Better language

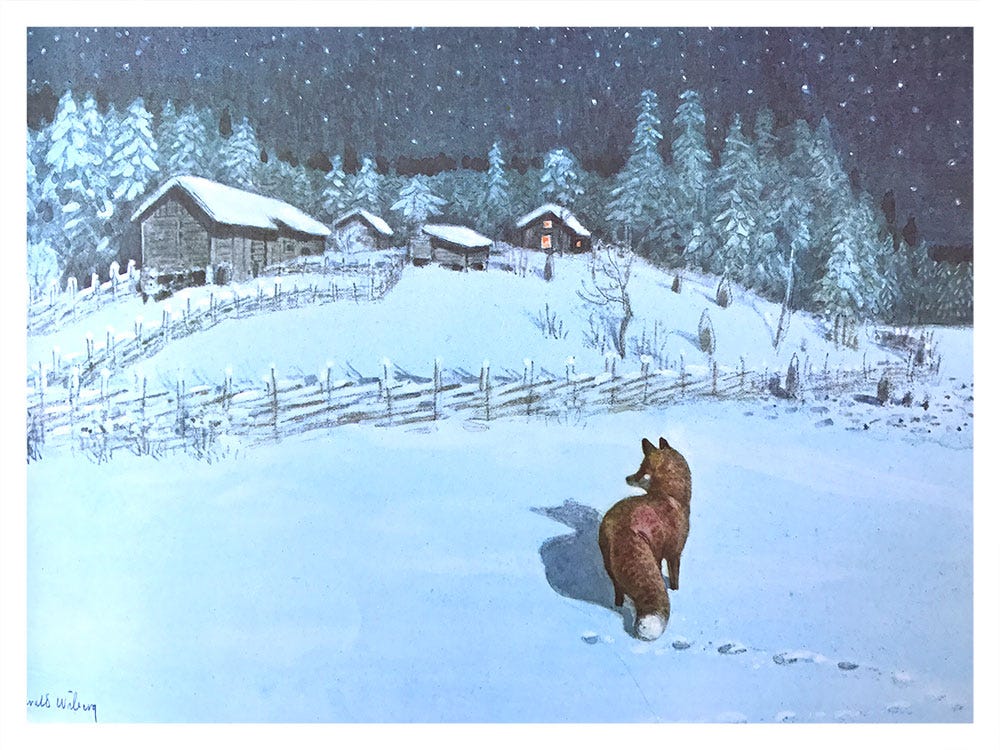

I was up late in the middle of the night once again, taking my insomniac dog out. I gazed at the patterns of birch shadow that crossed the deep snow behind our house while I waited. And to my delight, I was reacquainted with an old winter friend that I hadn’t seen since last year.

Last year my friend similarly arrived below the porch, where I keep nuts and seeds out for our feathered companions. Taking advantage of magpie messes, the visitor was doubtless looking for errant falls from full beaks.

The last time I saw them with very sleepy eyes, there was a light on outside that was bright enough to admire the copper shine of their fur, the length of their tail in detail. This time it was completely dark, a world only of shadow from distant street lights, maybe a bit of starshine as well. And with barely awake eyes, I watched as the fox moved in every way but linearly, moving across the snow—first taken aback by our presence, then returning to shapeshift across the snow. Snaking across the back, ottering upside down, squirreling into a circle, only to take off again slowly in a different direction, fully made of shadow.

In the late morning, the tracks in the daylight bore witness to the meandering dance. I showed my son and we delighted in the marks across the snow, around tree bases—the small tracks of furred feet creating the text of a nocturnal dance for us to read many hours later.

David Abram writes about how writing is thought to have been inspired by the tracks of animals left in the snow, in desert sands, in muddy riverbanks. Tracks of presence, a lingering step made permanent just enough to read later if the conditions are right.

Tracks left in the snow are made with purpose, deliberation—in an awareness of response. The winding steps were decisions made in conversation with the surrounding snow, the sparse light, other visitors unseen but smelled, the sound of our footsteps across the deck—all made in response to the surroundings, the landscape. This is not mindless language—each step pressed into the snow is essential to who and what it means to be a fox in low moonlight, in snow among birches.

Language holds a power of being—of a being in conversation with the world.

Each snow track is made by the body of an animal. Anima, meaning breath. That which breathes, that which is of the air. It’s language that is not only a sign to be read but was made by the breath of spirit, to be witnessed. It’s a text written with spare necessity and purpose, without excess.

Abram also wrote of the animate sense of language’s origin, how it holds a power that forms our world:

Only if words are felt, bodily presences, like echoes or waterfalls, can we understand the power of spoken language to influence, alter, and transform the perceptual world. As this is expressed in a Modoc song: "I / the song / I walk here"1

There’s been a lot of words written of late. Endless, compulsive, consumptive, orchestrated—on top of an already overwhelming (or underwhelming, depending on the angle) digital world. An increasing noise of rancor, hoping to drown out everything good in the name of free speech. A drowning cacophony of mindless, and yes, malicious, prose.

It’s just words, was a dismissive comment I saw several people say in the past weeks. Just like the rhyme we’re told to remember as children when bullied—sticks and stones are what break bones, not names, not words. Right?

Another line I’ve read recently, again, is that the more a certain word is used, the less meaning it contains, the less power it will hold. But it can’t run both ways.

Words do have power—by their very nature, their very meaning. Words break bones and heads and hearts. They arose from our breath, from our bodies. It’s why words cause shame and anguish unlike any physical injury—because they are tied to our bodies, whether walking across snow or in script on a page. While many words seem to live in an abstracted world, they are still ultimately tethered in the body.

Saying words over and over, assuming they’ll lose meaning is also a fallacy— because they become an invocation, a spell cast over the world, becoming a curse. Repeating language ad nauseam ignores the reciprocity of conversation. That we are all subjects of this world. No matter how many times these words are said, they will continue to hurt and harm.

Words said in the name of absolute free speech have become a sign that someone is being silenced for someone else’s power and greed.

In many Indigenous traditions, the name of an animal is not spoken aloud when hunting. Animals are relations, and referring to them as such, rather than by an objective name is a recognition of that kinship, of being in reciprocity with the world.2 The world and its kin are spoken to as fellow-subjects, as fellow-beings in and of this earth.

Many Alaskans who have lived here for a while have adopted something akin to this, using the phrase ‘Coming through’ to make some noise in Bear country, rather than the typical guidance of “Hey Bear!” that many park service guides instruct. One phrase is too close to invoking Bear to find us and ignores that we are in Bear’s home. The other tries to recognize that our paths overlap and wants to respect Bear’s space, to let them know we’re just passing through.

I recently read that this sense of a word’s power when it comes to our relationship with the world is something Western tradition has parallels in, but that has of course been completely forgotten:

…the word ‘bear’ is a euphemism. In many Germanic languages, including English, the word ‘bear’ literally means ‘the brown one’…a hunter’s taboo word for the animal…When it comes to bears, we straight up do not speak the name.3

While it isn’t exactly offering a sense of deference or relationship explicitly, it does include a sense that at some point, some western languages once also knew not to offend by presuming a familiarity that hasn’t been earned. Perhaps “Hey Bear” isn’t as specific, or as powerful, as we would think.

This tradition of saying-by-not-saying as a sign of respect is also in the traditions of fairies, elves, trows, jinn, gnomes, sidhe, and other magical entities believed to exist in a liminal world beyond our own in so many cultures. In many traditions, these entities are never spoken of by name—they’re referenced in Celtic tradition as the ‘good neighbors,’ ‘good people,’ even ‘people of peace,’ for instance.4 It’s a term that offers respect and assumes the good intentions of the beings around them while recognizing the power that they hold, and of not wanting to risk their ire by not holding proper deference. An awareness that language has the power to invoke, as well as to offer respect.

So much of the language we are flooded by is careless language. The power that can be inflicted outward with language is something barely mentioned in the vitriol of discourse today. And yet it is spun out in droves, in all manner of disrespect, harm, and violence.

We speak to have a return—to be witnessed, to converse. Words arise from bodies that breathe and are of this earth, none of which are external to us but live alongside us as subjects in relationship to one another. Reciprocity is a fundamental part of any word spoken into the world. It’s an act of communication, which implies community. What is said aloud— on snow or written and submitted across digital screens—causes a response, either directly or across distance.5 By showing deference to language, we acknowledge its power and treat it with the respect and invitation—or invocation—that it can be.

What we need is language that is truly radical—‘of the root:’

late 14c., “originating in the root or ground;” of body parts or fluids, “vital to life,” from Latin radicalis “of or having roots…”

We need words torn up by the roots, with rain and dew and earth still clinging to them6—not abstracted, cleaned of their relationship to the soil that bore them so that they can be sleeked into weapons. Not spoken and written only to cry they’re ‘just words.’ Why say them in the first place then? It’s never just words.

As Kate Manne has written, censure—judgment, condemnation— is not the same as censorship. To demand that platforms of power do not allow, let alone support and promote, hate speech is a direct response to the language that has been put out into the world. It’s the answer back that is invited when such lazy language is spoken. It is a collective response to the spell that would be cast on others, a curse that causes very real harm. A response to what has become weaponized under the false guise of ‘freedom of speech.’

Watching the past few weeks, I kept thinking of the words of Joan of Arc’s stunning retort to her interrogators—repeating in my mind like a type of chant, an invocation for language with rain and dew and earth still clinging to it:

When asked, “In what language do your voices speak to you?”

She answered: “In better language than yours.”

Abram, David. 2017. The Spell of the Sensuous. Vintage Books. p. 89

Weatherdon, Meaghan S. 2022. "Religion, Animals, and Indigenous Traditions" Religions 13, no. 7: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13070654

Zafarris, Jess. 2023. Words from Hell: Unearthing the Darkest Secrets of English Etymology. Chambers, John Murray Press. p. 265

Henderson, Lizanne and Edward J. Cowan. 2001. Scottish Fairy Belief. Tuckwell Press. p. 14

In the case of my visiting friend, their steps and gaze happened to turn toward me, and now their presence is here among my words, shared with you.

As Atlantic Editor Thomas Wentworth Higginson described Emily Dickinson’s poetry in his preface to her first posthumously published work.

This post informs a part of me I am already aware of but keep forgetting and thus need reminding from time to time - the power of language, the movements of spirits of nature in relation to all other elements around them. Ohh what beauty does your writing encompass Freya! What joy as each word falls one after another like a poem! Like a rhythm in a strangely familiar tune. I love everything about this piece as do I love the workings of your mind. I am so glad that your poignant voice reverberates and is clearly heard and loved through the darkness of this messed up world.

And the red fox sneaking on the white snow is too much cuteness for my heart! 🦊

I think I've fallen in love with your fifth footnote, such a beautiful sentence.

"In the case of my visiting friend, their steps and gaze happened to turn toward me, and now their presence is here among my words, shared with you."