I recently finished a book on Louisa May Alcott and her mother, Abigail May1, who became the first woman to be a social worker in Boston. Abigail was a feminist and fought for a better world her whole life. She had believed that by eschewing her father’s plans to betroth her to a respectable cousin she didn’t love, she was making a bold decision in choosing her own partner, in marrying for what she thought was love, when she wed the poor, transcendentalist head-in-clouds Bronson Alcott, friend of Emerson, Thoreau, the Peabodies, and Hawthorne. Instead, Abigail found herself becoming even more entrenched in the gender roles and confines of patriarchy that she had hoped to escape.

Abigail quickly learned that she would have to find ways to support her growing family. Bronson Alcott would repeatedly leave her for months while he pontificated on a life of the mind in public speeches that garnered little to no earnings. Abigail was repeatedly forced to ask friends and relatives for money to survive and feed her family, much to her shame, anger, and frustration.

The Alcotts were rarely able to afford a home and moved over thirty times in 15 years, renting and purchasing at times with the help of Abigail’s inheritance, her brother, and Emerson. One particularly bad move was to a farm christened Fruitlands, where Bronson’s dream of consociate living, as he coined it, was to be fulfilled. As Richard Francis writes,

As living experiments go, Fruitlands probably ranks among the more ill-conceived utopian communities ever attempted…It lasted through only seven months of 1843, from June to January, and included just fourteen people; their diet consisted only of foods which would not give up their life force (i.e. are replenished on trees and vines), though they didn’t in fact have many fruit trees on their eleven acres. They lived off the land, though they had little farming experience and forbade animal labor or fertilizer. They aspired to celibacy, though they had five children among them. They possessed a vast library but could not read after dark, because they could not use oil lamps or candles (both derived from animal products). The idea was to return as nearly to the Garden of Eden as possible, but between the infighting, the brutal weather, and poor health, it amounted to a camping expedition in hell.

During the first and only harvest at Fruitlands, the men left to go visit a Shaker community to find recruits. When storms threatened to destroy the crops they did have, including grain that was standing in the field, it was Abigail who, with her daughters, gathered in the meager harvest.

Bronson Alcott was not easy to live with even when he was living with the family under the same roof, which was chronically infrequent. He at times openly questioned whether marriage was a lofty enough enterprise, threatening separation with Abigail and the children. He routinely left Abigail and his children for months—not always to be on the road to give public lectures, but simply to write and think, such as when Abigail was pregnant and trying to support and care for her two toddler girls at the same time. He was absent for much of Louisa’s infancy, despite his belief in the much-needed influence of a father on a child’s development. He also left the family when their daughter, Lizzie was dying. This, from a man whose major professional focus was on the development of new schools based on the Socratic method and child development—who employed Elizabeth Peabody and Margaret Fuller at separate times. Elizabeth left the failing school in disgust; Margaret Fuller did as well after Bronson could not pay her after months of work.

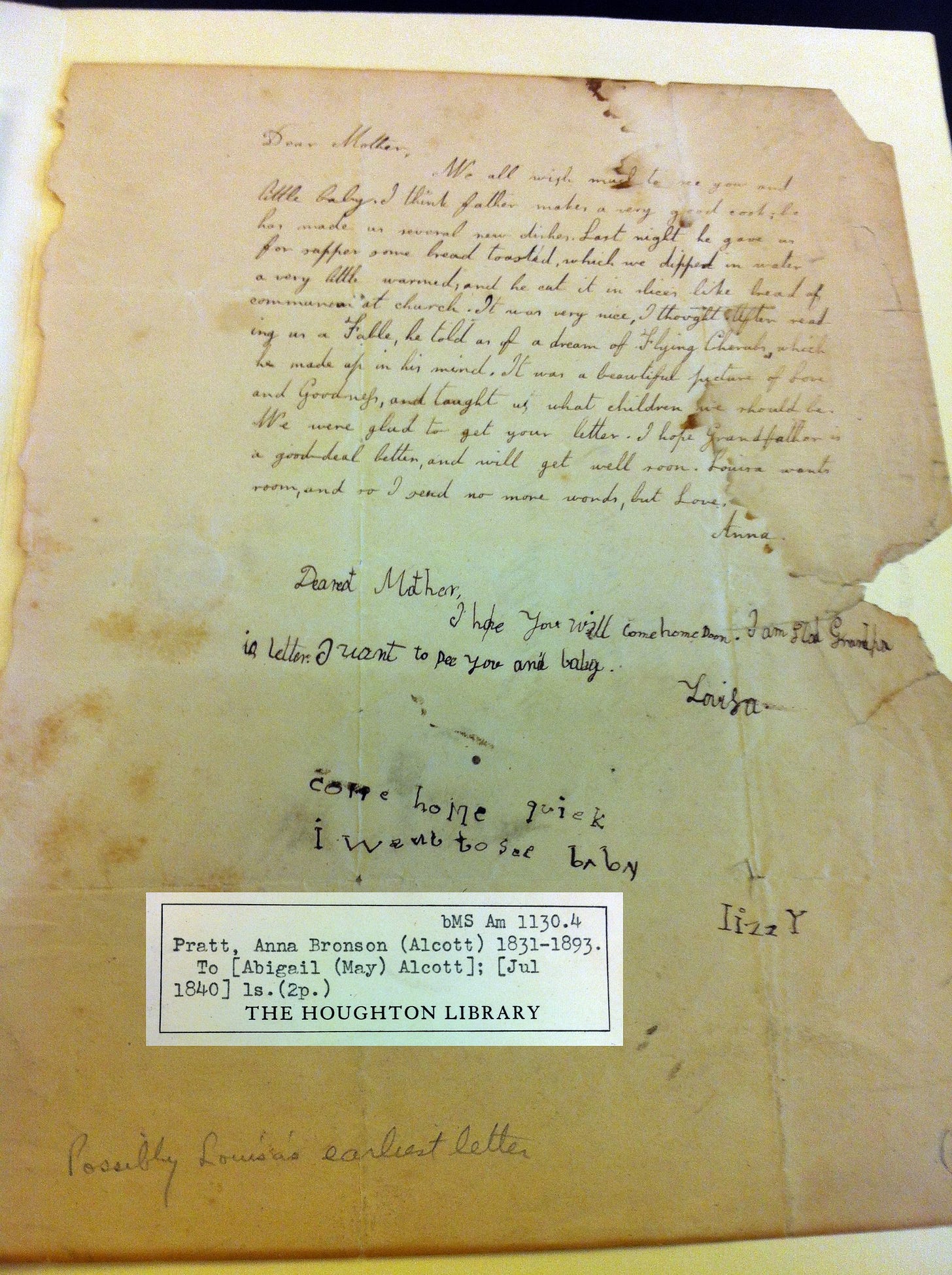

It was a portrait of marriage that Abigail’s surviving daughters—Anna, Louisa, and May—did not want to repeat. Anna still believed hopefully in an egalitarian marriage, but was met with the death of her husband at 40 and two young sons in tow, leading her to move back home with Abigail in similar threats of poverty. May married at 38, after becoming a recognized artist in Paris, but died within a year of giving birth to her only daughter. Louisa never married and—like her mother—became parent to her niece, after mourning the death of two sisters.

Margaret Fuller wrote that “A man’s ambition with a woman’s heart is an evil lot,” in her book Woman of the Nineteenth Century, published when Louisa was twelve. Fuller goes on to write: “One should be either private or public. . . Womanhood is at present too straitly-bounded to give me scope.”

Like Fuller and so many women across generations, Louisa and her sisters fantasized that marriage could be a union of equals—but that would be impossible while women were considered inferior to men in law and custom. The many women who wrote, advocated for, and demanded suffrage and women’s rights throughout the nineteenth century led to a broader awareness of these inequalities—leading to one reason why the mid-to late nineteenth century generation was “the least married group of women in United States history, with a record 13 percent remaining single.”2

Louisa would later write that she had “seen so much of…’the tragedy of modern married life,’ [that she was] “afraid to try it…Liberty is a better husband than love to many of us.” When her older sister Anna decided to marry, Louisa wrote that their future “nest” would be

very sweet and pretty, but I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe….The loss of liberty, happiness, and self-respect is poorly repaid by the barren honor of being called ‘Mrs. instead of ‘Miss’.

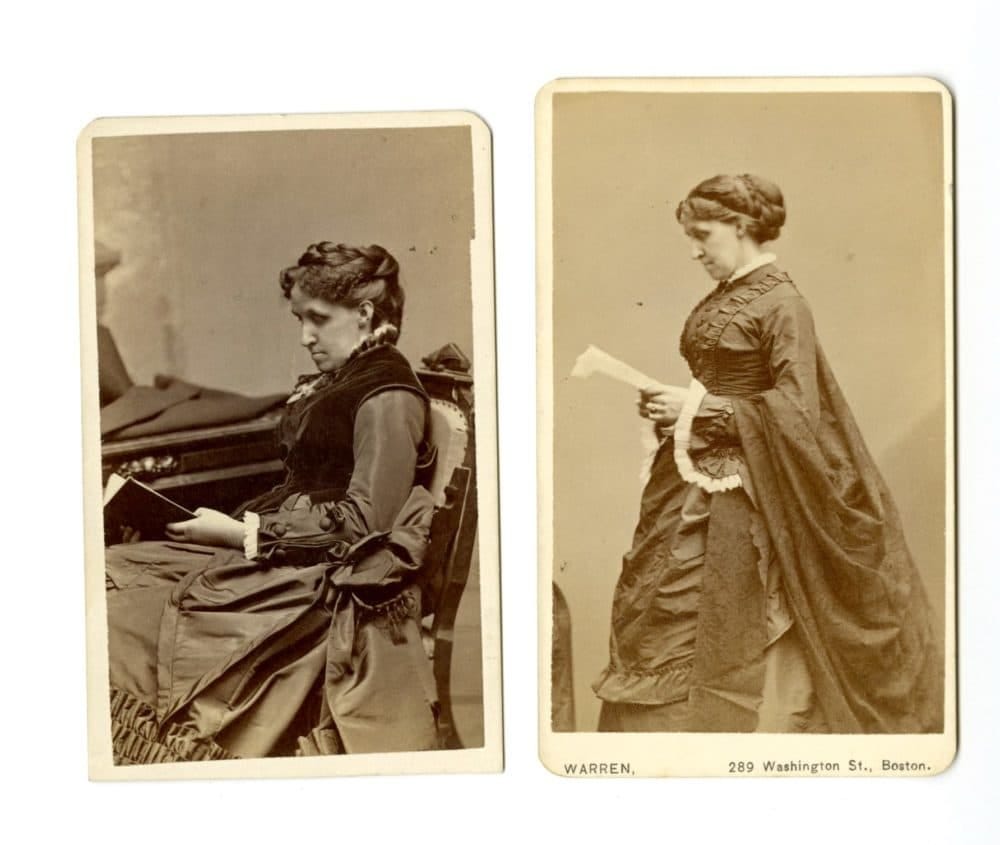

Louisa worked most of her life, from age 15 to age 55 to help support her family—for the first ten as a teacher, governess, seamstress, and servant. When she was in her thirties, frustrated because she could not fight in the Civil War, she left Concord to work as a nurse in a Washington D.C. hospital for soldiers. The work changed her life in more ways than one. She was overwhelmed by all that she witnessed. She contracted typhoid while there—the doctors wanted to send her home but she refused—she instead asked to be treated in the hospital alongside the soldiers. They shaved her head, as was common practice, and administered mercury. She later returned home, unable to continue working as a nurse due to the impacts on her health, which never fully recovered. Her account of that time—published as Hospital Sketches—shot to popularity, the public entranced by an account of the war and its aftermath that so many were only just beginning to realize. In Hospital Sketches she wrote:

I’m a woman’s rights woman, and if any man had offered [me] help in the morning, I should have condescendingly refused it, sure that I could do everything as well, if not better, myself.

With the popularity of Hospital Sketches, her writing—so far sustained in small publications for children and short gothic stories published under a pseudonym—began to show signs of being able to support her family in earnest.

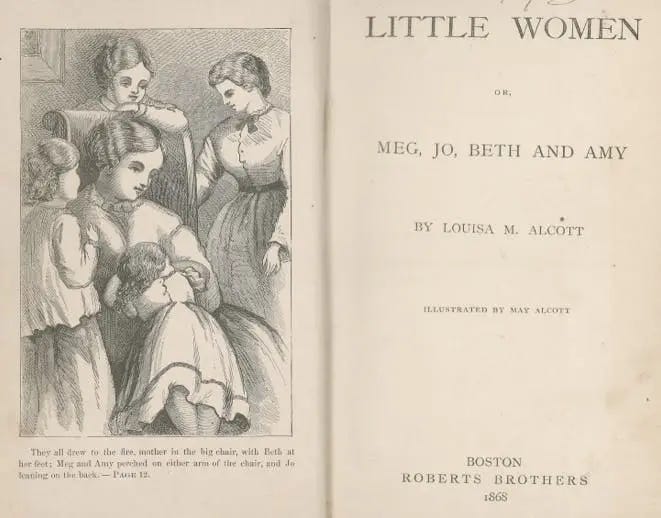

I recently read Little Women again. And true—it can seem saccharine and moralistic, with talk of Pilgrim’s Progress and ideals of moral good. Yet it is utterly enthralling. Alcott brings the reading into those rooms with the four sisters, with Marmee, and Laurie—the parentless neighbor boy who is adopted by the family as one of their own—and it feels so real, so enveloping. And what strikes me even more is how it centers the domestic as being a story—as worthy of story. It is a woman’s book in every sense—despite that it had to be packaged for the approval of male publishers who believed a woman’s story can only be confined to children with moralistic tones, and rarely something that reflected the reality of life for women.

Little Women is about daughters, mothers, sisters, and what the world asks of them—during Civil War, during marriage proposals that are both desired and unwanted, of living a life where dreams of becoming an actor, writer, or artist coincide with the desire to live with close family, and of the precarity of such dreams when dependent on others for support, including those who are absent altogether. It’s a type of mirror image of the hero’s journey, instead focused on Penelope at her loom—along with her sisters and all the other life happening around her—as the center of the story. Weaving and unweaving—times of generosity and lack, largesse and poverty, sacrifice and gifts, of nursing loved ones back to health only to still face their loss as they later die. It is a book about quiet tragedies, joys, and the drama inherent in ideas of everyday. I was surprised at how much I loved reading it.

Little Women made Alcott the highest-paid published author in America, male or female. Not long after its initial publication, there would be forty thousand copies in print, more than any book by any male author of the day.

As I finished the book, I kept thinking about the gender roles that Abigail and and Louisa fought against, and how they both thought they were finding ways to break through them. And yet ironically, each choice still kept the rails of patriarchy in check. Abigail was forced, after choosing a husband she thought for love, to live an emotionally lonely life of poverty and struggle. Louisa’s most famous book is not the gothic ‘blood and thunder’ stories she loved to write, but one focused on the lives of sisters and mothers, centered still largely within the home—a fiction that despite its assumed realism, was one her family rarely experienced, and one that she often wanted to escape from in order to be free to write. Because of her success with Little Women, Alcott was finally able to see her mother, sisters, and her non-working father—as well as cousins, nephews, and nieces—live in comfort without worry of poverty. She was able to give her mother, in the last decade of her life, a life that finally included rest and space to heal from the depression and fatigue she often suffered.

But ironically, the poverty and need of her family—and her success—led to her writing further books that were not based on her muse, but on what a hungry public demanded, going on to write more books based on the characters of Little Women. Her success meant that her muse was tamped down into the domestic scene she thought she wanted to break free from. But maybe this is what is so brilliant—in that she depicted a portrait of a domestic, ‘feminine’ scene that centered women’s hopes, dreams, and the every-day tragedies of trying to resist prescribed roles. It’s a domestic scene of women’s agency, of women who are not defined by the domestic, but by the joys and struggles of being connected to one another as they work and dream. And yet it still is a book that centers women’s lives around home.

And so it becomes a story about the paradox of what home means—home as a driving force of story—the comfort, support, and need of it, the difficulty of finding it, sustaining it—at the same time of wanting to be free of it enough to pursue one’s own interests and talents, to be part and of the world. It’s a story of holding that contradiction, demanding both and all, rather than the opposition of one over an other. It is the longing for a home that is truly a home, with a family that supports one another so that each person can be free.

Alcott’s autobiographical character Jo March was a triumph for so many girls who grew up climbing trees and running outdoors, cutting off their hair and eschewing the vanity girls are conditioned to value, writing with ink-stained hands, imagination running wild. As Jen Stanley notes, the impact of Jo March on women who wanted to write was profound:

Patti Smith, Elena Ferrante, Margaret Atwood and Nora Ephron are just a few who’ve credited Little Women as their inspiration to write.

Little Women celebrates a family of women who triumphed largely without men, who took in a boy who longed for a lost mother, and showed him and others how a life of the hearth—of a hearth to leave and return to, back and forth—is anything but limited. Little Women is a feminist novel that defies stereotypes, no matter how much the public wants to force it into a stereotype of sweet girlhood.

When Little Women was published, it was not marketed just to young girls and women; it was a monumental hit, with everyone—read by young and old, men and women, becoming one of the most popular novels of its time. The shape the books took—their covers and style—became more and more feminized and gendered as the books were reprinted over time.

Stanley also writes, at the time that Greta Gerwig’s other fabulous, feminist movie, Little Women, was released, that:

[Greta] Gerwig said she’s angry that despite [Little Women’s] continued relevance and importance, it hasn’t been given its proper place in the literary canon. It’s not typically taught in schools, and when it is recommended, it seems to be to girls, not boys. Anecdotally, it’s rare that I come across a man my age who has read the book or even seen a film adaptation (I’m side-eyeing my own partner so hard right now)…

Adriana Cavarero wrote, in her book In Spite of Plato:

But I know that con-text (a site where a text interacts with other texts) cannot be created by a single woman on her own.3

As I was reading about Alcott I was struck again at the network of so many women writers, scientists, doctors, abolitionists, suffragists, at the time women like Alcott and her mother were alive. Over sixty women I noted were writing and working in the New England area between Boston, Philadelphia, and New York.4 Nearly all were writing and advocating for progressive causes. I’m sure there are so many more.

One of Abigail May’s favorite writers to read to Louisa and her sisters as they were growing up was Fredrika Bremer—a Finnish-born Swedish writer and feminist. Her book, Sketches of Everyday Life, was popular across Britain and the US in the early to mid-nineteenth century, often cited as a Swedish Jane Austen for her realist style. Bremer helped to change Swedish law by successfully petitioning the King to be emancipated from her brother’s wardship in her late 30s, and later her novel Hertha created a widespread social movement in Sweden to grant all unmarried women legal majority. Bremer’s work inspired another woman, Sophie Adlersparre to create Sweden’s first women’s magazine, and later, the magazine Hertha itself. Bremer’s work to change Swedish law for women’s rights would establish the first female tertiary school in Sweden, and in 1884, she became the namesake of the first women’s rights organization in Sweden.

Another writer Abigail read to her girls was Maria Edgeworth—who, in 1795, published An Essay on the Noble Science of Self-Justification, written explicitly for a female audience to convince women of their own “self-justification,” and advocating that women should always challenge the force and power of men, especially their husbands. Her novel Belinda included an interracial marriage between a Black servant and an English farm girl—a relationship that was condemned by Edgeworth’s influential father and was removed from later editions. While much of Edgeworth’s work is moralistic and didactic, it was steeped in progressive issues and made her the most successful English writer of the time, rivaled only by Sir Walter Scott. It’s unsurprising that Abigail loved Bremer and Edgeworth’s work, and that Louisa and her sisters grew up reading the works of strong, literary women who imagined a better world. Of course, we barely know these women’s names today.

Abigail raised her daughters to believe in gender equality, to fight unjust systems such as slavery and poverty and patriarchy (Bronson would only come around to abolition much later). Abigail was a woman who knew poverty keenly and wanted a better world for her daughters, for all women. She petitioned Congress twice for women’s suffrage, claiming unfair taxation practices in extorting women without representation. Her efforts failed, but she didn’t give up, and neither did her daughters in advocating for abolition and women’s suffrage. She became one of the country’s first paid social workers, in one of its earliest welfare programs, and later opened up an office in her home to support trade unions and city charities. She once wrote to her brother Samuel Joseph May—who was an abolitionist and staunch feminist who similarly helped to initiate women’s rights—that

My life is one of daily protest against the oppression and abuses of society…I find selfishness, meanness, among people who fill high places in church and state.5

When she could no longer keep up the pace of the work, she decided to open her house as an employment agency and clearing house for domestic servants and those in need of work, titled “The Ladies’ Help Exchange.” Louisa called her mother’s office “a shelter for lost girls, abused wives, friendless children, and weak or wicked men.”6

While Bronson kept his study high above the house, he called the work that went on in Abigail’s office, where scores of people came through each day, “a confusing business below.” Louisa would later write of this time in Boston:

All the philosophy in our house is not in the study. A good deal is in the kitchen, where a fine old lady thinks high thoughts and does kind deeds while she cooks and scrubs…. Father idle, mother at work in the office, Nan [Anna] & I governessing. Lizzie in the kitchen. Abba [May] doing nothing but grow. Hard times for all.

Over their four years spent in Boston, Bronson Alcott had earned almost nothing.

Abigail’s determination for women’s equal rights remained strong throughout her life. When she was in ill health, but supported by Louisa’s literary success, Louisa relayed a letter from the feminist Lucy Stone, editor of the suffrage periodical Woman’s Journal—which Louisa wrote is “the only paper I take.” Stone asked for Louisa’s support for women’s suffrage publicly and read the letter aloud to her mother, asking what she thought about her request— Louisa relays in her journals that Abigail replied:

Tell her I am seventy-three, and I mean to go to the polls before I die, even if my three daughters have to carry me!7

Abigail didn’t live to see that reality. But Louisa May Alcott later became the first woman registered to vote in Concord, when women were given school, tax, and bond suffrage in Massachusetts, in 1879.

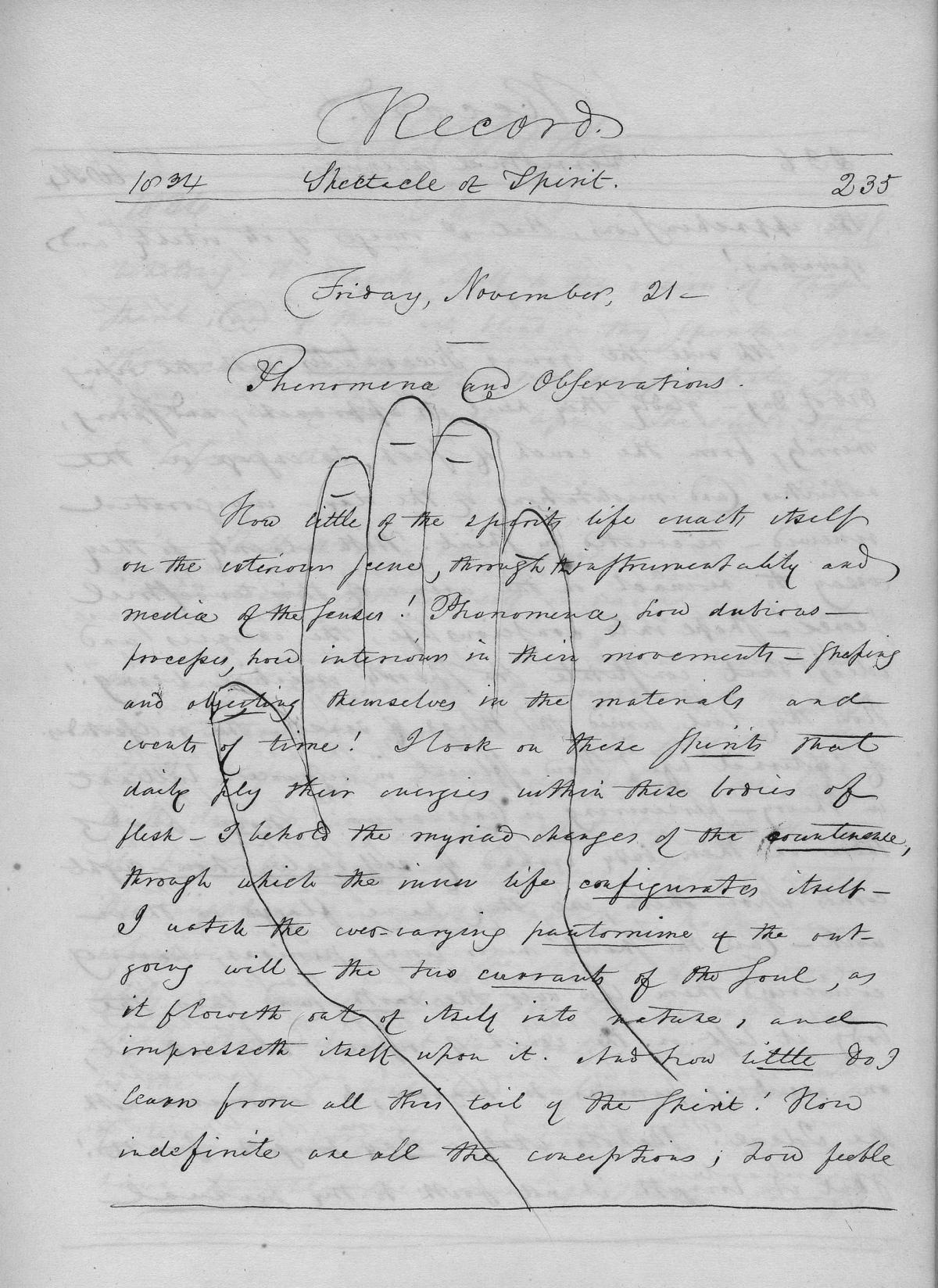

With Louisa’s success, her father found his name gaining new popularity as the father of Little Women. Where Louisa dreaded publicity and attention, Bronson thrived on it, going on book tours in his 70s, espousing the principles that led him to raise his artistic daughters. Louisa’s success burnished his image. Bronson Alcott wrote in his diary of 1864:

Everywhere I am coming into importance…through that rising young lady… [as] ‘The Father of Miss Alcott’.

He went on to write that he was honored as never before. He also noted that no one gave “the mother . . . her full share” of credit.

When Louisa May Alcott died at age 55 in 1888, she was the most popular writer in the country, earning more from her writing than any male author of her time. And yet the myth-making of Louisa May Alcott as a ‘little woman’—a schoolteacher, nurse, writer, devoted to caring for her ailing elderly parents—began immediately. The life or influence of her mother was never cited. Instead, the story of her life became of a young woman whose intellect was uniquely cultivated by the transcendental teachings of her father and friends Emerson and Thoreau. In her obituary, the New York Times wrote:

She was educated as a school teacher under the tutelage of her father and Henry D. Thoreau….Mr. Alcott was stricken with paralysis in 1882, and since that time and up to that of her own fatal illness, she was his constant and loving nurse.8

One of my favorite lines from Little Women is when, after Jo is enraged at her sister’s treachery of burning her manuscript in a fit of anger, Marmee tells her:

I am angry nearly every day of my life, Jo; but I have learned not to show it; and I still hope to learn not to feel it.

I’ve written about women’s anger before—about how often we are told that our rage at injustice, at hurt, at insult is something to temper, to quiet, to make more civil. To read a young woman’s story that reflected the rage that a mother must have felt in her life, of Jo’s anger at her work being destroyed, having to refuse a proposal from her best friend, having to refuse notions of romance over and over in choosing a life of writing and something more—it’s kind of stunning how rarely we get glimpses of this type of anger in a book, written in a time when women were being sanitized into angels in the house. It’s exhilarating to find echoes of that same anger at injustice—ones which have never really gone away, only changed form—in characters from centuries ago. But I want a world where Abigail and other women’s anger can be felt, seen, and heard.

Abigail May Alcott deserves more light for all that she did to support her family and others, despite crippling poverty. As does Louisa May Alcott. To be recognized as feminist mothers born in 1800, with feminist daughters born in 1832, who were raised and inspired by other feminist mothers and writers, no matter how history or the canon insists on their constructed absence.

And Louisa May Alcott deserves more than being thought of as the quiet nurse and writer who wrote children’s books. She was a radical feminist—like so many women—who sought out life and refused to be sidelined. To not let it be forgotten that her first success was Hospital Sketches, which brought to light the reality and horrors of the Civil War, at a time when the brutal violence of that war was not yet understood. She exposed the reality of life in her works—for women, soldiers, including formerly enslaved men who fought for the North—buoyed by networks of women who fought for abolition, suffrage, and justice.

While Louisa May Alcott thought she had had to give up her tales of ‘blood and thunder,’ I’d argue there is nothing more bloody or thunderous—and marvelous—than writing that centers a woman’s life, the care of wounded soldiers, the death of beloved sisters so young, the care of children orphaned by sisters who died too soon in giving birth, the frustrations of a mother trying to find a way out of inequalities—by a woman who bravely wrote it all down for her own need to create, at the same time to support a beloved family.

It is this blood and thunder in Alcott’s work that is fierce and bold, deserving of wider attention.

LaPlante, Eve. 2013. Marmee & Louisa: The Untold Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Mother. Simon & Schuster.

Ibid., p. 191

Cavarero, Adriana. 1995. In Spite of Plato. Polity Press. p. 8

To be extremely specific about it, here’s a sample list—asterisks are of course those women writing outside of the US: Maria Mitchell, astronomer: 1818-1889; Lucretia Mott: 1793-1880; Elizabeth Peabody: 1804-1894; Sophia Peabody: 1809-1871; Mary Tyler Mann (Peabody): 1806-1887; Sarah Hale: 1788-1879; Emma Willard: 1787-1870; Catharine Beecher: 1800-1878; Frances Sargent Osgood: 1811—1850; George Eliot*: 1819-1880; George Sand*: 1804-1876; Charlotte Brontë*: 1816-1855; Emily Brontë*: 1818-184; Anne Brontë*: 1820-1849; Harriet P. Spofford: 1835-1921; Elizabeth Drew Stoddard: 1823-1902; Frances Ellen Watkins Harper: 1825-1911; Rebecca Harding Davis: 1831-1910; Harriet Beecher Stowe: 1811-1896; Sarah Orne Jewett: 1815-1849; Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman: 1852-1930; Emma Lazarus: 1849-1887; Gail Hamilton: 1833-1896; Celia Thaxter: 1835-1894; Margaret Fuller: 1810-1850; Emily Dickinson: 1830-1886; Louisa May Alcott: 1832-1888; Abigail May Alcott: 1800-1877; Julia Ward Howe: 1819-1910; Elizabeth Barrett Browning: 1806-1861; Eliza Cook*: 1818-1889; Elizabeth Fries Ellet: 1818-1877; Anne Charlotte Lynch Botta: 1815-1891; Mary Elizabeth Mapes Dodge: 1831-1905; Delia Bacon: 1811-1859; Sara Jane Lippincott: 1823-1904; Kate Sanborn: 1839-1917; Anna Cora Mowatt: 1819-1870; Ann S. Stephens: 1810-1886; Lydia H. Sigourney: 1791-1865; Harriet Martineau*: 1802-1876; Maria Edgeworth: 1768-1849; Frederika Bremner: 1801-1865; Susan B. Anthony: 1820-1906; Elizabeth Cady Stanton: 1815-1902; Clara Barton: 1821-1912 (Founder of the Red Cross); Sara Grimké; Angelina Grimké: 1805-1879; Lucy Stone: 1818-1893; Amelia Bloomer: 1818-1894; Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell: 1821-191; Dr. Marie Elisabeth Zakrzewska: 1829-1902; Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler: 1831 – 1895; Dorothea Dix: 1802-1887; Matilda Joslyn Gage: 1826- 1898; Sojourner Truth: 1797-1883; Harriet Tubman: ca. 1820-1913; Mary Edwards Walker: 1832-1919; Victoria Woodhull: 1838-1927; Caroline Maria Seymour Severance: 1820–1914; Mary Corinna Putnam Jacobi (née Putnam): 1842 – 1906; Lucy Ellen Sewall: 1837 – 1890; Cordelia A. Greene: 1831 – 1905; Isabella Beecher Hooker: 1822 – 1907

Ibid., p. 153

Ibid., p. 157

p. 247

Ibid., p. 278

“a life of the hearth—of a hearth to leave and return to, back and forth—is anything but limited” SUCH a great read. Fierce, burning, powerful. Thank you!

Thanks really interesting essay - I knew nothing about Little Women until recently. I watched the Gerwig film a couple of weeks ago (after seeing Barbie, and I'd seen Little Bird when it came out as well, and thought that as excellent) and really enjoyed it.