortable with putting myself on the page, I had been reluctant for a long time to read so-called ‘confessional’ poetry—Plath, Sexton, Rich, Olds, Howe—writers who unflinchingly gaze into their own experience, in the catharsis of avowing their hurt. Their “I” on the page scared me—to harm, hurt, make suffer. I suspected their work would act as a mirror, reflecting my own tendencies to anxiety, depression, and take me farther than I wanted to go emotionally. I’ve always had to get used to the temperature of the water, and could never jump into a pool cold. I didn’t want to invest in their writing. Just as I hadn’t really invested myself into my own.

Once I challenged myself to read confessional poets’ work, I became a bit obsessed with it—by the power women writers, in particular, displayed in confessional poetry—the fullness of both emotion and art, placing themselves at the forefront of their experience. Reading it invited me to let go of feelings I had somewhat foolishly recognized as solely my own. Like all good poetry, it was an emotional release—the catharsis that opens up a wider sky of understanding. And the understanding is how universal feelings of suffering, of distress, are—particularly, in this case, the suffering of women under society’s demands.

It is poetry that encourages looking outward rather than solely inward. It demands an audience—to be read, to be acknowledged, to bear witness. Their work is not only about the self, it’s about society—that is what these poems proclaim so loudly. These are not poems of one woman; these are poems that point to the experience of all women. And it was intensely freeing to read them, chipping away at the ideas that society so often admonishes us—that one’s feelings are solely one’s own to fix, alone. Confessional poetry—if we are to still label it that—is effect, squarely turning its eye outward at cause.

In the confessions of women convicted of witchcraft, you can trace the constraints that women were bombarded with—the limited agency a woman had in Puritanical society. Their hurt is evident in every part of their confessions.

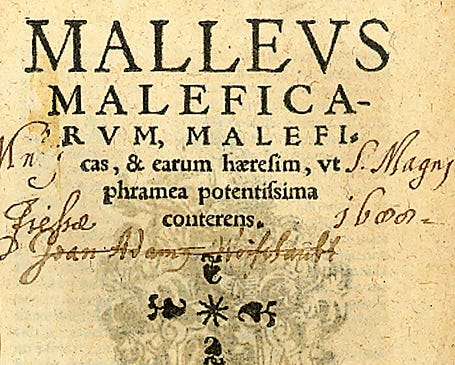

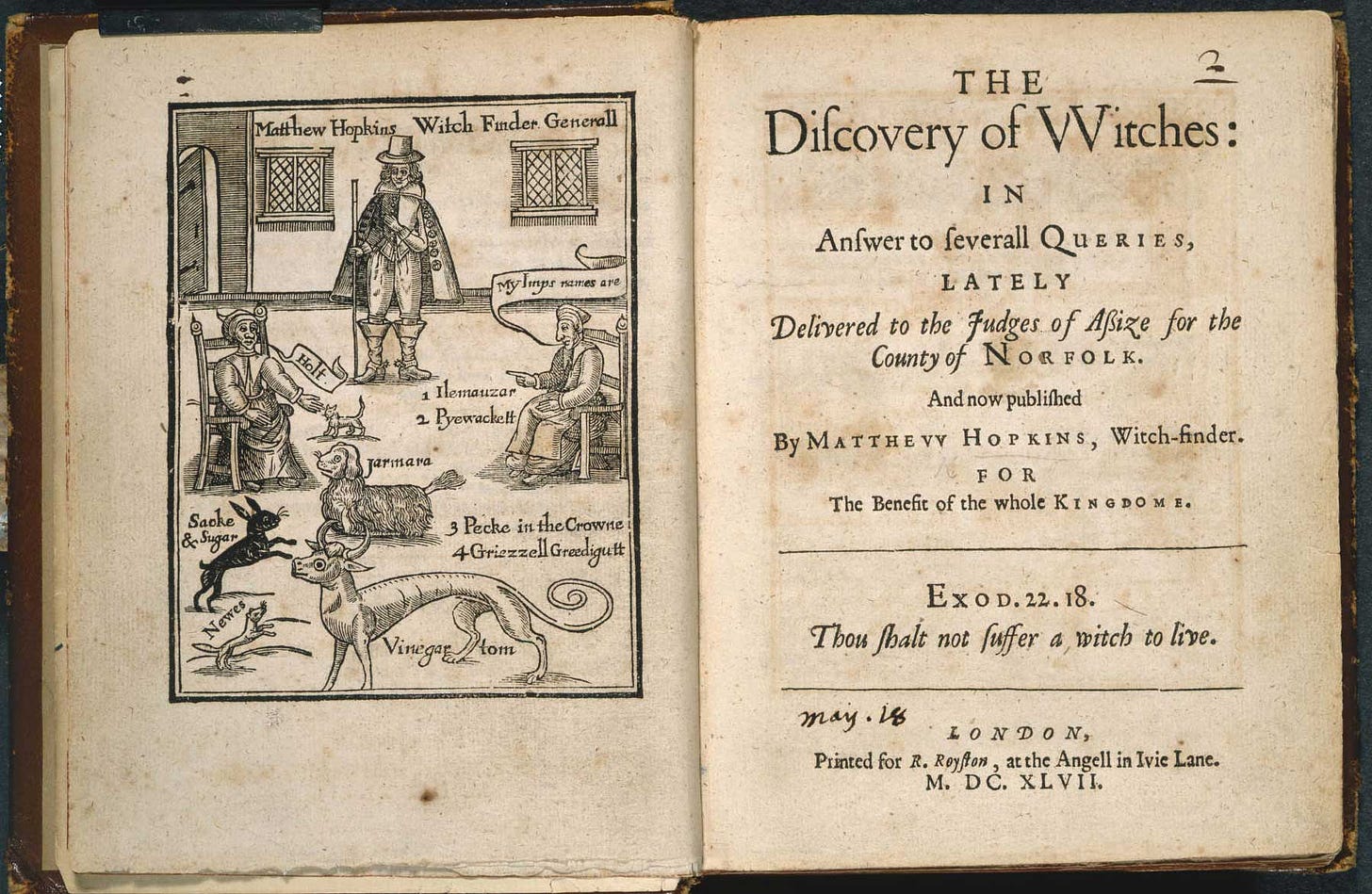

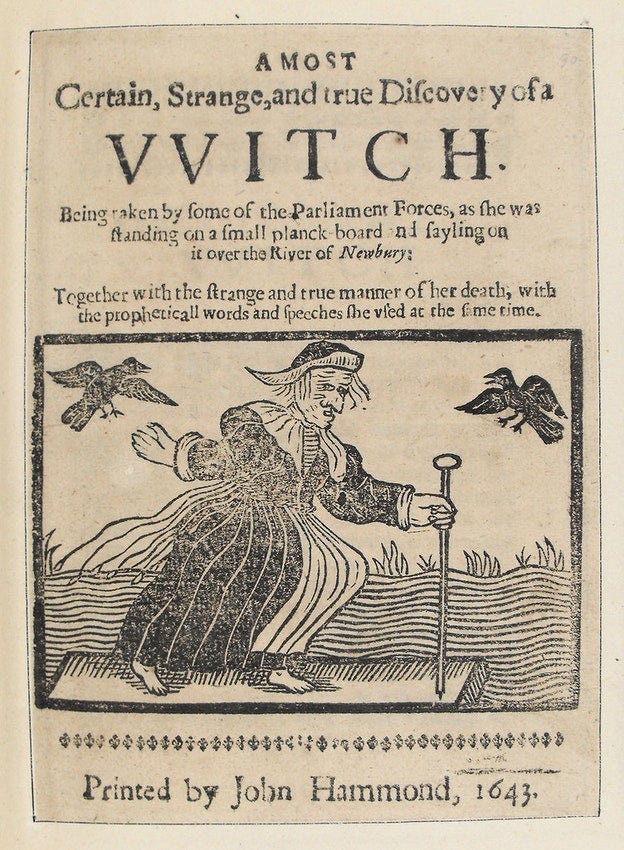

While horrific physical and psychological torture was used in many cases to force an accused witch to confess, there were still many confessions given without physical torture—only with the emotional distress of ministers who admonished that an accused witch could “doe wronge yor selfe but cleare your conscience.” Women accused of being a witch were asked to judge themselves in the eyes of God, within a social morality that was highly controlled, prescribed, and specific. Women were responsible for the original sin Puritans labored under, conditioned to believe they were weak, unworthy, the lustful daughters of Eve. The Malleus Maleficarum portrayed the simple fact of being a woman as threatening, deviant, and subversive—strongly inclined towards witchcraft.

Being a woman was a sin. A confession was essentially admitting to what was already known.

As witch hunts flamed through New England, women likely questioned themselves and their experiences through the lens of witchcraft. Many women were swept into trials as witnesses and as accusers, listening to the details of witchcraft accusations and seeing the ramifications firsthand. Women policed other women who failed to live up to the ideals of womanhood—reflecting the precarity of a woman's position, and the fear of the witch hunter’s gaze turned towards themselves.

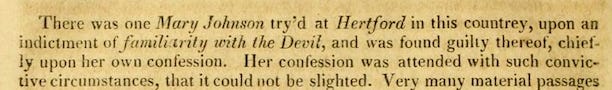

Extremities of emotion had little language in Puritanical New England. Suicide attempts were often attributed to falling under the temptations of the devil. Feelings of inadequacy, of shame, of fear, of not meeting the demands of ideal domestic womanhood—let alone experiences of miscarriage, rape, abuse, or of raising one’s voice to a husband or an otherwise perceived defiance of authority—all could be understood as a sign of the devil’s influence. With very few trials seeking justice for rape, there was little language to describe sexual assault and abuse—victims would be forced to keep such abuse silent, likely ascribing the blame to themselves—that they were responsible and had fallen under the devil’s influence. Women who confessed to witchcraft were made to confess to the failure of being the good mother, the good wife, the good neighbor that society deemed they should be.

Louise Jackson, writing on witches’ confessions in England at the same time as those in Connecticut, writes

As victims, they are seeing themselves at fault and blaming themselves for what has happened….These cases clearly show that the accused women, in their confessions, were judging themselves as wives and mothers—they were judging their angers, their bitterness, their fears, and their failures to live up to the expectation of others.

‘Confessional’ has been used as a pejorative adjective and applied disproportionately to poetry written by women (Gill, 20).

There is a throughline in witchcraft confessions and the ‘confessional’ poetry written by women in the mid-twentieth century—and it extends to modern non-fiction written by women that is often labeled ‘self-help,’ and even to why the largest consumer of self-help books are women. Women have been told for centuries that their stories—their madness, their despair, their depression, their poverty, their anger—are something that they need to confess to or learn to fix. Alone.

Women are not rewarded for the truth-telling of their experiences. Much like the witch’s ‘confession,’ the truth-telling women first labeled as confessional poets were punished or excluded from what was considered ‘high verse,’ or literature. In a 1977 interview with Paris Review, Richard Wilbur criticized Confessional poetry, saying,

One of the jobs of poetry is to make the unbearable bearable, not by falsehood, but by clear, precise confrontation. Even the most cheerful poet has to cope with pain as part of the human lot; what he shouldn't do is to complain, and dwell on his personal mischance.

Almost in response to such criticism, Adrienne Rich—often labeled a confessional poet—wrote

…honesty in women has not been considered important. We have been depicted as generically whimsical, deceitful, subtle, vacillating. And we have been rewarded for lying.

Confess and be executed, or be silent and lie to yourself instead.

Confessional writing and witchcraft confessions act as almost a mirror reflecting between centuries—both serve as testaments to the crushing weight of social strictures and expectations, of institutional beliefs and practices that rob women of agency and demands their silence. Depression, suicidal thoughts, abortion, poverty, desire, anger, abuse—this is what ‘confessional’ poetry looks at unflinchingly and breaks the silence and lies society insists on keeping. By looking inward, confessional poetry—like witchcraft confessions—bears witness to the truth of women’s marginalization.

It’s the visibility of trauma in witchcraft confessions that is so heartbreaking: impoverished servants accused of theft; single women with unwanted pregnancies considering abortion, or the death of a child to avoid further poverty; abused women confessing to wishing a husband would fall ill. Women who found themselves widows too young, or widows too old. Single women who dared to show a spark of independence. Epidemics of loss that needed someone to blame.

Women in the decades following World War II were called on to return to their ‘natural’ place—to create a domestic atmosphere and standards of perfection that remained within the strict confines of the domestic space. The 1950s and 1960s—the decades that Plath, Sexton, and Rich began writing in—was a time where women were urged to prioritize the home—to be good wives, good mothers, good housekeepers, good neighbors.

As women who suffered depression and struggled under the role that society insisted on for them—who railed against the pressures of wifedom and motherhood—Plath and Sexton wrote their confessional art as acts of rebellion. Their poetry subverted the norms of poetry at the time, just as women who were accused of witchcraft were thought to be subversive to what a woman should be. As artists and as women, Plath and Sexton saw the futility of the small frame of space afforded to a woman and wrote about it—how it made them feel, think, create, and in both cases, consider (and ultimately die by) suicide. Their work resoundingly would not be silent.

The devil that brought accusations of witchcraft—and dismisses women writers labeled confessional—is patriarchy.

My ancestor, Mary Barnes, left no confession, voluntary or coerced. She was born in England in 1631, and moved with her husband to settle a new community in Connecticut. At 32, with four children, she was accused of witchcraft and brought to trial. Scant records claim that her husband was an elder in the church, but that Mary was not a member of the church. One account mentions that she was considered a ‘free-thinking woman.’

The trial court’s decree condemning her is so matter of fact about her fate:

Mary Barnes thou art here indicted by the name of Mary Barnes for not having the fear of God before thine eyes, thou hast entertained familiarity with Satan, the grand enemy of God and mankind — and by his help has acted things in a preternatural way beyond human abilities in a natural course for which according to the law of God and the established law of this commonwealth thou deservest to die.

She was tried and executed within three weeks. Mary’s five-year-old daughter died soon after her death. Another account states that her husband did not attend the trial, but paid for her imprisonment. Her husband re-married three months later to their neighbor’s daughter, who in some accounts was also the family’s prior nanny. His new wife was half his age.

Records state that Mary Barnes pleaded not guilty and asked for a trial by jury. The jury returned that they found her guilty of the charges made against her. I can’t help but think that her not guilty plea and request for trial are evidence that she was desperate to be heard.

I want to shout this from the rooftops -- with just one edit. Please say "died by suicide" rather than "committed suicide." Please don't blame the victim for "committing" such an act of desperation. -- with love from the mother of such a child

This is thought provoking and vital. And telling ... it would take no small amount of encouragement for the "patriarchal authorities" to return to such judgments if only they could get away with it, and it seems all too likely an idea that it could happen. It DOES happen, if less directly, more behind the curtain. It's horrifying.