Echoes in both directions

finding voice in between

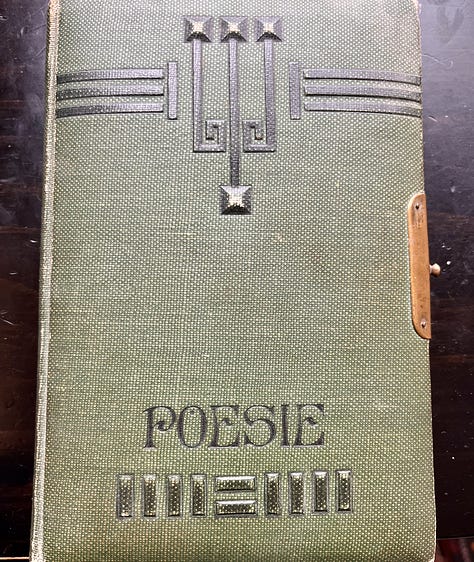

A few years ago my mom gave me a small antique book, art deco styled, with the word Poesie across its cover. It belonged to my great-grandmother, who left Sweden with my grandmother, who was four, her younger sister, and two brothers under ten to sail to New York in 1925. From there, they made their way across the country by train to reunite with her husband, who had left earlier to sail ferries along the Oregon coast with his brother. Their families were shipbuilders who could no longer find a market after decades of industrialization and steamships took hold, and penniless, they left to find something they could do to earn a living along another coast. My great-grandmother never saw her mother, or her homeland, again.

I often think about the forces at play in such stories—how my ancestors exiled themselves to claim a new life in lands that were not theirs, leaving families and homelands behind. What kind of choice did my great-grandmother really have, at home in Sweden with a widowed mother and four young children, waiting for her husband to send for her. Generations that come to a new land and work as part of a nation that displaces those who call these lands home. How the world seems intent on making exiles of everyone—impoverished people crossing the world for opportunities that make other people impoverished. Generations cut off from the language of their ancestors, unable to read the words that were put to paper by their hands. How the world wants us to exile ourselves from who and how we truly are.

I think about it now as my son’s generation can barely read or write cursive. For them, writing involves a screen, and messages to friends are immediate, bite-sized. Technology yet another colonizer—exiling generations from one another as handwritten letters are no longer a part of a material world. I wonder what future generations will make of a world from which they will have no letters.

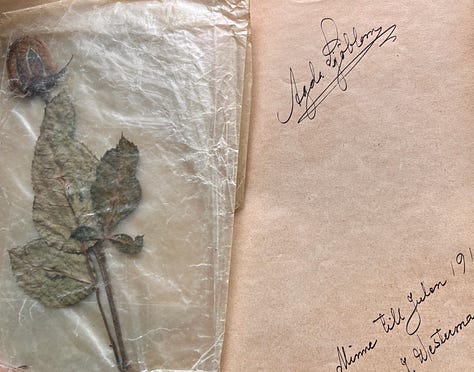

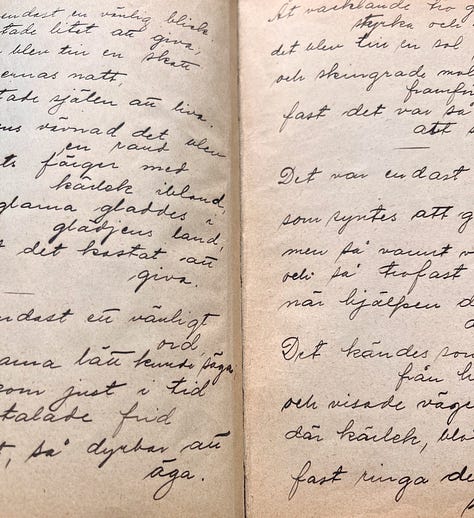

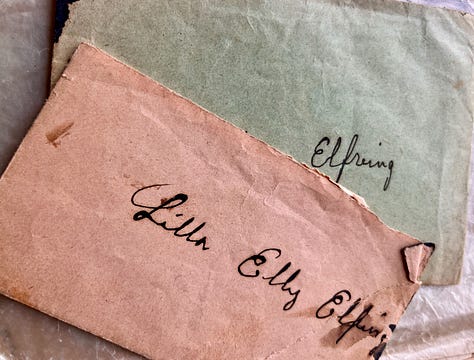

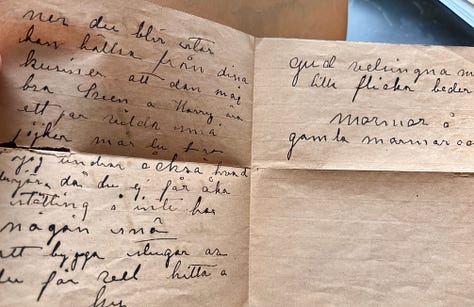

My great-grandmother’s book is filled with delicate scrawls from friends and family. A commonplace book. Many of these entries appear to be small verses—some are signed but some seem to be my great-grandmother’s own lines. Some are also lines she wrote down from favorite writers, like Selma Lägerlof, who won the Nobel Prize in 1909. In addition to the verses, there are two newspaper clippings, taped to the back of the cover that report the deaths of her parents in Sweden. And there are three small notes in envelopes addressed to Lilla Elly, my grandmother—letters from a grandmother she barely knew because of that capricious god, circumstance.

The notes are in Swedish, and there is much I can barely make out, let alone try to read. Through another act of circumstance, I lived in Norway for two years and learned enough Norwegian to get by—and as the language shares much with Swedish, I can read bits and pieces of the writing but not enough for it to cohere.

But because the words are hard to decipher, my eye gets drawn to other aspects of the book—the difference in styles of handwriting, sketches of flowers drawn across the top of a page in pencil, twinflowers drawn on another, above a verse. A pressed rose in a fragile glassine envelope, four-leaf clovers that my great-grandmother noted were found in an Astoria garden the summer she first arrived in Oregon. The uncanny magic of a book that has persisted through time, that remains to be read by a different granddaughter.

In her book Eros the Bittersweet, Anne Carson writes:

I am writing this book because that act astounds me. It is an act in which the mind reaches out from what is present and actual to something else.1

I feel that astonishment as I leaf through the pages of my great-grandmother’s book. A book that links four generations of women, held in the hands of the fifth. Generations of women reaching out from their present to another now, to something (someone) else.

I have no idea if my great-grandmother wrote poetry beyond the verses in this book. But I love to think there is something in my cells of her that is a part of my love of poetry—those invisible forces in all of us, passing through us, through different generations. What traumas, illnesses, joys, loves are mixed into our cells—what do these cells, atoms that make up our bodies know? Where have they been before?

The Swedish poet Edith Södergran wrote in the years just prior to my great-grandmother’s departure from Sweden. I often wonder if she knew of her work.

Södergran lived a brief life after contracting tuberculosis at age sixteen, soon after her father had died of the disease. Despite that she was born in St. Petersburg and then lived in Finland, she was a part of the Swedish-speaking Finnish population—a product of boundaries moving back and forth between different empires, from the lands she lived on being a part of Russia, to becoming part of Finland after disputes with Sweden.

Södergran published four slim volumes of poetry before she died at age 32 in 1923. Poetry that was unlike that published by a Swedish writer of the time, full of fire and conviction in modern, free verse. Each book she published was met with scorn by critics, a response that feels eerily like what Emily Dickinson no doubt would have been subjected to if her poems, as she wrote them, had been published in her lifetime. Critics of Södergran never held back in their disgust, and considered her, at most, “an interesting fool.”2 They asked who she dared to think she was, to think what she wrote was poetry with no rhyme, no meter. That is not poetry.

But there was one woman who recognized the strength of Södergran’s work—author and critic Haga Olsson. After reading Olsson’s positive review, Södergran was over the moon to find connection with another writer. She wrote a letter to Olsson, writing: “Could it really be that I am coming to someone? Could we take each other’s hand?” Despite experiences of malnutrition, disease, and poverty that would not allow the two women to meet briefly more than twice, they wrote to one another for the rest of Södergran’s short life, a correspondence that impacted both women’s work deeply. Olsson later published Edith’s Letters. In Olsson “Edith Södergran found a sister.”3

My sister

you come as a spring breeze over our valleys

The violets in the shade smell of sweet fulfillment.

I want to take you to the forest's loveliest corner:

there, we shall confess to each other how we saw God.

—Edith SödergranIn a letter Södergran wrote to Olsson, she writes:

Surrender yourself to my will, to the sun, to the force of life…Let life fight to the utmost….I want to pour over you my living reserves of strength. I am life, the joyous life.4

In letters and poems, she parallels the work of Dickinson, who also wrote:

I find ecstasy in living; the mere sense of living is joy enough.

And, like Södergran, Dickinson too had a sister to send letters and poems to throughout her life. It was in letters where Dickinson, like Södergran, was able to think alongside the best of all people—an understanding reader. Like Haga Olsson, Dickinson’s friend and sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert Dickinson, recognized Emily’s genius. And, like Södergran, writing letters to people who recognized the strength of her work gave Dickinson life. It was enough for both women to know there was a reader who saw themselves in their work—a reader who was moved by the words each woman wrote on the page.

On foot

I had to walk through the solar systems,

before I found the first thread of my red dress.

Already, I sense myself.

Somewhere in space hangs my heart,

sparks fly from it, shaking the air,

to other reckless hearts.

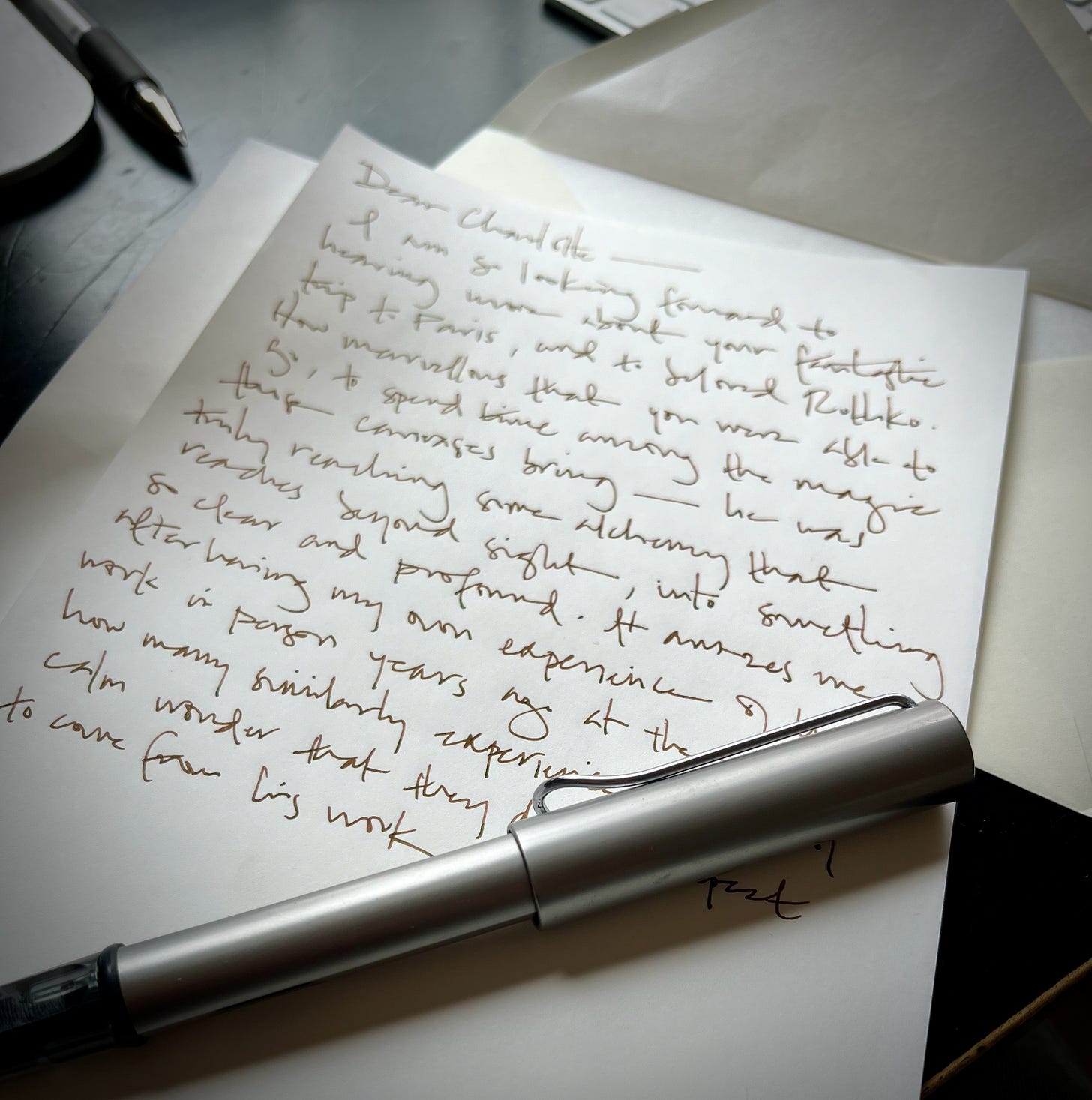

—Edith SödergranI’ve been writing letters to a few of you,5 and have been happily reminded of how writing to a specific someone involves thought, reflection, time. Writing to someone invokes a sense of presence—you write about what you know of that person, even if only gleaned from comments or writing you have shared. I think over those details as I write. Writing a letter becomes an act of focus, holding the recipient in your thoughts—an act of attention toward others.

Writing is such a solitary act—and yet there is a sense of presence in knowing when we put words on a page they are something that can be read, for some other breath to come and make them real again in a different moment. When I pick up my great-grandmother’s commonplace book, I wonder if she had any sense that she was, in a way, also writing to a daughter, granddaughter, great-granddaughter. Spending time with the pages is like returning to a room I now get to know that I wouldn’t otherwise have access to—a looping of past-future-now. Spending time with it, I in turn offer time and thought for ancestors in a way that I wouldn’t otherwise know how to make time for. It’s a curious thing, these words, ephemera—how they can hold meaning across time and generations. As Gaston Bachelard writes:

…we are echoes in both directions, finding voice in between6

Katchadourian, Stina. 1981. “Introduction,” in Södergran, Edith. Love & Solitude: Selected Poems 1916-1923. Translated by Stina Katchadourian. Fjord Press, San Francisco. p. 8

Ibid.

Ibid.

with more to come soon to those who have not yet received anything in the mail as yet—they should be out this week!

Södergran astonishes me! "I had to walk through the solar systems, / before I found the first thread of my red dress." Just wow. Thank you for this beautiful story!

This is beautiful, Freya, and made me cry. I chatted with a taxi driver last week about the fact that nearly all of us in Australia are migrants, whether first gen or fifth gen or somewhere in between. We have no written remains of my father’s family who came from Scotland in 1913. And precious little of my mother’s ancestor who was transported in the 1830s.