I’ve thought about the word labor quite a bit over the course of my career. Labor as a worker, as a task of care, a task of upkeep, labor as exertion, labor in childbirth. Labor, meaning to toil, suffer—from Old French to work, toil; struggle, have difficulty; be busy; plow land, from Latin laborare, to work, endeavor, take pains, exert oneself; produce by toil; suffer, be afflicted; be in distress or difficulty.

The words of difficulty, struggle, with a repeated inference of suffering, pain, to be in distress, difficulty. Odd that a word used to reference work—how we spend so much of our daily life, whether paid or not—is so laden with a sense of struggle, to produce by toil. If one labors without toil, is it still labor?

Labor wasn’t a word applied to childbirth until the 1590s, when it was introduced from the latin in Spenser’s Epithalamion. I have yet to find a reference that indicates what word or root was used to describe the process of childbirth prior to that use in print—pains? That word also shares meaning with labor—c. 1300, to exert or strain oneself, strive; endeavor. To endeavor, exert oneself [strive], to take pains [exert or strain oneself]. Is it odd that the action we all must take as humans to work for a living, to reproduce the next generation, the daily upkeep of our homes, children, and our own lives—that the word we find for it refers only to exertion, strain, difficulty, suffering? If we labor without pain and suffering, is it considered real work? Is that the only way work can be done?

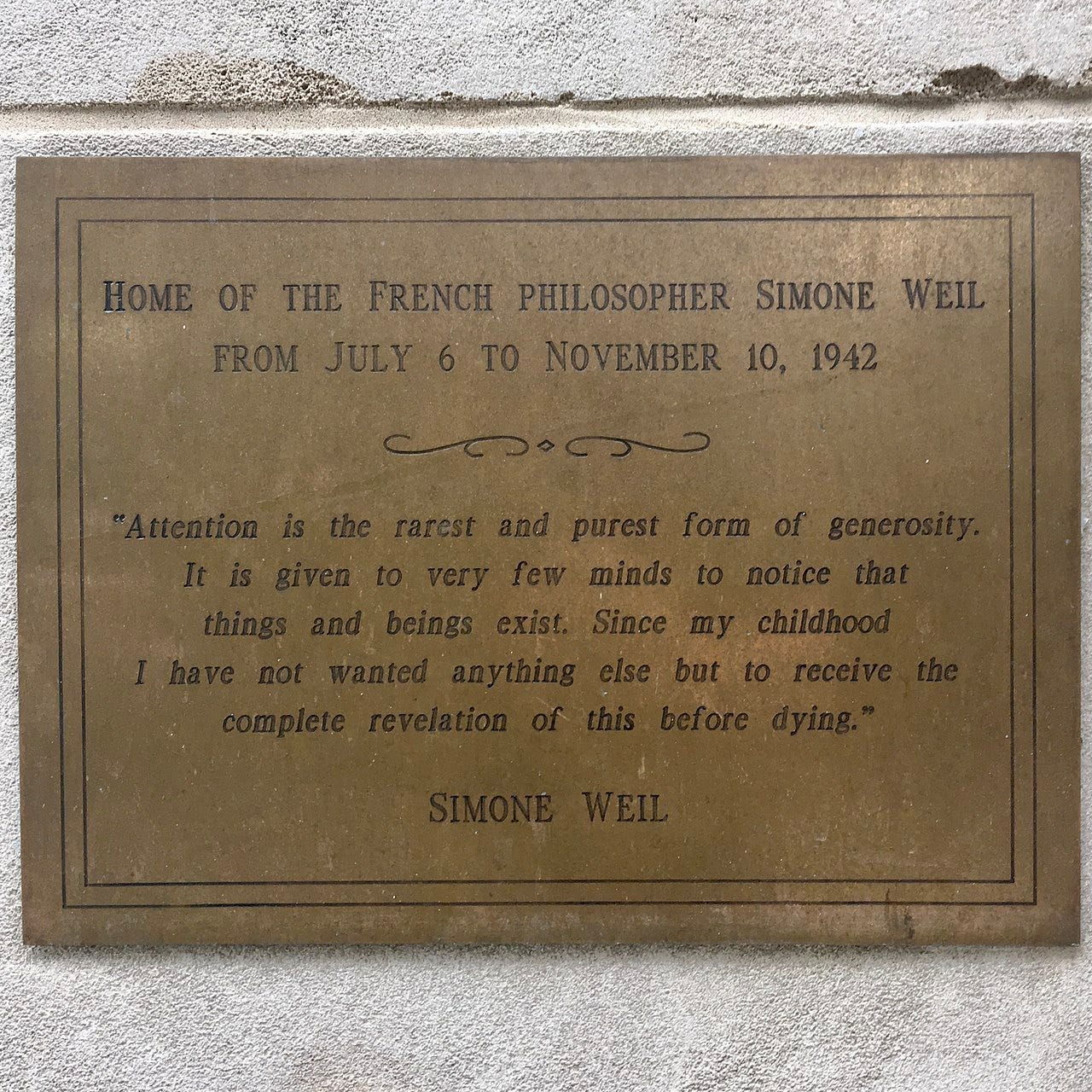

To be afflicted particularly catches my eye, as this is a main concept in Simone Weil’s work—le malheur in French—which she first truly understood when she worked alongside other women in a factory job for three years.

Weil believed that le malheur resulted not only from physical suffering of factory work, but more devastatingly, from the psychological degradation experienced by herself and fellow workers. Robert Zaretsky writes of Weil’s experience:

Ground down by relentless and repetitive physical labor, workers were also shorn of human dignity. Harried by time clocks and hounded by foremen, serving a machine and severed from a real purpose, the workers were quite simply unable to think at all, much less think about resistance or rebellion. Horrified, Weil realized that the factory ‘makes me forget my real reasons for spending time in the factory.’”

What astonished Weil most was how little focus the work required, and yet it was enough that it eroded any capacity for attention—to be starved of attention for a world that necessitated it. Exhausted and exploited—with women who had to bring their children along to work, which Weil discovered in a break room where a fellow worker’s young boy was sitting—the factory work stretched employees within a hierarchy and rote busy-ness—to exert and produce by toil. Weil realized and saw that this system of work made zombies of staff, who had no way to give any attention to the world around them—an attention that is an act of care, the only way to see a way towards justice. Weil wrote:

Human history is simply the history of the servitude which makes men—oppressors and oppressed alike—the playthings of the instruments of domination they themselves have manufactured.

For Weil, affliction was the call to attention of how universal it is that life as we know it—for men as well as women, oppressor as well as oppressed—can evaporate before our eyes. Affliction is the great neutralizer that creates the universal human condition. Weil believed that in order to acknowledge the reality of affliction

means saying to oneself: ‘I may lose at any moment, through the play of circumstances over which I’ve no control, anything whatsoever I possess, including those things that are so intimately mine that I consider them as myself.’

For Weil, to hear the cry of the afflicted is the basis of all justice.

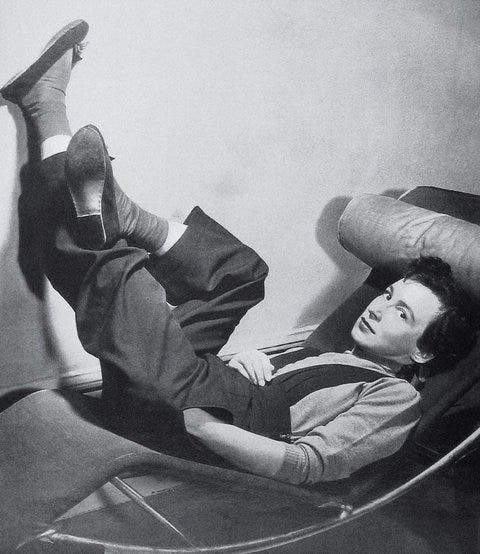

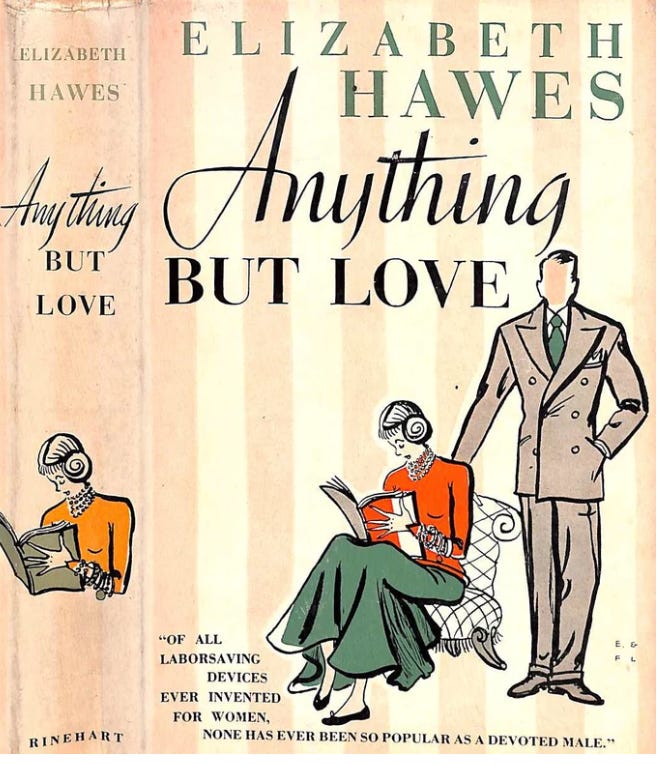

There was another firebrand of a woman who was writing, creating, working alongside other women in factories around the same time as Weil. Elizabeth Hawes was a fashion designer and writer, a graduate of Vassar in 1925 with a degree in Economics, with interests in socialism. After graduating, she was determined to move to Paris to learn fashion design, and picked up reporting gigs to support the move, which ultimately became a regular column for The New Yorker, where she wrote under the pen name “Parisite.”

While Hawes returned to New York to create her own dress design business, what she learned and observed in Paris left her cynical and ambivalent about the production of luxury haute cotoure design, and she became far more interested in clothes that allowed people to feel comfortable and free. She was an advocate of women wearing men’s clothes and men wearing skirts, of being nude if/when that’s most comfortable. She created ready-to-wear styles that were more accessible and freeing for consumers. She also made some beautiful designs that were akin to Coco Chanel, but were created ten years prior to Chanel’s famous silhouettes.

Hawes’ first book, Fashion is Spinach, is a sort of manifesto that rants against the fashion industry, pointing out the ways it manipulates consumers, particularly women, being admonished to throw out old clothes and spend more and more, in thrall to new designs:

Style gives you the fundamental feeling of a certain period in history. Style doesn't change every month or every year. Fashion is that horrid little man with an evil eye who tells you that last winter's coat may be in perfect physical condition, but you can't wear it.

What I love about Hawes is her quick wit coupled with her seriousness in changing exploitative systems. She approached fashion as a sociological phenomenon, examining the ways in which fashion can liberate women and men from strictures that confine them—literally and metaphorically—and the ways that it can also serve more people, rather than only the rich. Alice Gregory writes of Hawes,

She wrote about [fashion’s] economics, culture and ethics; she maintained, with barely a wink, that being perfectly dressed ‘contributes directly to that personal peace which religion is ultimately supposed to bestow’.

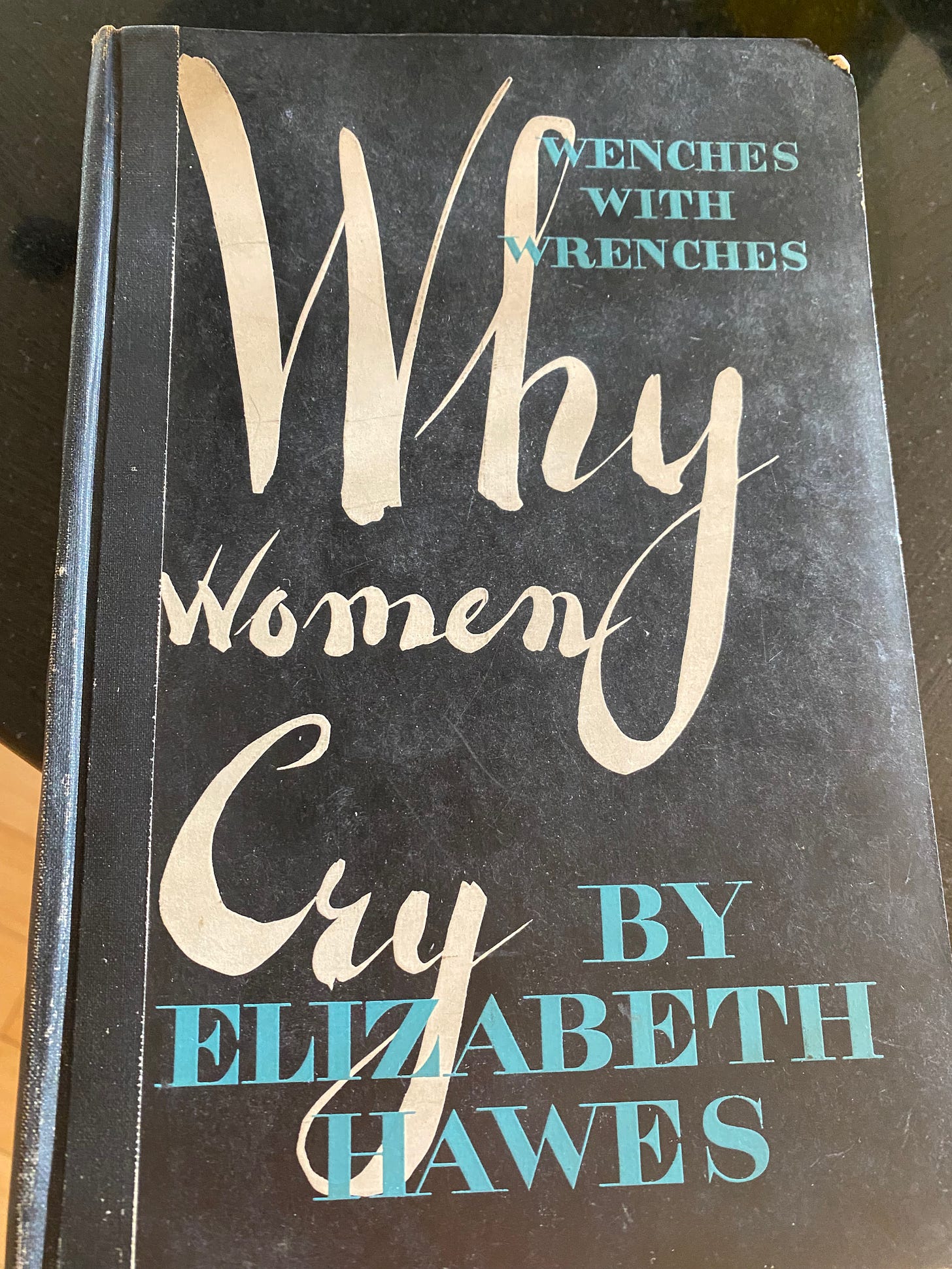

Hawes’ book Fashion is Spinach is a stand-out, and that it’s not more widely known is shameful. But what I love even more is Why Women Cry (or Wenches with Wrenches). Written in 1943, I was able to find a more inexpensive copy after searching for some time—so much of her work is out of print. I have it prominently displayed in my bookcase because it feels so apt for all that is happening around us, this backlash to whatever white men in power seem to think is threatening them, the efforts to control pregnant people’s bodies and the sexuality of every goddammed person. Elizabeth Hawes would be angry as hell, as we all are.

I want more of her books to display because the titles are such obvious running commentaries about the misogyny and inequality of society: Hurry Up Please It’s Time. Men Can Take It. Why Women Cry. Why Is a Dress? But Say It Politely. Anything But Love: A Complete Digest of the Rules for Feminine Behavior from Birth to Death; Given Out in Print, on Film, and Over the Air; Read, Seen, Listened to Monthly by Some 340,000,000 American Women. It’s Still Spinach. Hawes was bold, sarcastic, and serious all at once.

Hawes grew more and more interested in new political ideas of socialism and communism, before the outbreak of World War II. As war broke out, she closed her shop, believing she could do more for society and the war effort than design clothing, and went to work in a munitions factory, and then moved to Detroit to work in the United Auto Workers Union after the war, particularly addressing working conditions for women. She advocated for on-site childcare—being appalled at the lack of care available to women workers that Weil also witnessed in her factory experience. She also began writing for a left-wing paper as well as the Detroit Free Press. Most of that work of that period would later become Why Women Cry.

Hawes’ advocacy is right on point for the oh-so-many discussions we have read over the past years, about the burden placed on mothers, about women having to leave the workforce in droves to provide care during the pandemic—and the general untenable situation of women who still end up doing the majority of house and care work while holding down a full-time job where they are criticized for not showing greater commitment to their jobs by being distracted with parenting.

What follows is a bit long, but it’s so telling. In Why Women Cry, Hawes writes of a friend who has worked for months to get hot lunches in the public school her children attend and for arranged after-school care activities. Hawes’ describes a discussion of this friend and her husband:

Amanda walked in to her husband one night and she said, “I am going to leave you and you can take care of the children.” “What?” he said. “I’m sick of it all,” she said. “I’m going back to work—any old work. You try and figure out how the children are to keep busy and not just gamble all the time after school. Let Mrs. Jones’s husband try and figure out how she’s ever to have a moment to breathe, with a child two and another four and another seven. Let HIM start learning about nursery schools for a change.” “What’s a nursery school?” Amanda’s husband asked disinterestedly. “Something your next wife is going to start wanting when her first child gets to be two. Join the National Association for Nursery Education..and find out for yourself.”

Ha! The next chapter, titled “It Could Happen Here” begins this way:

A few months later Amanda’s husband arrived home in a very bad mood. He’d come out on the train with Mr. Jones who said Mrs. Jones was driving him mad about something called Nursery Schools. He had tried to convince Mr. Jones his wife was right, and, he told Amanda, Jones was just a stupid fool who didn’t even care to find out what was best for his children, much less how many hours a day his wife spent in the kitchen. “He won’t even read a book,” Amanda’s husband said.

Apparently, Amanda had some success in getting her husband to read up on childcare and parenting.

Amanda and her husband then begin to reminisce about a vacation in a hotel with a central dining room and dream about community living:

“I’ve been thinking. If things were built properly in the country you could have a group of houses like that. There’d be the central building with the dining room, probably a cafeteria, then you could go over and haul your own meals back if you wanted to eat alone. Remember everything was always hot or cold, all the right containers for carting it around and keeping it? And the rooms just got cleaned up by the servants,” “You wouldn’t have to have all those servants,” Amanda said, “if the houses were built and furnished for self-cleaning. Anyway, there won’t be all those servants. But people in places like that are quite well-paid and good at their jobs. If you hired them like human beings, for certain hours and decent wages and all, it would be as good as any other job. Lots of people like to cook and most of the dirty work could be done by machines, dishwashing and all—no old-fashioned cleaning.” “I suppose it would be rather expensive, maybe,” Amanda’s husband said…. “It wouldn’t matter so much if things were just efficiently arranged,” Amanda said. “It’s much cheaper to buy food in bulk, and in a plan like yours it could be sold at cost, as it were, sort of like the Government Restaurants they set up for the workers in England. The houses in the group could be different sizes. Aren’t we fools to live the way we all do?”

Aren’t we fools indeed.

They continue to dream of this communal arrangement, adding a place for central child care. And then Amanda’s husband goes on to to quote a parenting book he read that had been on her nightstand and amazed, she remarks

“You’d better not go at this too hard,…or you might get indigestion….Gosh, if there were really such a place to live, then I could have a job again. I’d rather you know. The kids can be okay without me being around their necks all the time.” “I wish you’d get another job just as soon as you can,” Amanda’s husband said. “You are getting to look a little, a little,…” “Like a housewife?” “Well, you look much better since you got all wound up in this school business…”“Why don’t you make a drink?” Amanda suggested. “I don’t know if that’s recommended for prospective mothers by the best authorities,” he said. “Everyone can’t be perfect all the time,” Amanda smiled. “That obstetrician I tried this time told me I mustn’t drink any alcohol at all. Why, I told him that was my only pleasure when I was pregnant.!” “Darling, really…” “I suppose the day will come when it isn’t shocking to say that being pregnant is just an awful bore,” Amanda said. “It’s what you have to be to have children, so that’s that. I wish I could have a regular outside job now. It would make the time pass more quickly.” “When we get the housing project, you’ll be able to,” said Amanda’s husband. “Meanwhile, I will cheer you up with some alcohol. Maybe when we get the project we won't need so much of that either!”

This was a dream conversation in 1943. Is it eerie, or collective social denial and erasure, that the same issues, same burdens, same concerns, same lack of awareness, same inequality are all still with us—that the same type of conversations still get treated as if it is anathema to imagine a world without nuclear families, of living like a community rather than individuals married to another individual having individual children in our individual homes?

Needless to say, the FBI had a large file on Hawes for some time, but she was never affiliated with communist organizing. She simply wanted a fairer world for women and men, for racial justice, for labor justice. She argued for dress reform and believed women should always wear trousers because they allow for movement (for pete’s sake). She designed the outdoor uniform for the red cross during the war. She married her second husband in jeans. A woman after my own heart.

Of course women like Hawes are quickly forgotten, even during their own lifetime. She returned to New York for a retrospective of her work in 1967, but there was little notice. She died in the Chelsea Hotel in 1970, from cirrhosis of the liver—alcohol being too necessary still, in a world that demanded that women and men live and labor in such inequality and exploitation.

It’s a stretch at first to look at both Weil and Hawes and find a connection—one a brilliant philosopher mystic who was so dedicated to the plight of the worker that she suffered physically with illness and ended up starving herself to death in solidarity with the rations that she believed the German-occupied French were afforded; the other a brilliant designer and writer who saw through the manipulation of industry and worked to advocate for the equality of women and men, of workers and access to community support. But I was struck reading their work at how they both clear-sightedly felt a deep need to understand what society was doing to those who labored, and to advocate for justice. And while different in their approach, both women wrote of the abuses of the factory—which they both felt a need to personally experience—and to write of what an industrialized, systematized world is doing to those who labor within and under it.

Reading them both, it’s maddening to think that we are still here, that the backlash we’re seeing to so many egalitarian ideals are being squashed once again. But then I’m also inspired by the rise of unions at Starbucks, at Museums1, at organizations across the country, of a recognition that work as it has been made is broken. The work that Weil and Hawes both saw and were horrified by in factories and in industry, and their work to call attention to the need for change, at least continues.

Women like Weil and Hawes are so often called ‘ahead of their time,’ writing about issues that are being discussed now—as if the present had invented or has some corner market on ideas that break the victorian ideals and binaries so many want to cling to. A different way to move in society, a different way to support others in society. But Weil and Hawes were exactly of their time. The past is not some dark hole where progressive ideas were exceptional forecasts of a time to come. What’s enraging is that the ideas and social change that Hawes and Weil advocated for are still ahead of our time.

and, as some readers know, I have written about my own experience in working at a toxic museum, and how so many museums are structured to thrive on out-of-touch boards, toxic leaders, and exploited staff. Let alone operate under wholly colonial and racist frameworks. But I digress…

Once again, you open my eyes and challenge my mind! I will be ruminating on this for quite some time, and, I am sure, more insight will emerge! Reading Epithalamion was another window for me to look into the world of poetry few of us indulge in. It reminds me of a symphony as it unfolds its story in music. Well done!

Wow! This article is exemplary. The parallels you drew from the work of two very different writers, are mind blowing. I am deeply influenced by Weil’s work, but never heard of Hawes before. Thank you for sharing this great piece Freya!