Malleus Maleficarum, The Hammer of Witches

Folktales and witch trials tell much about a post-Roe world

Hello everyone, and thank you so much for reading. This is the weekly(ish) edition of The Ariadne Archive, which you can read more about here.

I wanted to take a moment to thank you all—old and new subscribers alike—who have all supported this newsletter. There are many more of you now than even a few months ago, and I’m so grateful for your time reading my work!

I started this newsletter almost three years ago, after leaving a very toxic work situation. Writing is what has always given me solace and meaning, and I wanted to return to it full-time—at a time when the whole world was also shutting down and rethinking the toxic structures we are too often told to follow.

I’ve been an archaeologist, curator, and writer interested in obscure histories and marginalized stories—particularly of women writers—and decided to loosely frame my work around those threads. A way to shine some light on stories and voices that are too often obscured and deliberately hidden. I love to do this work and it means so much to me to do it in company with readers and fellow writers who see the value in it as I do.

All of this is to say I’m so grateful you are here! These essays take up to thirty hours of research and writing, and I know I won’t be able to continue doing it if I have to seek out more traditional streams of income. So to my paid subscribers, particularly—thank you for contributing your financial support. I am so incredibly grateful.

I try to support and pay the writers I read as much as I can, but I know it’s a hard thing to do. It’s why I want to make as much content free as possible. I want as many others as possible to know of these stories, while also figuring out a sustainable income for my work. I haven’t reached that goal yet, so if you can upgrade to become a paid subscriber, I will continue to work hard to make it valuable for you as a reader.

Right now, paid subscribers have access to the full archive of essays. But as many new subscribers are here, and it’s that witchy time of year, I wanted to take the paywall off and share one of my favorite essays. I posted it a little over a year ago, as we tried to absorb the news of Roe v. Wade being overturned, and the coincident threads of a time when women were accused of witchcraft felt alarmingly close.

When I lived in Norway, many years ago, we lived near the sea—so near in fact that the house was buffeted against the tide by just a dirt road. You could throw rocks from the windows of our room and hit the water at high tide.

It’s a favorite memory, living in that place alongside the inlet—the Trondheim fjord, to be exact, although it lacked the characteristic chasms of what is often thought of as a fjord. I spent a lot of time on my own in that house and became familiar with the sounds and patterns, the animals that would come and go at different seasons.

I’ve always been fascinated by sea mammals, particularly—the magic of being safe and unburdened by gravity or cold, breathing air but living in water. I’d sometimes watch the tides and wonder what it would feel like to become a seal.

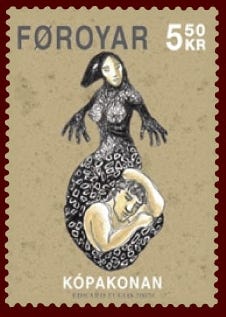

It’s not an unusual thought for that Norwegian coast, or for the Scottish coasts of Orkney and Shetland, the Faroes, Iceland. Those places have stories of selkies—seals that can turn into women and men, moving between land and sea—but stories of women selkies are more common. Several tales describe several selkie women coming ashore in the moonlight to slip off their sealskin and stretch out on rocks, before donning their skins and returning to the sea.

The main narrative of the most common story is of the selkie wife: a selkie woman becomes unknowingly discovered by a fisherman when she is in human form. He instantly falls in love with her and steals her skin so that she will have to stay with him since, without it, she can no longer return to the sea. She agrees to his care and lives with him as his wife, becoming an ideal wife and mother, but always somewhat distant and otherworldly. She’s often eyed with suspicion by the village or community, singing songs in an unrecognized language.

Finally one day her daughter comes across a chest in the attic or under an eave, where the mother’s sealskin has been locked away. Instantly the selkie wife takes the skin, and says goodbye to her children, but cannot stay any longer. She must return to the sea. In some stories, she watches over her children from the shore, who, as half-selkie themselves, can still understand her selkie speech.

These stories are so pervasive in the Orkneys, particularly, that there are stories of families with inherited traits of webbed feet, proof of a selkie ancestor. And while seal oil, fur, and meat are an important resource for the treeless northern islands and coastlines in Orkney and Shetland, there were also stories of bad luck associated with killing seals—to avoid revenge selkie magic, or the inadvertent killing of a relative.

I’ve always liked selkie stories because they remove some of the glamour and kitsch of mermaids, and replace it with the magical reality of animal. The stories also speak to the experience of exile, or of those made to fit into a world that was not made for them—like the selkie wife—exiled, obedient under coercion, longing to be able to live in her true skin.

I read a while back that a woman’s first trauma happens when she becomes a teenager. It has the ring of truth when you consider what it means to be a woman in a patriarchal society.

As teens, girls are taught that at some point their bodies will betray them, become visible. Teen girls quickly become schooled in vigilance—to be alert for when our bodies might begin to bleed or become conspicuous. Girls learn that a woman’s body is something painful, messy, or shamefully obvious—something that needs to be bound, managed, hidden—to disguise and conceal the very thing our bodies are becoming. As teens, girls learn quickly how a woman’s body draws attention—unasked for, unwanted. They learn that the gaze of male teachers, men, and boys starts to differ. Teen girls are taught to please and care for the comfort of others before their own—and so they learn how to deflect, to be demure, to deny, to try to stave off attention from men. And that the blood that arrives each month—that can ultimately give life—can also be the source of their own death. It is a traumatic experience—that one’s body can also be a source of danger.

And then—once women are no longer deemed pleasing to look at, they become invisible—still exiled from being whole. Selkie wives who have lost their skin, identity, claim to agency. Women are consigned to the realms between—between private and public, between trying to be fully human in a man’s world, or fully human in a woman’s. Ghosts without skin, revenant, haunting with our desire to move in our own skin, our own bodies.

Women writers have known this—it’s why so much of nineteenth-century women writers chose to write stories of gothic horror. Rosemary Jackson, echoes the feeling of displacement and need to hide that women can feel, writing of those gothic women writers:

Displaced from their society and history, dislocated from their bodies, minds, and marriages, [women] move into another realm, in between things, to a kind of no-man’s land. Feeling that they do not belong socially, they come to occupy the ultimate non-social, asocial position—that of the specter, madwoman, or ghost.

With the events of this week—the damning, arrogant, dismissive court opinion of Justice Alito—I keep returning to that description of those women writers of the Gothic—of how little has apparently changed. Or perhaps more accurately, how close we are to joining their ranks more explicitly. But really, I’m not sure that for the majority of the women of this world, it has changed in centuries. Because the overturning of Roe Vs. Wade by a white man’s opinion is simply a codification of the systemic misogyny faced in patriarchy: that a woman’s body is merely an empty vessel, a machine, vacated by spirit and ownership of identity and will.

To be made a ghost—or to unabashedly mix several metaphors—a selkie walking the shore, missing her stolen skin.

Or a witch.

In the draft opinion overturning abortion rights, Alito chooses to support his argument with reference to precedents that are “deeply rooted in history”—despite also including myriad arguments as to why precedent must be overturned at times like this. It’s a baffling argument—but even more baffling is how the legal system continues to perpetuate legal doctrines that arose and were created by white English men in a time when similar precedents were being cited to justify enslavement and colonization,1and when witchcraft accusations ran rampant. These precedents are still being used—up to six hundred years later and longer—to keep society confined to the mores of a white Christian nationalist patriarchy.

Alito cites three legal tracts specifically, written by Matthew Hale (17th century), Edward Coke (16th century), and Willam Blackstone (18th century).

Matthew Hale lived in England from 1609-1676. Among other writings and legal acts, he sought to extend capital punishment to those as young as fourteen—at a time when capital punishment involved, in many cases, being hung, drawn, and quartered. He believed that marital rape doesn’t exist, because (as his later colleague William Blackstone asserts, below) because upon marriage, a woman is the property of the husband and has no rights; as she moves from her father to her husband’s house, she is under the control of men. And in marriage, husband and wife are one person, and the one is the husband. Therefore, Hale argued, there is no way that rape can be perpetrated by a husband on a body that does not exist except as his own. Hale’s beliefs in this have been so influential in the courts and legal system that they were only dismantled in 1991 in England, and not until 1993 in the United States.

In 1662, Hale was also involved in one of the most notorious English witchcraft trials, where, as Lord Chief Justice of the Crown, he sentenced two women to death. The case was extremely influential across future witchcraft trials and convictions, and was used as a model for, and was referenced in, the Salem witch trials. G. Geis, writing in the British Journal of Law and Society, ties Hale's opinions on witchcraft directly to his writings on marital rape—an appalling implication confirming a belief in women as ghosts, of bodies that are not due any rights. Hale famously used the circular argument—without irony—that the existence of laws against witches is proof that witches exist.

Edward Coke (1552 - 1634), living a century before Hale, also had a hand in witchcraft trials. While he influenced the upholding ideals of habeas corpus and the right to silence, in 1604 Coke broadened the Witchcraft Act to bring the death penalty without “benefit of clergy to anyone who invoked evil spirits or communed with familiar spirits.” This expansion of the law effectively served to directly take those accused to execution without further delay—or chance of opposition or appeal. This was the statute that became enforced with fervor by the self-styled “Witchfinder General,” Matthew Hopkins, who accused and brought over 100 alleged witches to trial between the years 1644 and 1646, and with his colleague John Stearne, sent more accused people to be executed than all other so-called “witch-hunters” in the previous 160 years.

Then there is Alito’s reference to William Blackstone (17232 - 1780). Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England is a lay summary of the common laws of England up to the 18th century. Blackstone’s writings have in fact influenced the framework and structure of the American legal code more than the legal codes of the United Kingdom.

Among other famous quotes cited as precedent in court cases is Blackstone’s definition of marriage and coverture laws, essentially affirming the conclusion drawn by Matthew Hale a century earlier with regard to views on marital rape and the lack of rights of a married woman:

By marriage the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs ever thing; and is therefore called in our law-French a femme-covert; is said to be covert-baron, or under the protection and influence of her husband, her baron, or lord; and her condition during her marriage is called her coverture….

It wasn’t until 1966 that a Supreme Court ruling declared coverture laws an “archaic remnant of a primitive caste system,” intent on supporting male privilege and female subjugation. But it wasn’t until 1981 that the Supreme Court effectively revoked coverture frameworks, ruling that the practice of male rule in marriage was unconstitutional (Kirchberg v. Feenstra, 450 US 455).

When I first began writing about witches earlier last year, I was thinking about what it did to women’s psyche, of the trauma of seeing other women be accused and executed for healing, for wisdom, for miscarriage, for side-eye, for anger, for being visible when she should not be—most often when she is poor, old, and a widow. When women are without ‘protection’ from men. How often the law does not like those who are already traumatized, beaten, and coerced by the system. How old these attacks on women’s personhood actually are.

When I read the draft opinion this week, I couldn’t stop thinking of ghosts, of walking the shoreline, calling to my ancestor sisters in a language that they can hear from beneath the water, calling to all of them for help in reclaiming our skins. The control of anyone’s body has been constitutionally averred for over a century.2 The fact that such an amendment was needed, took far too long, and was the cause of too much tragedy, death, and forced labor by bodies whose humanity was grossly denied, is infuriating to consider.

How in the world can such an opinion, based on precedents written by those who also executed women for witchcraft, be written in sanguine, assured confidence in 2022? 3 To control half the population’s bodies, to enforce the production of labor and impose the impoverishment of that labor for exploitation (because the most vulnerable will be most affected, and the children that are forced into a life unsupported by society are in turn the most vulnerable to exploitation) so that this country can continue to remain a coercive and falsely white nationalist Christian nation…

I want to use the gothic power of our women writer ancestors. I want to haunt these white male politicians and legal theorists asses out of the chairs of history and minority rule and burn this ideology to the ground. It has no place for the country and society that we so long to live in.

I keep thinking about what epithets Jane Anger would write in response to Alito’s opinion…4

Such as citing the Doctrine of Discovery as precedent—which is based on a 1494 European law that states only non-Christian lands can be colonized and was used to justify the seizure of Indigenous lands for centuries.

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Some in the media claim that Alito will scrub his invocation of Coke from the final draft, but make no reference to his use of Hale and Blackstone as precedent.

“Fie on the falsehood of men, whose minds go oft a-madding and whose tongues cannot so soon be wagging but straight they fall a-railing. Was there ever any so abused, so slandered, so railed upon, or so wickedly handled undeservedly, as are we women? Will the gods permit it, the goddesses stay their punishing judgments, and we ourselves not pursue their undoings for such devilish practices? O Paul’s steeple and Charing Cross!”

I know I'm supposed to be about nonviolence and all that, but I would love to see Alito's head on a pole outside someone's stockade. I mean, if we are going to get medieval, let's get medieval.

"I was thinking about what it did to women’s psyche, of the trauma of seeing other women be accused and executed for healing, for wisdom, for miscarriage, for side-eye, for anger, for being visible when she should not be—most often when she is poor, old, and a widow." - This resonates deep within me. I have felt a close connection to the Witch or old crone archetype because even if burning at stake has become obsolete, the witch trials have never ended. Like the abortion law you were talking about, women all around the world are still facing equivalent violation of human rights. Check this out :

"Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) considers the forced sex in marriages as a crime only when the wife is below age 15. Thus, marital rape is not a criminal offense under the IPC. "

Marital rape is still legal in India.