I go back and forth when I get ready to write. I always convince myself I need to read more. I love reading—it’s a journey, it’s knowledge, it’s daydreaming, it’s puzzling, it’s finding connections and explanations. It’s a kind of flow, trance state.

Writing, on the other hand, is not. I love it, need it, but it’s always demanding and hard. Hard to put the connections on the page in a way that I feel it in my mind, that isn’t just a description, but a feeling, a sense of questioning, of not knowing but asking more.

But I always surprise myself when I find a declarative sentence looking back at me on the page. I worry I’m trying too hard to convince myself. And others. I always doubt before hitting publish. And after.

Women are so conditioned to doubt our selves, our bodies—although I’d hazard a guess that self-doubt is inscribed on the bodies of all non-white men and hell, even some white men. Doubt is a part of not wielding power.

For women particularly, though, there’s a profound sense of mistrust that we absorb as our bodies become adults. Our bodies begin to bleed—and since the world is designed for and by men, bleeding bodies are something to mistrust, hide, control. We learn as we become women that our bodies are now viewed as objects—boys we grew up with start to notice our different bodies, as do adult men (creepily). We learn that our bodies are not enough, that we are supposed to adorn our bodies, wear makeup, control what we eat, and shape our bodies to look more like the ideals we are bombarded with on screens. I’ve written about it before1 but for girls, puberty can be an experience of trauma. It’s when we learn that our bodies have to be controlled, made smaller, our faces more colorful, our voices less loud. It’s when we learn we’re supposed to take up less space. And the reminders are incessant. Girls learn that their bodies are objects to be adorned, inscribed with what it means to be feminine—and inferior.

Self-doubt becomes a practice, a way of moving in a world that doesn’t make room for a woman’s authority. If the world doesn’t take a woman’s voice seriously, why should a woman feel that she can speak without doubt? As Regan Penaluna writes, in her fantastic memoir-scholarship-history on women philosophers How to Think Like a Woman:

The takeaway: to think like a woman is to be regularly ashamed of oneself.2

And yet. An aspect of living with doubt is that it makes you ask questions—of yourself, but also of others. And while we’re conditioned to find it effacing and inferior to live with self-doubt, there is also something generous in that doubt—of not assuming others always want to hear one’s voice, to gauge the trust and interest another holds in conversation with us—to be mindful of others, to make room for others as we take up our own space. With self-doubt, we are honed to ask questions of the world and to listen for a response. Self-doubt becomes a gesture of interdependence—it’s a way of moving through the world conscious that you do so alongside others who have the same right to exist.

Penaluna writes:

It’s not surprising that the philosopher who introduced the idea of radical doubt [Teresa of Ávila, a sixteenth century nun and philosopher] was a woman, since women learn to question themselves from a young age. Contemporary philosopher and artist Adrian Piper noticed this too. She says that women are especially adept at philosophical doubt because ‘their lack of judgement, credibility and authority start to come under attack during puberty, as part of the process of gender socialization. They are made to feel uncertain about themselves, their place in society and their right to their own opinions.’3

And I liked the turn that the inscription of self-doubt took in my mind—that old chestnut that perhaps what we are criticized for is actually something redemptive, a sign of what’s lacking in the rest of the world, and the reason it’s coded as inferior. If self-doubt is so widely dismissed, there is some power underlying it.

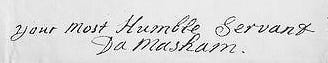

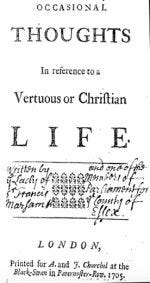

Damaris Cudworth Masham was a fascinating philosopher—someone who was filled with self-doubt and still managed to recognize that it was a key strength in seeing what was wrong with society. Writing in the seventeenth to eighteenth century, her published work was largely forgotten, until it was republished in 2005—and maddeningly, only to soon be out of print once again.

Cudworth Masham was born in 1659, the daughter of a Cambridge philosopher who believed in women’s education. And tantalizingly, she was able to live and be around campus at a time when women were not allowed at university.4 Damaris would attend the dinners and meetings her father would host—a guest of whom may have been another brilliant philosopher woman, Anne Conway (whom I wrote about in an earlier post), who was a distant cousin on Damaris’ mother’s side. Amazing to think of these women moving in overlapping circles, and yet their names are so little known or remembered.

Damaris began a correspondence with John Locke after he saw her at a mutual gathering and asked to write to her. They discussed philosophy, and also flirtation—it may have been more than that at one time on Locke’s side, and then Cudworth’s, and then not perhaps either. But more importantly, Locke celebrated Damaris’ thinking and he was eager to learn from her about Cambridge Platonism, which was a popular school of thought, but not as pervasive in London.

Damaris Cudworth became Lady Damaris Cudworth Masham when she married a widower with nine children and moved to his estate. She soon became pregnant and was scared of dying in childbirth. She continued to write to Locke, reporting that she was mocked and gossiped about for her learning, for managing her house efficiently, that her doctor “worries that she is concerningly peculiar.”5 She had a healthy son and continued on, writing to Locke, frustrated at the lack of space in the world for a woman to learn and think for herself—to have a life of the mind.

When she was 31, Locke came to visit her, and the Masham estate became his favorite escape from London. Damaris convinced her husband that due to Locke’s persistent cough, he shouldn’t return to London and instead should live with them. It apparently took some convincing, but it worked. Locke paid rent for himself at their estate, taking over two large rooms, and became close to Damaris’ son, whom he taught. Damaris and Locke were never certain as to how to describe their relationship. Rumors abounded. But they worked together constantly.

Yet Masham’s philosophy differed from Locke’s, and she was in no way his disciple or student. Her work isn’t based on metaphysics or epistemology, but on the way that social forces impinge on women and keep them from a life of the mind.

What I love about Masham’s work is that she refuted another rather famously too-often-obscured woman philosopher/writer, Mary Astell. While Astell had much to say for educating girls and advocating for the rights of women, Masham took issue with Astell and another philosopher, John Norris, for condoning the works of Nicolas Malebranche, a French philosopher who “proclaimed that mothers inflict irreversible cognitive damage on their babies while in the womb.”6 Essentially, because they are weak, inferior, sinful women.

Masham vehemently refuted this in her first work, and it formed a basis for how she thought of motherhood and parenting as essential to understanding the significance of a relationship with God (because God was always part of philosophy in this era). Unlike Malebranche’s idea that God is the only action in the universe, and all created things are thus inert, Masham believed that nothing that existed—i.e., nothing of God’s creation—was made in vain. As Penaluna writes:

Masham was creating the logical conditions to persuade us that God gave things in creation causal powers. When a person or thing pleases us, we are not wrong in desiring or loving it, which to her were the same things.7

Masham wrote:

We love our Children, or Friends; It is evident also from the Nature of the Object, that we not only wish to them as to our selves, whatever we conceive may tend to continue, or improve their Being; but also, that Desire of them is a necessary Concomitant of our Love.8

Love is what is essential to living a moral life—loving people, loving the world. And mothers play a significant role in that philosophy—by being the first

transmitters of love who set us on the path of inquisitive engagement with the world. Mothers help make philosophy possible.9

Masham’s second work expands on these ideas but with an important addition—the fundamental need to question the authority of teachers. She made this point, particularly with an eye toward the education of girls:

Children, girls especially, were ‘brought to say, that they do Believe whatever their Teachers tell them they must Believe; whilst in Truth they remain in an ignorant unbelief.10

‘Teachers’ is of course a broad category—meaning all men who would ‘teach’ women. Though men might believe themselves to be superior, Masham wrote:

The Knowledge hitherto spoken of has a nobler Aim than the pleasing of Men.11

Part of her argument is based on the offensiveness of how rational women were treated—that they were made to feel “contemptible”—and she directed that ire squarely at men who

are ever desirous to find out such Rules for other People, as will not reach themselves, and as they can extend and contract as they please.12

Reading those lines I thought of the times I was made to feel contemptible at work by those with power over me—most often white men, but also white women. I was harassed, at times with insinuatingly blatant remarks. I was told by a male colleague I’d never be seen again once I gave birth to my son. White women told me I didn’t really need the job—so why am I applying for the leadership position, when my husband already works? I was told more times than I care to remember that I was being emotional, I should smile more, I’m too passive, not a doer. That I was never working enough (despite often working 12-hour days, at home and around the clock, desperate to be more than just a satellite in my son’s life as a ‘working’ mother). Self-doubt goes hand in hand with being questioned and made to feel contemptible for anything related to my own subjectivity. Work became a charade, a cosplay of trying to pretend I could work and live as a white man. (Reader, I failed).

Penaluna writes:

Masham wrote about what prevents a woman from committing to an intellectual life: the unwritten, automatic, continual message that she isn’t fit for it. Censure, ridicule, and isolation are strong enough forces to make her doubt herself. They beat her back like waves against a dinghy…All these questions suggest that the epistemic state of many a thinking woman is one of self-doubt.13

Based on my own experience, that rings true like a loud bell. Too often women and non-cis-white men are conditioned to take up less space, only to be beaten back when they try to take up any space, no matter how small they keep themselves, in a society that was never built with them in mind.

So as I was reading about Masham and Astell, I thought more about self-doubt as an avenue that invites questions, to think critically about what we see and experience. To not accept at face value and instead think deeply about the experiences we have, the conditions we are faced with. To not get smaller when we are pushed back, but notice it as an indication that we’re doing something right in being there, in asking the question, no matter how wearying. Questioning and self-doubt are reminders to keep going.

Self-doubt means that we look to others as well as ourselves, as long as we don’t let it consume us. Questioning leads to engagement with ideas, with others. It works in interdependence, weaving people’s lives and ideas together. When we don’t question, we not only isolate, we alienate. Convince ourselves that there is no reason to consider another’s opinion, or authority. Doubt is what leads to asking better questions.

Masham believed that questioning authority was vital in trying to live a moral life. And she also believed in the power of empathy and love as the keys to a life well lived. Ideas which are about engagement with the world as beings and creatures of agency and will, in community—all part of creation. She believed that life is about the beauty of desire, of pleasure, of loving others, loving places, and other creatures. To question as love, to love as a question. As Penaluna writes, Masham’s believed that

…the only path to enlightenment is transcendence through interdependence.14

Masham’s ideas are in direct opposition to the ideas of male philosophers like Descartes and Malebranche, or Kant and Thomas Aquinas. In their philosophy, love—between humans, love of other creatures, a love of place—was believed to be a detriment to living a true life. Love can hurt you, make you sick, cause you harm, make you attached, vulnerable, dependent. Weak. Their ideas held that it is better to live an unaffected life, only concerned with the life of a mind turned towards God. Masham thought not:

The love of others is a treacherous but necessary path and the only one available to us, because we are not gods.15 (134)

Reading about Masham’s ideas, it all makes me want to love more fiercely, question more defiantly, take pride in questioning my own actions and feelings, as well as of others, and to rage with anger when necessary. All of it is necessary and moves in a way that this society would still beat out of us.

Penaluna summarizes Masham’s thought this way:

Do not retreat. A woman’s path to self-knowledge requires her to risk losing herself to find herself.16

I went for a walk after writing the above. It’s noticeably warm outside—45f feels like 70f after days of successive melt, and kids are out wearing shorts. I’m out with no coat and it feels revelatory, freeing. The birds have been back but the ones in my tree have been noticeably less—I worry about if an owl is in the neighborhood, or if there has been a population decline. Worrying is an act of love, I think to myself. I can hear the newly returned seagulls, geese, and the occasional sandhill crane, whose voice is like the rattling of an alto water-flute—I always wonder what kinds of rattle calls pterodactyls may have had when I hear cranes call.

There is still so much snow, but it is receding each day above freezing and my bulldog seems to enjoy that there are patches of grass revealing themselves, and I love his enthusiasm. We turned the corner and in the breaks of open water in the still-frozen pond, I was met by the eye of a mallard drake, his head shining in the sun. A few moments later a hen joined him, emerging from underneath the bridge moments later. His dark green head a consoling reminder—green will be everywhere again before too long.

A couple of small butterflies were out despite the snow and lack of bloom, and solitary bees are flying along the south-facing banks that they always nest in. The sound and sight of these winged creatures returning north always feel like a bit of a miracle—it’s always so softly surprising to see the landscape start to turn—that the landscape can change so dramatically from what it is in summer to what it is in winter. How the animals know before we can see any sign of it. I woke thinking the other day, as I heard the gulls call in the far-too-early hours, that spring arrives here not with blooms, but with wings.

Solitary bees aren’t necessarily solitary, but they don’t live in hives—they live most of the year underground, dormant, feeding as larvae on the stores that their mother collected for them before she died last spring. They only live for a few weeks as bees, collecting pollen from pussywillows as they bloom from fur to flower. The small singular work of collecting pollen for the next year’s progeny, digging into the earth to line a small cell.

It feels impossible that these lives are around us in such stages of transformation, that we only see one small window of what their lives are like. But when I see them I greet them as long-lost friends, returning.

And I thought of Masham. How different a life would be if we believed in our own bodies and what they know from the beginning of our lives—that it was never beaten out of us what we need and feel is actual and real. To refuse legacies of thought that condition us all to be non-bodied and hold a false, god-like indifference as an ideal.

Masham’s philosophy would have us love the places we live and not be embarrassed or thought uncommitted to a career by being too attached to a sense of home. That prioritizing mothering, empathy, and care would be the height of success. To know in our bones that the lands we live on and with, and the beings around us, should be loved with bold subjectivity. To trust and doubt, question and know—to try and hold all in relationship to one another. To be a mess and still believe in transcendence.

How different it would be to live by a philosophy of loving our way through life.

with apologies for sounding redundant…although that’s another thing I’m learning to question, the need to always be new…

Penaluna, Regan. 2023. How to Think Like a Woman: Four Women Philosophers who Taught Me to Love a Life of the Mind. Grove Press Atlantic. p. 125

Ibid. p. 121.

Women were not allowed to enroll at Cambridge until 1869. The first woman to have a degree awarded, incredibly, was in 1948.

Penaluna, p. 105.

Ibid. p. 108.

Ibid. p. 111.

Ibid.

Ibid. p. 113.

Ibid. p. 114.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid. p. 120.

Ibid. p. 134.

Ibid.

Ibid.

What a powerful reframing of self-doubt. Love this, thank you for sharing!

Thank you for taking the time and effort to do this beautifully researched and written piece,!