As I write, it is midwinter—that pause in the season when the sun rests in its path across our skies. And with the pause also comes a return, a turning towards what was left behind, at the same time we look towards a lightening horizon. The name January, after all, is named for Janus, the god of endings and beginnings, thresholds and doors. A both/and time of year, waiting to see what might arrive to meet us when still, before the need to move again into a new year.

I've been at a pause myself the last couple of months, looking back and forward. I’ve moved from Anchorage, Alaska, after making a home there for over two decades, returning to Oregon, where I was born and lived most of my earlier life. It’s been a time of so many transitions—leaving a home we loved but knew it was time for change; the offer of a new job; our son headed to college for his first term. It’s been a time of learning to live in uncertainty—or more of being reminded that we always do live in uncertainty, no matter how stable a place we believe we’ve made.

It’s an odd thing to become familiar again with things that also feel...well, familiar. To turn a corner of a road and see the familiar shape of Wyeast (Mt. Hood) greeting us above the horizon, a sight so familiar it feels like seeing my own name—yet I had forgotten about that recognition of place so early in my memory.

I thought of this as I have been reading a book on traditions of memory, reading, and wisdom. It describes memory—particularly when experienced with others—as a communal return to consciousness. Memoria was a reason for a community to assemble, the means through which consciousness arises, becoming a new people. I was struck by the significance placed on the collective recognition of memory. How interesting to think of memory as the doorway through which to become something else, something new, to find some new, collective consciousness.

Becoming re-acquainted with a place so familiar but the details of which have been far out of mind feels like such acts of memory. To reacquaint with old friends, family. To remember details about the way the air feels after rain, the ways to move in the city that is more muscle memory than predicated on maps and names of roads. The birds that are most common, how the land stays green in winter. Maybe a return to what is familiar is a kind of memory, to awaken a new consciousness. To move towards a new way to live and be built on both past and future.

Solstice in Anchorage was always a sigh of relief, the darkest day had finally come and light would begin to return. To feel the zenith of having made it through the winter’s darkest days. In the last few years, I had taken to turning off all the lights and lighting candles around the house in December, to really feel the soaking dark. It was hard won, but in the last few years I had grown to love the quiet, the do-nothing feeling of darkness, the call to hibernation that we are supposed to ignore but that is still strongly pulling at us, like gravity, asking us to slow down.

Being in Oregon at the solstice is a different kind of dark—the grey rainy mossy foggy wet dusk that I had grown up loving. The mildness of it—the air cool enough to feel wintry, but still never feeling like you have to put on armor just to walk outside the door. The first few weeks here I did miss the cold—and still do at times, especially the snow of the last few winters in Anchorage—but at least here there is rain. Rain that begs for drinking tea, reading, quiet. Rain that plays with fog in the trees, and dances on roofs at night. Rain that soaks and sinks into the skin, a place where salamanders can thrive without threat of freeze. I walked out into the yard last night in bare feet, enjoying the cold jolt of the patio stones on my skin at the house we’re renting, and delighted to look up into the night sky and see stars—to be able to linger, to stay out and just gaze at them in air that didn’t threaten to take my breath away. Stargazing in Anchorage was always a very, very cold and brief affair. This offered time to pause and enjoy their light.

I thought of how in earlier times there were no clocks by which to read the time—that time was tracked through seasonal turns, through the waxing and waning moon, the sunlight hours. How the thirty-six fixed stars were considered horoscopi—literally, time-watchers. Stargazing was—is—watching time. Or time watching us.

The move south and all of its needs have been a swirl—all the endless tasks and red tape and name signing and negotiating that comes with a new job, selling a home, looking for a new one, renting with dogs in tow. We’re still waiting for furniture, the sale of our house closing at the new year. Remembering how it is to live in mostly empty rooms, with folding chairs and a table I broke down and bought before I picked up my son from school for Thanksgiving. I am trying to sit with patience (something my nervous nature is not particularly skilled at).

Because of the unpredictability we’ve inserted into our lives, I’ve been trying to stay focused on what is close at hand—a noisy road, but also the welcome of a garden that someone put in many years before we arrived. Of the hummingbirds that buzz and vip by as I walk towards an apple tree—both entirely novel and magical after living in the north for so long. And so, to quiet the whir of it all, I also find myself paying more attention to patterns since the move—that undeniable need to find meaning in this new, familiar place.

We’re warned so often that we look for patterns as a crutch, a false or misguided attempt to create order out of chaos. That we can’t help ourselves from ascribing meaning to things, events, occurrences, appearances and should thus ignore them. That we should avoid falling to anthropomorphism with animals we love (the original meaning of the word study). That I should refuse to believe that a hummingbird I watched with delight one morning as they decided to fly across the garden and nearly into me before noticing their mistake doesn’t have some deeper significance. It may not have been meaningful for the hummingbird, but it doesn’t lessen that I still remember the sound of their wings and bright blur of green-gold feathers so close up weeks after.

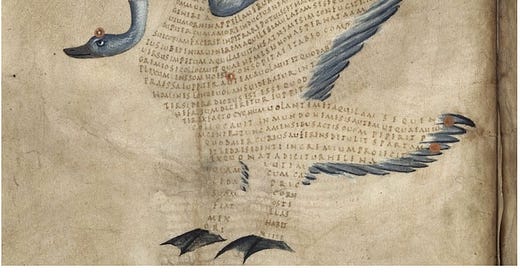

Symbols, after all, were once believed to be a material bridge to understand the invisible.

What if the owls hooing to one another among the trees one night as my son and I arrived at this temporary home made us feel seen and cared for and hopeful? What would we miss if we passed such instances off as nothing-to-see-here, no-meaning-to-be-gained, not-meant-for-you?

What if we seek these patterns out not because we’re trying to create order, but because we really are creating order—order for ourselves, if not for the reality around us? Noticing, finding patterns means that we’re seeking out where we fit into the story around us. That we’re aware of a story around us.

There’s something in all of those teachings that doesn’t sit well with me, and even more so as I try to fit into the rhythms of a new place, season. If we drain the world of meaning, refuse the patterns we might be lucky to witness, patterns that cause us to think and wonder, what on earth are we doing? It becomes yet another instance of being admonished to distrust what we feel and think for some more objective reality that is frankly, not all that fun to be around and protests far too much.

There’s a line in the book I'm reading about a 13th-century text that describes the way order was understood at the time:

‘To order’ means neither to organize and systematize knowledge according to preconceived subjects, nor to manage it. The reader’s order is not imposed on the story, but the story puts the reader into its order….Medieval poets and mystics stress the motive of the hunt, pilgrims are constantly in front of a fork in the road. All are in search of symbols, which they must recognize and find by finding their own place within the ordo.1

It seems to speak to the kind of story that puts us into its order, not the other way around. Stars as time-watchers, not us watching time.

We are taught to be objective, that we are always the observer—rarely considering that the patterns we see, notice, and yes, create, are our way of interacting with the story, with life, with the world around us. If we ignore the patterns, we’re reconciled to living with just noise. What might it mean if we shift the balance and consider how we are a part of what is being observed?

Because as Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote in Aurora Leigh: “…Being observed / when observation is not sympathy / is just being tortured.”

As I write I have turned off the lights and lit a candle near my notebook, waiting to see what the return of the light will slowly bring. What will return with it and what will not, of allowing time to watch us and allow us to find where we can best find ourselves in the story. It feels like this kind of pause, of waiting to see what will arrive to meet us is a kind of giving over, the best sense of surrender—because it asks us to trust that the path will be lit again, however slowly, in whatever way it both does and does not coincide with what came before.

If we observe with sympathy, allow the story to reveal itself to us, we can become a part of a story that is larger and wider. Notice the patterns and allow their reality to lead us to what is perhaps not yet visible.

Perhaps then we can also store wisdom where it was believed to have once resided—in the heart.

Happy Midwinter to all of you—and thank you so much for being here as I paused to find new patterns from which to write.

Illich, Ivan. 1993. In the Vineyard of the Text. University of Chicago Press. p. 31

Oh, that Elizabeth Barrett Browning passage! Thank you! And for all of this.

Thanks for your beautiful writing.