Print wars and the origins of free speech

hint: gender, race, productivity, and profit

I was recently reading an article by Kate Manne, who writesMore to Hate, with regard to the weaponization of free speech. And in the wake of substack owners equivocating on moderating hate speech on its new Notes feed—in the name of protecting free speech—I can’t stop thinking about the discussions I’ve read around those concerns as Notes came online1. Within days of launching, a gross anti-semitic meme was looping in people’s feeds. Both white and black women were being harassed and attacked for writing about why moderation is necessary, and asking for substack to take a position on moderation. Only to hear crickets.

By not addressing regulations on the moderation of hate speech, in the name of free speech, the media landscape always seems to descend into ceding space that was never agreed to be annexed. It’s a mind land grab. Claims of free speech have become a dog-whistle to mollify a minority who thrives in being offensive, amplifying the voices that do harm. It allows for the tyranny of the minority.

We are told to simply block, mute, look away, to not read what we find offensive. But it’s there, and it is colonizing the minds and bodies of people we all have to live with somehow. Minds that are open to hate rhetoric, and replicate it. It feeds fire, it persuades, it allows, it insinuates. It hurts. And those who are marginalized face the weary tide of it all, to have to do battle yet again and again and again. On their own.

Does free speech matter if no one listens? I’ve long believed in the rights of free speech but I also see the increasing damage of holding onto it dogmatically. Absolutes don’t exist, no matter how hard we try to create or uphold them.

How free speech is now talked about echoes the rhetoric around guns and vaccines. It is all a tyranny of one person’s right to put others—always seemingly those without power—at insane, and in many cases certain, risk. With both mental and physical harm. Free speech has become a dare—of how much can be said, just like it’s become a dare to see how many automatic weapons one family can put into its christmas card (!). Free speech has become the dare of not being open to other opinions, the dare of not being inclusive, the dare of not caring (a la that first lady’s infamous coat: I don’t care. Do you?). The dare of not having empathy. The dare of being the most obnoxious and crudest in the room.

Free speech has become Brett Kavanaugh yelling and whining through his congressional hearing, decrying anyone (i.e., women whom he assaulted) who would dare question his entitlement, while Ketanji Brown Jackson has to show immeasurable, silent grace while suffering racist attacks. It has become radio personalities who capitalize on conspiracy theories that devastate families who have already been through the absolute worst-case scenario, causing unspeakable harm for the grossest of profits.

Claims of free speech are weaponized. Proponents of free speech in these cases—the majority of which are, surprise, white men—shut down those who don’t like what they say by claiming defamation and complaints of being canceled (so tired of this term). They play the victim to avoid any consequences for the harm they inflict, and cry foul of being held responsible for anyone they victimize.

Unsurprisingly, when women seek to claim the landscape of free speech they are most often dismissed. This of course is nothing new. It was happening in the eighteenth century (and before), when print culture became more democratized with inexpensive periodicals and pamphlets, opening up the possibility of authorship beyond (primarily) elite (white men). Not unlike the proliferation of social media in the last decade. Many elite men—the majority of authors published up until that time—unsurprisingly did not like the access periodicals gave to writers who were now being published, and often claimed defamation—particularly when it was women who did the writing.

Delarivier Manley (1674-1724) and Eliza Haywood (1693-1756) knew this well. Despite being some of the most prolific writers of the period publishing in English, with subversive feminism, their works became largely forgotten. Haywood, particularly, only began to be studied critically in the 1990s.

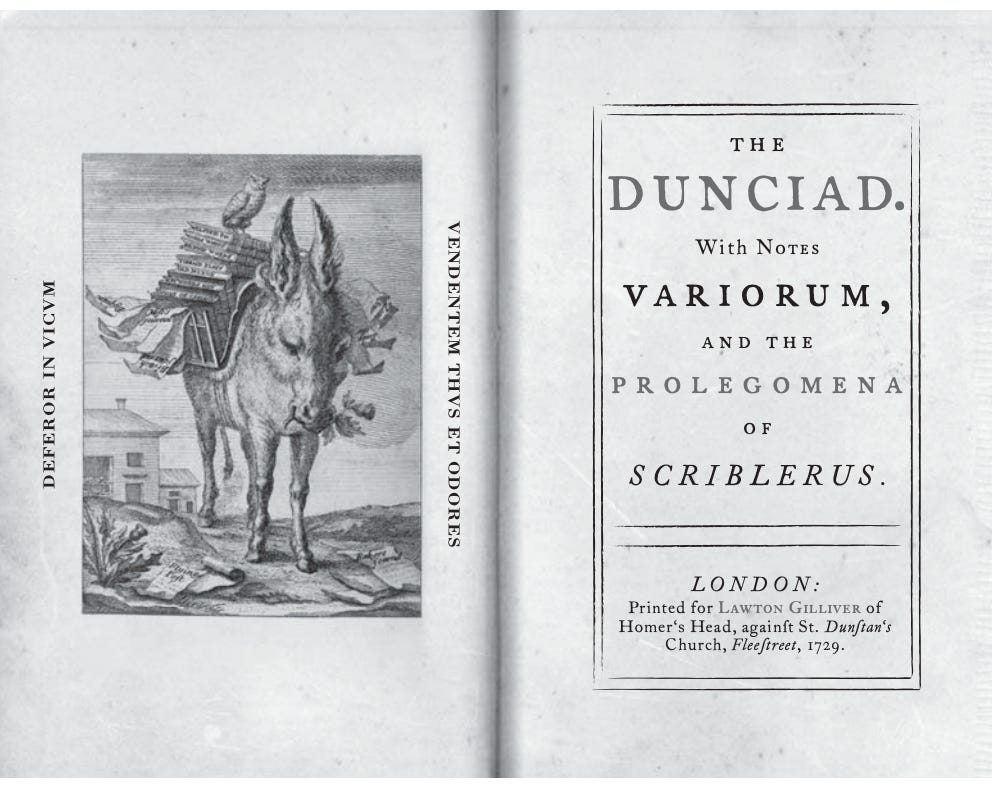

And both women were not at all unfamiliar with the derision of men who would claim all the ink, and yell epithets at women who spoke publicly. Like so many of their contemporary counterparts, and as the great lyz Lenz would say, men yelled at them. Alexander Pope famously ridiculed Haywood in the Dunciad, a trolling that was largely how her legacy was remembered, despite being one of the most prolific and popular writers of her day. The fact that these women’s work was effectively silenced by the men who determined what is ‘canon,’ who dismissed so much of women’s role in creating literary forms and ideas, is a telling legacy of misogyny’s grip on free speech.

Delarivier Manley was an early writer of political propaganda. She earned a living through writing and acting, publishing six volumes of political allegory, political pamphlets, as well as issues of the Tory Examiner. Her novel The New Atlantis caused a scandal by satirizing the sexual affairs of many prominent courtiers, courtesans, politicians, and aristocrats—free speech that cut too close to the bone for the men in power she exposed. She and her publisher were promptly arrested for slander when it came out. She remained in prison for over four months.

Later, in 1709, Manley began the first women-focused periodical. Naming it The Female Tatler, she aspired to set the context for the periodical by alluding to the widely respected, male-written The Tatler. Under the nom-de-plume Mrs. Crackenthorpe, she later, after criticism, announced that the authorship was broadened to include a Society of Ladies. And thus, the concept of a periodical headed by a group of collaborative co-editors was actually introduced by women. The Female Tatler was also, after an initial brief acrimonious stint with a male publisher, published by a woman, Mrs. A. Baldwin2. Women working together to write and publish women’s writing for a primarily female audience.

With varying points of view, The Female Tattler wrote about politics and other issues that were not typically thought to be the subject of women’s conversation in public. Intended for both men and women, it advocated for women’s education, with essays and advice on how to navigate so many of the social strictures women were told to follow.

While there is some question of authorship in its entirety of The Female Tatler’s printing, there is little question that Manley was involved and that it was “written by women, for women” as it proclaimed. The fictional Mrs. Crackenthorpe proclaimed as much with as great a comeback as many female writers of politics today:

Whereas several ill-bred critics have reported about town that a woman is not the author of this paper, which I take to be a splenetic and irrational aspiration upon our whole sex, women were always allowed to have a finer thread of understanding than the men, which made them have recourse to learning, that they might equal our natural parts, and by an arbitrary sway have kept us from many advantages to prevent our out-vying [sic] them; but those ladies who have imbibed authors, and dived into arts and sciences have ever discovered a quicker genius, and more sublime notions. These detractors must be a rough-hewn sort of animals that could never gain admittance to the fair sex, and all such I forbid my drawing room.

Has any woman writer not felt similarly, when trolled by men?

In arguably one of its more powerful issues, the co-editors go on to write:

Why should we be treated almost as if we were irrational creatures? We are industriously kept from the knowledge of arts and sciences, and if we talk politics we are laughed at. To understand Latin is petty treason in us, silence is recommended to us a necessary duty, and the greatest encomium a man can give his wife is to tell the world that she is obedient. The men, like wary conquerors, keep us ignorant, because they are afraid of us, and, that they may the easier maintain their dominion over us, they compliment us into idleness, pretending those peasants to be tokens of their affection, which in reality, are the consequences of their tyranny.

In another issue, the author had to refute a ‘gentleman’ who wrote a letter to threaten her, saying he would cut off her nose were she to visit his address, and dared her to do it. She, needless to say, refused.

Eliza Haywood published her first novel, Love in Excess, in 1720, bursting onto the literary scene with wild popularity, and a run of six editions.3 She went on to become one of the most prolific writers of her day, publishing over 70 works in her lifetime, spanning from fiction, plays, translations, poetry, and conduct literature, in addition to periodicals. Haywood was also unabashedly political in her work. When she satirized Tory satirists in her book Memoirs of a Certain Island Adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia in 1725, Alexander Pope publicly derided her work as that “most scandalous book,” among other epithets.

Haywood stopped writing for a decade—some conjecture it was the public derision of Pope that had been the cause. When she began to write again in the 1740s, Haywood created, wrote, and published The Female Spectator, a periodical in the style of the male-written The Spectator, which, like The Tatler before, assumed a ‘universal’ white male audience. Yet differing from The Female Tatler, The Female Spectator was almost solely intended for a women’s audience, with men a peripheral, if absent presence. Much of it was devoted to aphoristic wit and morality, with a pragmatic acceptance of what roles were available to women, born into a world they could not control. It was ignored, patronized, and misread by men as a result—with very few critical studies ever referencing her work.

When Haywood was attacked by a male correspondent as a “Vain Pretender to Things above thy Reach!,” she refutes his idea that the best way to comment on the political, public sphere would be to repeat the factual reports of “News Mongers” of the day. She clapped back:

Several of the Topics he reproaches me for not having touch’d upon, come not within the Province of a Female Spectator;—such as Armies marching,—Battles fought,—Towns destroyed,—Rivers cross’d, and the like;—I should think it ill became me to take up my own or Reader’s Time, with such Accounts as are every Day to be found in the public Papers.

After The Female Spectator ended, Haywood returned to satire with another periodical, The Parrot. Writing as a “bird of many parts,” she uses her fictional position as a creature outside of society as a means to comment on its problems. And they are strikingly modern. Media spectacle and culture are menaces the world has long been contending with:

POOR Poll is very melancholy,—all the Conversation I have heard for I know not how long, has been wholly on Indictments,—Trials,—Sentences of Death, and Executions:—Disagreeable Entertainment to a Bird of any Wit or Spirit…is there no Pity due to the living Relatives of those unhappy Persons, who, though innocent, must suffer in their Kindreds Fate?”

She laments that her position is so “alien…in these Kingdoms.” As a green parrot (a color that may have signaled Jacobite support), Rachel Carnell writes that Haywood:

allows the color and species of her feathered persona to stand for more than just her sex and indeed to stand for a broad spectrum of differences from the dominant bourgeois, white, Anglican, male public sphere, whose interests Kathleen Wilson has described as defined by ‘gender, race, productivity, and profits.’ The difficulties posed by ‘being green’ represent the broader problem of exclusion from a public discourse whose images of friendship and sameness tantalizingly suggest the potential for universal inclusion.4

I can’t think of a better summation of the way media coverage is still focused: gender, race, productivity, and profit.

Unlike Haywood’s ideas in The Parrot, the absolutism in free speech arguments we hear today fails to acknowledge the obvious and grating fact that we do not have universal inclusion. Words cause harm in ways that threaten lives. Without protecting the public good of dignity and inclusion, free speech is always at risk of being weaponized. Having to absorb racist memes and misogynist harassment sends a clear message that certain groups’ security is under threat, and in no way guaranteed.

The idea of free speech as framed in the Constitution was heavily influenced by two other London journalists, Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard. Their anonymous column Cato’s Letters was best-selling and widely published and re-published on both sides of the Atlantic for decades. As they sought to define the parameters of free speech, they also defined what the term ‘public’ entailed. As as a result, they also defined gender roles into more distinct ‘public’ and ‘private’ spheres—an idea that refuted the contributions of so many women’s voices engaged in public and political debate, like Manley and Haywood. Gordon and Trenchard—the originators of how we think of free speech today—believed and fostered a view that ‘public’ speech was fundamentally for white propertied men. It’s no little irony both men were also involved in the slave trade.

In the early Americas, the ideology of free speech mainly buttressed white supremacy. For eighteenth-century white male colonists, freedom of speech was both a potent political ideal and a constant practical marker of their superiority over others. Their law and politics were transacted through oral rituals—like the taking of oaths, the giving of evidence, the making of speeches, or the formal debate of policy—from which lesser human beings were automatically excluded. That meant women, Jews, Catholics, and Quakers, as in Britain—as well as all people of color. The words of mulattoes, Indians, and free Blacks were always inferior to those of whites, while the mass silencing of Black people was central to slavery itself.5

And this is the crux of the issue with the claims to free speech by mad twitter kings and other media platform owners: free speech ideals were fundamentally based on silencing the oppressed. And still do.

It’s reflected in the discussions and arguments around gender and race as mass media began in earnest with newspaper/periodical publishing in the early eighteenth century. A time when men publicly derided women as having no head for politics or learning, and who denied the humanity and voices of any non-white man—crucial to upholding white supremacy and slavery. It’s why the brilliant Phyllis Wheatley had to circulate her work to prominent white men, asking them to assert publicly that she indeed wrote her work and it has merit—because no one would believe it to be the work of an enslaved, black woman otherwise. It’s in the sneering derision when Jefferson wrote of her work, that it is “below the dignity of criticism.” Free speech’s public sphere was only for the thoughts and works of so-called enlightened white men.

And this is why the weaponization and sanctimonious claims of free speech becomes a smoke screen for hate speech and a way to uphold white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. It’s baked into the entirety of the idea.

I’d argue that we need to consider a wider public good as a thing as worthy of protection as is free (hate) speech. More so. Because claims of free speech have always been and continue to be most useful to those who are in power as a means to refute, silence, and condemn the needs of others. As Kate Manne writes:

Oppressed people are often met with the political analogue of stonewalling. In order to be heard, they need to shout; and when they shout, they are told to lower their voices. They may be able to speak, but have little hope of being listened to.

Or as Fara Dabhoiwala summarizes:

The free speech of some is established through the silencing of others.

Apologies to non-substack writer/readers—Notes is a new product that acts a little like a twitter feed, but for the most part it has been kind of a lovely community hangout of writers. I’ve already learned of new writers that I am excited to read. But there are always those who emerge to throw some poison around, unfortunately…

There is a long history of women publishers and booksellers. Unsurprisingly, much of history has ignored this. See e.g., McDowell, Paula. 1998. The Women of Grub Street: Press, Politics, and Gender in the London Literary Marketplace 1678-1730. 1st Edition. Clarendon Press

Of course in a search of antiquarian book sites, I haven’t been able to find any extant copy of Haywood’s works—what some scholars have called the most prolific writer of the eighteenth century.

Carnell, Rachel. “It’s Not Easy Being Green: Gender and Friendship in Eliza Haywood’s Political Periodicals.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 32, no. 2 (1998-9). p. 206

Dabhoiwala, F. (2023). Liberty, Slavery, and Biography: The Hidden Shapes of Free Speech. Journal of British Studies, 62(1), 104-131. doi:10.1017/jbr.2022.230

Notes - just no interest in going there.

Lots to think about - is free speech under attack from free speech?

Antonia has firsthand knowledge of this infamous Montana event:

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-superhuman-mind/201903/should-hate-speech-be-free-speech

As you always pique my curiosity, I found this for you to enjoy. Remarkable women, these two.

https://bwht.org/ladies-walk-tour/#:~:text=Although%20we%20have%20no%20record%20of%20them%20ever,from%20one%20another%20during%20the%20Revolutionary%20War%20period.

What an interesting history! I had no idea of much of this. The quotes from The Female Taller are right on point, aren't they?

I've seen and experienced first-hand the physical real-life harms that absolute free speech in the way you're describing (as a tool to silence the oppressed or marginalized) causes. I never want anyone to have to go through that. The history you're unspooling here is important, so we understand how truly little of this is new, and where it comes from.