Hi friends—

I’ve been working on a different essay with some overlapping themes that’s taking a bit longer to write, and as I’m headed out of town soon, I suspect I won’t be able to finish it until (hopefully) next week. So in the meantime, I wanted to share an essay from the archive. As always, with so much appreciation for your time, interest, and attention.

It’s equinox as I write this (or was yesterday). I was planning to write about other topics whirling in the background, but to be honest, I can’t ignore the color of the trees, the new caps of snow on the mountains (that looks like it might stay and expand), the birds flying south noisily. It’s beautiful. It’s cooler, it’s cozy, it’s melancholy in a way that is reflective and comforting in some way. Dusk is returning in earnest to this latitude, both in mornings and evenings.

I look out my window and it is glowing yellow, only a few leaves hinting at the green they once were. Since the leaves are so demanding of attention and I can’t ignore the glow they’re giving off through the windows, despite the grey sky, I was thinking of fall, and of how it still has echoes of earlier times when it was so wedded to harvest. That, instead of fall, or autumn, this time of year was called harvest. Fall is an earlier term for autumn, and somehow it held on as a relic in North America, which is why Americans so often say fall, while those in the UK will more commonly say autumn.

Twilights are long in the North during the summer, but they hold a different quality of light—gradations of color, la madrugada, the blue hours. The dusk that returns in the fall becomes shorter again—the kind of dusk that announces the coming of night. As we hit equinox, and the nights begin to grow longer and more noticeable on this side of it, it’s the time of year when lights start to again become necessary, after hardly needing to be turned on for months. And it’s the time that dusk returns, that feeling of day turning to true night once again.

Of course, I’ll doubtless complain about the darkness once it comes back in full force, that December-January malaise that takes over and feels like it will never end. But for now, it’s that equitable equinox of the light that is a type of solace, an equity that you can feel between night and day, a type of balance that makes you believe everything that becomes polarized can perhaps find a similar balance, at least temporarily.

The Romans divided up night differently than we do, without regular clocks and watches to time every minute. Dusk was crepusculum, and dusk is sometimes still described as crepuscular, although so many words that refer back to earlier times too easily fall away. Gloaming is another word for the dusks of earlier times—taken from the root for glow—perhaps referring to that feeling of the last glow from the sun before night sets in. It’s a term that held on in Scotland, and Robert Burns re-introduced it into common use.

The Greeks called dusk lykóphos, which means ‘wolf-light,’ and is echoed in German wolflicht, and French entre chien et loop—literally between dog and wolf. Night for when the wild side of us can roam free for a time. In preindustrial England, Venus could be so bright that it was called ‘shepherd’s lamp’—to help guide those last dogs to bed before the wolves might appear.

I often think about how different the world was before electricity lit up our skies and world. I read that in Scandinavia, dusk was a time to pause—too dark to continue with work either indoors or out, but too early to justify the cost of burning a candle or lamp. It was called the “twilight rest,” a time for rest, prayer, conversation. Candle-lighting time was only arrived at when it became truly too dark to see—with layers of color and gradations of dusk that are doubtless unknown to us now. Burning a candle too early was referred to as ‘burning daylight', a wasteful exercise.

I’ve been thinking about this all week, particularly on dark rainy days (the kind I have loved my whole life but only have been able to enjoy up here this year, one of the wettest late summer/falls on record for Anchorage). I’ve been testing the light to see how much I can write or work without a light. And after reading about burning daylight, and thinking with chagrin about how quickly we burn energy, turned the lights off when I realized that really, it’s still much too light to be able to enjoy the glow of a candle. I wonder when candle-lighting time will truly come to the North again—maybe I’ll keep a record this year of the gradations of light as we move towards solstice now, away from the small fulcrum of balanced day and night. The lights we have today are so much brighter than any candle from the past—some candles only glowed enough to make the darkness visible. And I can’t stop thinking about that idea, of making the darkness visible.

“What is more conducive to wisdom than the night?” asked St. Cyril of Jerusalem.

As I was thinking about all of the dusk and gloamings to come with equinox, I started reading more about night and came across this passage in A. Roger Ekirch’s book At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past:

Routinely, the darkness of night loosened the tethers of the visible world. Despite night’s dangers, no other realm of preindustrial existence promised so much autonomy to so many people….Night alone permitted the expression of man’s inner character…. “Everything belongs to me in the night,” declared Restif de la Bretonne. “We can fix our eyes more comfortably on the heavens,” observed Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle—“our thoughts are freer because we’re so foolish as to imagine ourselves the only ones abroad to dream.

It reminded me of Virginia Woolf’s essay “Street Haunting,” where she also spoke about the freedom that accompanies the arrival of dusk:

The evening hour, too, gives us the irresponsibility which darkness and lamplight bestow. We are no longer quite ourselves. As we step out of the house on a fine evening between four and six, we shed the self our friends know us by and become part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers, whose society is so agreeable after the solitude of one's own room.

The autonomy and freedom that night offers gained my attention, given how much I have always been a night owl. I am indeed guilty of what in modern parlance has been declared, rather rudely, “Revenge Bedtime Procrastination.” While many news articles want to define this as a symptom of the modern screen era, a problem to be solved, or a dire symptom of today’s hustle culture, it isn't at all new (and might not be dire). The night has offered autonomy to people for centuries, and many have taken advantage of the quiet and solitude that darkness offers after the demands of the well-lit day.

“Night makes me bold,” wrote George Herbert.

In a different section of At Day’s Close, Ekirch goes on to write about the freedom recovered at night in the past:

Naturally, members of the middle and upper classes, by retiring to their bedchambers, enjoyed the greatest opportunity for personal reflection. Still, as early as the mid-1600s, many laboring families resided in homes with more than just a single room; plus there were occasions, on pleasant evenings, to retreat to a barn or shed. In the late fifteenth century, the Parisian servant Jean Standonck labored by day at a convent only to ascend a bell tower at night to read books by moonlight. Thomas Platter, as a rope-maker’s apprentice, regularly defied his master by rising silently at night to learn Greek by the faint glow of a candle.

As reading became a more solitary activity by the fifteenth century—a time when people began to read silently rather than aloud in company as was common before—soon aphorisms and beliefs arose that darkness was made for solitude, study, meditation, and prayer. And for writing. “It smells of the candle,” was a saying for texts that held the melancholy flavor of nighttime musings.

Revenge bedtime procrastination isn’t a revenge on ourselves, it’s a revenge on social control. The night is a time when many can finally find time to themselves while the cares and work of the day sleep.

The freedom of night was vital for Emily Dickinson—she even negotiated with her father to hire a maid so that she could avoid the morning household chores, and stay up to write when the household was asleep, not waking until late in the morning.

So many women, poor, and marginalized people through centuries and today, who have no free time during the day, have been able to revenge procrastinate their bedtime into brief windows of nighttime that resemble more autonomy, more sovereignty, more freedom to be who they have wanted to be.

One such woman writer was Laura Cereta, who wrote:

This grand volume of epistles, for which the final draft is now being copied out, bears witness, letter by letter, to whatever muses I have managed to muster in the dead of night.

Ekirch writes of Laura Cereta’s nighttime habit of writing and studying:

[Writing at night] was one of the joys of Laura Cereta, the young wife of an Italian merchant in the late fifteenth century. Responsible for helping to maintain her parents’ household as well as her own, she found rare freedom at night, especially from males in her family, to cultivate her many talents.

I love that he mentions Laura Cereta (1469 – 1499), but he understates her significance. She was one of the early feminist thinkers of fifteenth-century Italy, admired by many, and famous for her writing and her mind. Not only a wife of or daughter of, as Ekirche introduces her in his text, Cereta was a formidable scholar and prolific writer during her short life. She was known as “one of the best scholars in Brescia, Verona, and Venice in 1488-92,” and her writing was notable for prioritizing the friendship of women.

Cereta’s letters addressed themes across personal memory, women’s education, marriage, and war—and she openly sought immortality through writing. Of the importance of her ‘revenge bedtime procrastination’ habits she wrote:

my sweet night vigil of reading….I have no leisure time for my own writing and studies unless I use the nights as productively as I can. I sleep very little. Time is a terribly scarce commodity for those of us who spend our skills and labor equally on our families and our own work. But by staying up all night, I become a thief of time, sequestering a space from the rest of the day.

Cereta’s mother was a businesswoman and her father a magistrate, and they believed in educating their daughter. Cereta spent much of her early years in a convent, where she could spend time studying Latin and many other subjects. It was the prioress who became her mentor and teacher, and who first taught her the value of the night—teaching the young Cereta to use the time from late at night to early dawn for studies and writing while others slept.

Cereta was interested not only in moral philosophy and writing, but also in math, astrology, and agriculture. She was married at fifteen, widowed at seventeen, and died at 30. But within that short life, she assembled her letters into a manuscript book that was circulated widely throughout Italy among scholars and writers, and yet it was not published until the seventeenth century.

Of her feminism, an example is this fiery speech to one of the many men who criticized her:

My ears are wearied by your carping. You brashly and publicly not merely wonder but indeed lament that I am said to possess as fine a mind as nature ever bestowed upon the most learned man. You seem to think that so learned a woman has scarcely before been seen in the world. You are wrong on both counts, Sempronius, and have dearly strayed from the path of truth and disseminate falsehood…You pretend to admire me as a female prodigy, but there lurks sugared deceit in your adulation. You wait perpetually in ambush to entrap my lovely sex, and overcome by your hatred seek to trample me underfoot and dash me to the earth.

There lurks sugared deceit in your adulation. Damn, that’s good. And rings true over five hundred (!) years later.

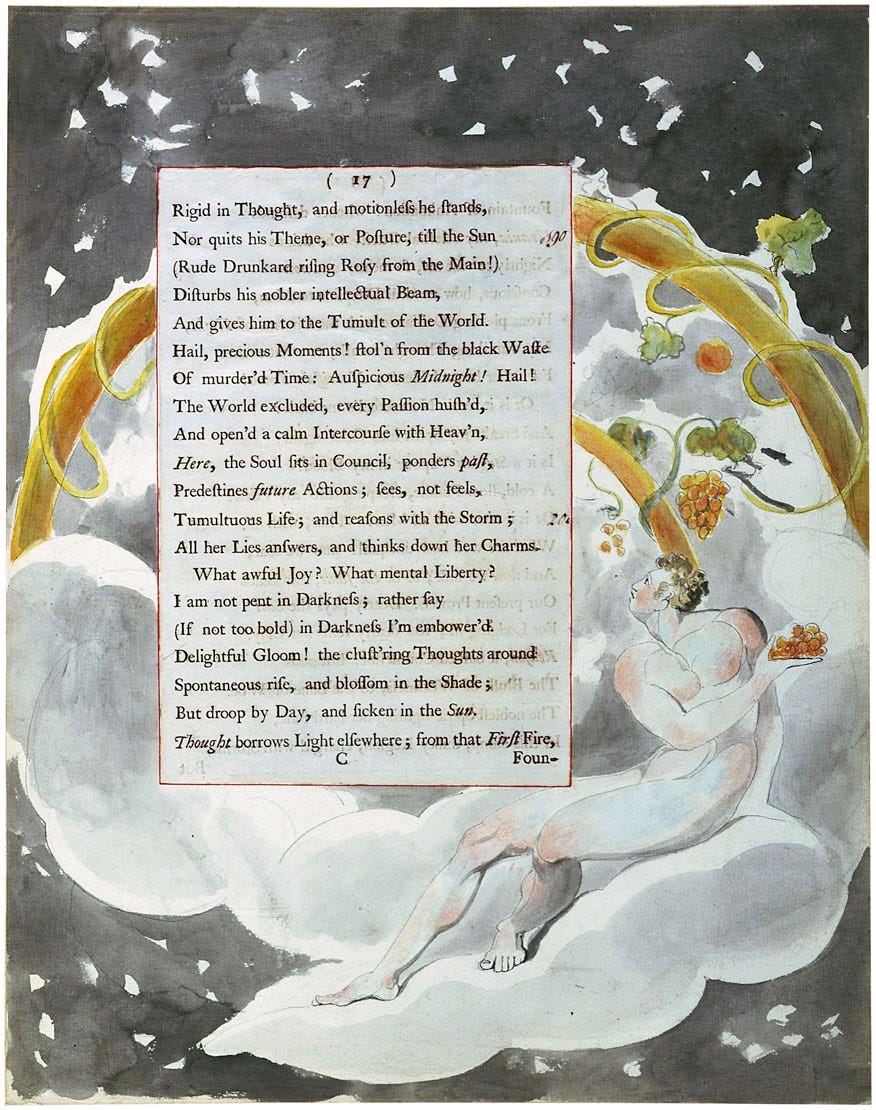

Edward Young, who wrote a series of blank verse poems called Night Thoughts in 1745, wrote:

What awful joy! What mental liberty!

I am not pent in darkness;

…in darkness I’m embowered.” Young believed so much in the liberating creativity to be gained at night that he would close his curtains at midday and light a lamp to recreate its magic.

I haven’t attempted to re-create night through the summer months (aside from a blackout blind that I am grateful for), but I have missed its quiet, its blanket sameness that allows the noise of the world to dim a little, to feel the quiet that only really happens in darkness.

I welcome the returning dusk, the cooling air, the falling leaves, the first sign of snow, the returning pause of twilight and darkness falling. Too soon it will overtake both morning and night (the greedy surfeit of high latitudes), but for now, I am grateful for the balance of equinox, the hush of dusk, the blurring of what’s visible, and the quiet assurance of night.

Night is when the world recedes, when we can be ourselves, and take revenge against the hustling of daylight if we must. As Nabokov writes in Pale Fire, unlike almost anything else, the turn of dusk into night is:

…gradual and dual blue / As night unites the viewer with the view.

I love how you always relate history, female writers and nature in one beautiful web of revelations Freya! Love this so much

This post reminds me of Joe March from little woman who would often burn the midnight’s oil to get her scripts together. The urge of working through night to reclaim who we are and hour of the wolf are the allegories I deeply need for self transformation. Thank you for providing me with such tools and knowledge. 💜🌼

Always loved the word “gloaming.”

One thing I love about going off-grid is the immediate rewiring of relationship to light and dark. Electric lighting seems so offensive to the senses after a few days without!

Lovely writing, Freya, thank you. 🧡