The Right to a Name

Is it law or 'tradition' for a woman to change her name on marriage? It's neither.

My son is applying for college this fall. It’s a bit surreal. I’m excited for him, but also beginning to realize probable last things—as in, this will be the last year we decorate for Halloween with him, a holiday he loved to decorate for since he was tiny. Having those small recognitions as we move through this year is a strange mix of anxiety, wonder, fear, grief, and have-we-taught-you-enough panics—at the same time hugging him more often, which is of course endlessly annoying to a seventeen-year-old.

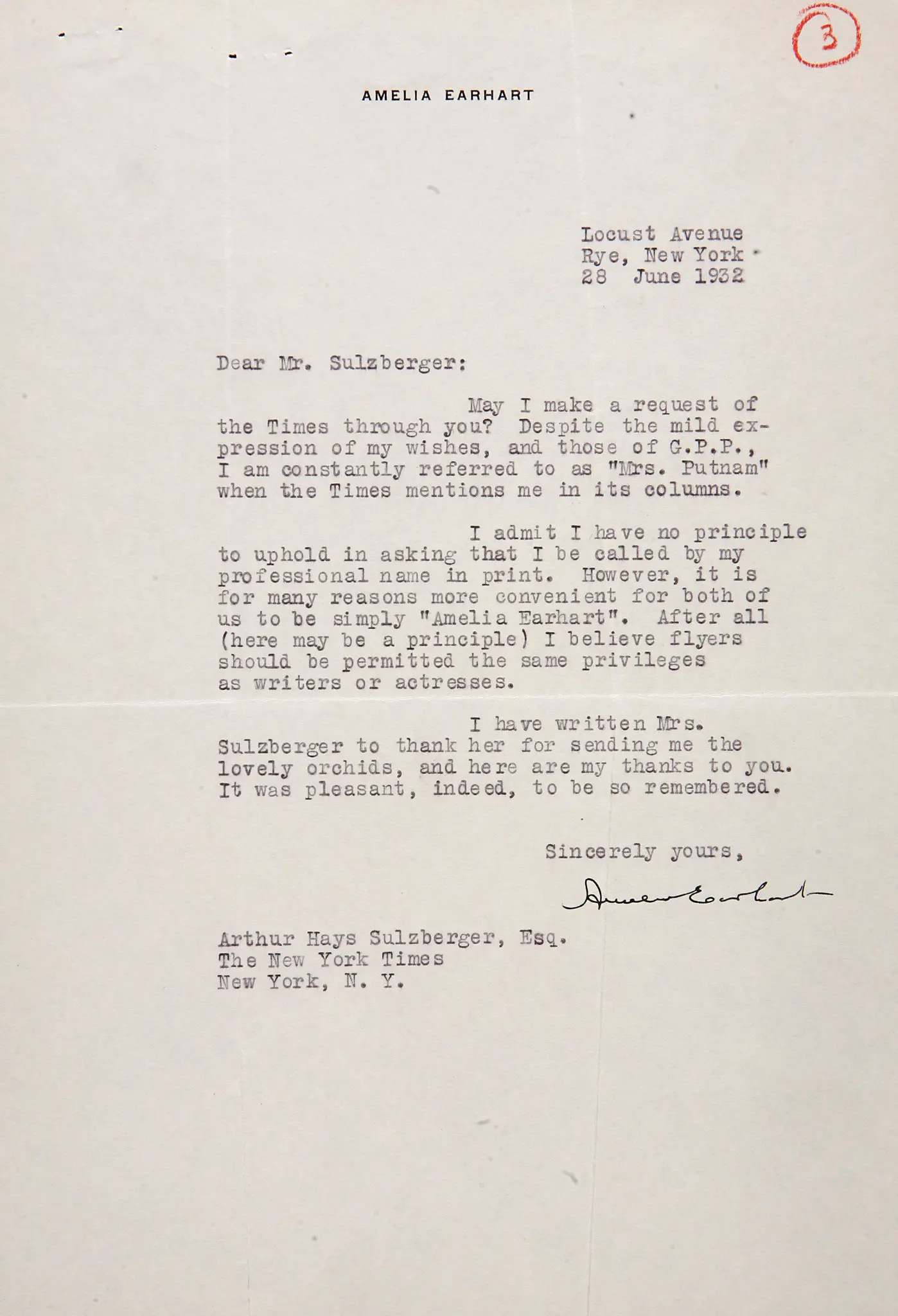

He began his application last weekend, and I helped him fill in details about his parents—e.g., highest degree obtained, birth date, profession, etc. When we got to my information, he had originally listed Mrs. from the drop-down menu of options, and I, well…threw a fit. And then I began to explain the history (I’m such a fun mom). My son defensively joke-yelled “Well I don’t know what these things mean, don’t look at me!!” I can’t decide if it’s a good sign that these things mean so little now that he wouldn’t know their meaning, or a sign that I’ve failed in my project to fully educate him on the history of patriarchy and misogyny. Oof. We laughed and I sighed, as I somewhat mock-furiously changed it to Ms.

I’ve used Ms. since I filled out my own college application. And yet there are always random mailings, or other occasions when Mrs. has been placed in front of my name, and it always grates—that reminder of being told my status as a wife is significant—while my spouse’s is not. For a large part of my younger life, I had planned to get a Ph.D.—because I love to study, but also, in truth, because I could set Dr. in front of my name and avoid the entire situation. Which I guess reflects how much these seeming ‘traditions’ can whittle away at the feelings of one’s worth and identity.

A couple of years ago I published an essay on the reasons I kept my name when I married—and the history of women writers whose identity was effectively erased, hidden behind men’s names.1

I was reminded of it again because the same week my son was filling in a corrected Ms., I came across this article on yet another new TikTok trend—women getting their birth2 names tattooed after marriage. Not only are a majority of women who marry opting to take their husband’s name in the year of our lord 2023, but they are also having their birth name branded onto their bodies.3

The supposed ‘tradition’ of women taking their husband’s name after marriage is a remnant of coverture—a practice cemented into existence by William Blackstone, who wrote the first book of common law, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765-1769), which was then used as the basis of law for England and the nascent United States. In many cases, American law follows Blackstone’s common law more strictly than the U.K.—as Alito’s liberal and errant use of Blackstone in his grotesque opinion overturning of Roe v. Wade made clear. On coverture, Blackstone wrote:

By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage…a man cannot grant any thing to his wife, or enter into covenant with her: for the grant would be to suppose her separate existence. [Women]…perform everything…under the protection and influence of her husband, her baron, or lord.

Yet as Alito invoked so-called legal precedents “deeply rooted in history” in his opinion overturning Roe, (which also cites the deeply problematic works of Matthew Hale4 and Edward Coke5 as further precedent), the only precedent that he actually followed was Blackstone’s practice of falsely citing ‘tradition’. Because coverture was not the rule of the land for centuries prior to the 1800s. It had to be established in law for it to finally take hold in social and legal practice.

English surname usage was much more flexible than much of history would have people believe, bearing little resemblance to what is actually ‘traditional.’

Names in early medieval England—for both men and women—often reflected personal traits, professions, status, skills, place, as well as family relations. When surnames began to be passed down to descendants, women often kept their own names, and in many cases were as likely to pass their names on to their children, and sometimes their husbands. Some of these are still familiar today—e.g., Madison (Maddy or Maud’s son) and Marriott (a middle English nickname for Mary).6

Much of these practices changed with the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. The principle of coverture originated in the 11th century but didn’t gain a strong social practice until the 14th - 16th centuries. A more equal and expansive framework that Anglo-Saxon women experienced prior to 1066 continued for peasant women after the conquest, but women of upper classes began to find themselves restricted to the rule of their husbands and lost the right to inherit or dispose of property. As Deborah Anthony writes:

Indeed, with respect to women the [early medieval] period appears “almost enlightened,” and “a study of Anglo-Saxon history might produce examples of women’s influence and freedom of action that would make aspects of even the twentieth century appear ‘dark.’”7

As women lost property rights, they also lost their names. Courtney Kenny, writing in 1879 on marital property rights in England, wrote that the erosion of women’s rights over the centuries resulted in “the wife sinking to being a ‘puppet of her husband’s will;” and that it represented a “revolution in the law of marriage.”8 Anthony puts an even finer point on it:

For roughly 800 years, English women underwent an extended period of decline in rights and status, with the most pronounced and abrupt shifts taking place in the early modern period beginning about the middle of the 17th century. That state of affairs became the foundational status quo at the establishment of the American colonies and eventually the new nation.9

Coverture policies and a woman having to surrender her birth name at marriage were not so much a ‘long-standing tradition,’ but ones that took centuries to fully reconfigure social practices. Calling medieval practices, well, medieval as a euphemism, and coverture and paternal surnames as a “long-standing tradition” is as much false advertising as naming the green island Iceland and the ice-covered one Greenland.

The flexible meaning of a woman’s identity is also reflected in the history of formal terms of address.

In 1755, Samuel Johnson—he of Boswell’s adoration—published a dictionary, with the following terms for mistress:

1. A woman who governs; correlative to subject or servant; 2. A woman skilled in anything; 3. A woman teacher; 4. A woman beloved and courted; 5. A term of contemptuous address; 6. A whore or concubine.10

While the hierarchy of definitions devolving into epithets is notable, if not expected, Johnson included no definition that meant “married woman.”

Mrs.—along with Ms.—was used as an abbreviation for Mistress in legal records and forms of address, parallel to Mr signifying Master. By the 14th - 15th centuries, Mrs. was the formal way to address adult women who were of elevated social status—such as business owners, a head of household, skilled worker, a head servant, as well as gentry. As Amy Erickson writes, Mrs.

described a social, rather than a marital status—when it wasn’t being used metaphorically…or contemptuously…11

Miss was also used as an abbreviation for Mistress, applied to young women of higher social status. Miss did denote the status of being unmarried, but until the 18th century, it was only applied to young girls, never women. Miss changed to Mrs with adulthood or the death of a mother, not marriage—its intention was to differentiate children from adults, similarly to how Master, used for young boys, shifted to Mr. when reaching adulthood.12

But this shifted in the Victorian era (surprise), as marital status became conflated with social status—when marriage was assumed the only real prize of status for a woman. And part of that shift followed the legal codification of coverture. Erickson writes of the shift in the use of Mrs. to signify marital status:

Both its introduction and its persistence deserve more scrutiny in terms of who was invested in that exclusive identification and why such an augmented indication of coverture was thought necessary or desirable in the nineteenth century.13

And still, Mrs. did not signify a married woman definitively until 1900.

Early modern historical records list surnames that reflect fathers, mothers, occupations, or familial status. Surnames of men could reflect their mothers: Margretson, Elynoreson, Wideweson; other female relatives: Marekyn (kinsman of Mary), Maggekin; or their status in reference to a woman (Modeles (motherless), Mariman (servant of Mary). There are records of wives having different surnames than their husbands, children with the mother’s name or their grandmother’s. They could also pass their name to their husband—when women still had access to inheritance and property.14 After all, Fanny Burney’s novel Cecilia, written in the late 18th century, had as its primary plot a heroine who, in order to keep her inheritance, had to find a man to marry who would take her family surname.

But this flexibility became rarer as coverture laws became more entrenched. By the 18th century—the time when Blackstone was publishing his treatise on common law—coverture and primogeniture (inheritance only through the male line) had come to be enforced in public and private life, across urban and rural populations. Despite a history of social practices to the contrary, Blackstone essentially “created English history while [he] also recorded it.”15

And with coverture frameworks enforced, the taking of a husband’s name at marriage became expected—because in coverture, marriage means one person—the husband. A woman becomes invisible, erased, a non-person without rights—to her body, will, wages, property, children. Men became the masters of households; women became mistresses for their husbands. And as a result, Mrs was more commonly used as a sign of a woman’s married status, rather than her skills, profession, or status. A woman’s status became only concerned with whether she was on the market or off—unmarried or married.

However, legally the common law never required surnames to only follow the husband/father (nor did it say anything against a man taking a woman’s surname). Despite this legal flexibility, the practice of a woman taking her husband’s name on marriage became ‘traditional’— particularly when women began to assert their rights to keep their birth name on marriage, such as Lucy Stone, who attended the Seneca Falls convention on women’s rights in 1848. When Stone and her husband married in 1855, their wedding vows were published as a manifesto of an equal partnership in marriage, and of her identity remaining the same.

Adding a more definitive touch to the erasure and the implication of Mrs as a married woman, the Mrs. Man type of address—as in Mrs. John Adams, rather than Mrs. Abigail Adams (which is how she was known and referred to herself in her letters)—that first appeared at the start of the nineteenth century and spread across social classes the next 75 years. Yet the Mrs. Man format was also challenged at the Seneca Falls Convention for Women’s Rights. Yet as recently as 1963, the Washington Post’s stylebook still decreed this ‘formal’ usage with some vehemence:

‘Mrs.’ is never used with the Christian name of a woman. It is Mrs. Walter C. Louchheim; Mrs. Louchheim; Katie Louchheim — NOT Mrs. Katie Louchheim.’16

As more women began to assert their right to keep their own name into the twentieth century, the legal response was “swift and negative.” As Anthony writes: “At times, the law is employed to enforce a tradition beginning to erode.”17

By 1881, a first-of-its-kind case in New York state court held that

by the common law among all English speaking people, a woman, upon her marriage, takes her husband’s surname. That becomes her legal name, and she ceases to be known by her maiden name. By that name she must sue and be sued…and execute all legal documents. Her maiden surname is absolutely lost, and she ceases to be known thereby.18

In the judge’s ruling against her claim, he noted:

holding that service of process against the defendant was improper as the person named did not legally exist.19

Dozens of other cases followed. In 1937, the Alabama Supreme Court took up the Mrs. Man format as the one required by law, stating:

[the] more perfect and complete identification of a married woman was one which used her husband’s first name as well as his surname, with the prefix Mrs. applied…20

Yet there is no legal precedent or law that states this. The Chapman case erroneously stated that a woman taking a man’s name in marriage was an “immemorial custom,” or “long and well-settled common law.”21 And Chapman became the benchmark, cited as precedent for countless other cases into the 1970s. These cases were in turn used by Departments of State to refuse passports to married women and women’s votes if they were not registered under their husband’s name. The same happened at immigration offices, post offices, banks, and the DMV.

One woman was suspended from her job with a county health department in 1974 for refusing to adopt her husband’s surname after marriage, supposedly violating the county’s mandatory “name change policy.” In a 1977 Texas court, one woman who petitioned to keep her birth name with the consent of her husband was refused on the basis that it

would be detrimental to the institution of the home and family life and contrary to the common law and customs of this state.22

Courts as late as the 1980s refused divorces on the basis that the wife was listed in paperwork under her birth name rather than her married name. And as recently as 2008, a woman running for office had a trial court strike her name from the ballot, calling it “misconduct” to have used her birth name instead of her husband’s name, despite no legal requirement to do so.23

In 1901, The Springfield Republican published an article—that was picked up by many other large national papers—that laid out the need for a designation that does not have to reveal or indicate a woman’s married status, suggesting the use of Ms. as a more neutral form of address. Nonetheless, the suggestion was buried.

The use of Ms. resurfaced in guides for business writing in the 1940s and 50s, but was still rarely used. Yet some critics continued throughout the twentieth century to fight the use of Mrs. or Miss—the writer William Empson argued in the 1950s that the use of Miss or Mrs inquires too closely into a woman’s life—writing:

the custom of writing [e.g.] “Madeleine Wallace” is a result of the Emancipation of Women. I do not know whether she is married, single, resuming her maiden name after a separation, or simply offering a pen-name; and it is not my business to inquire…What would be presumptuous…would be a demand to know before even addressing her whether she is ‘Mrs’ or ‘Miss.’24

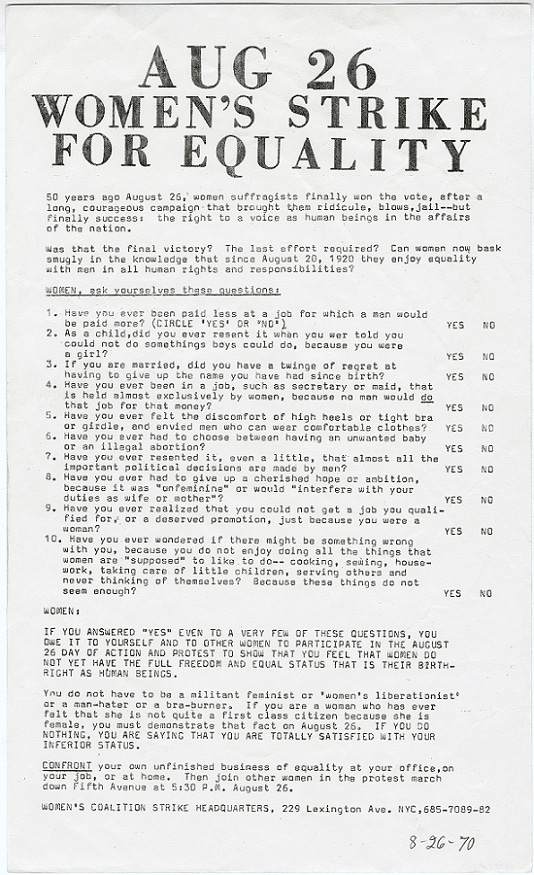

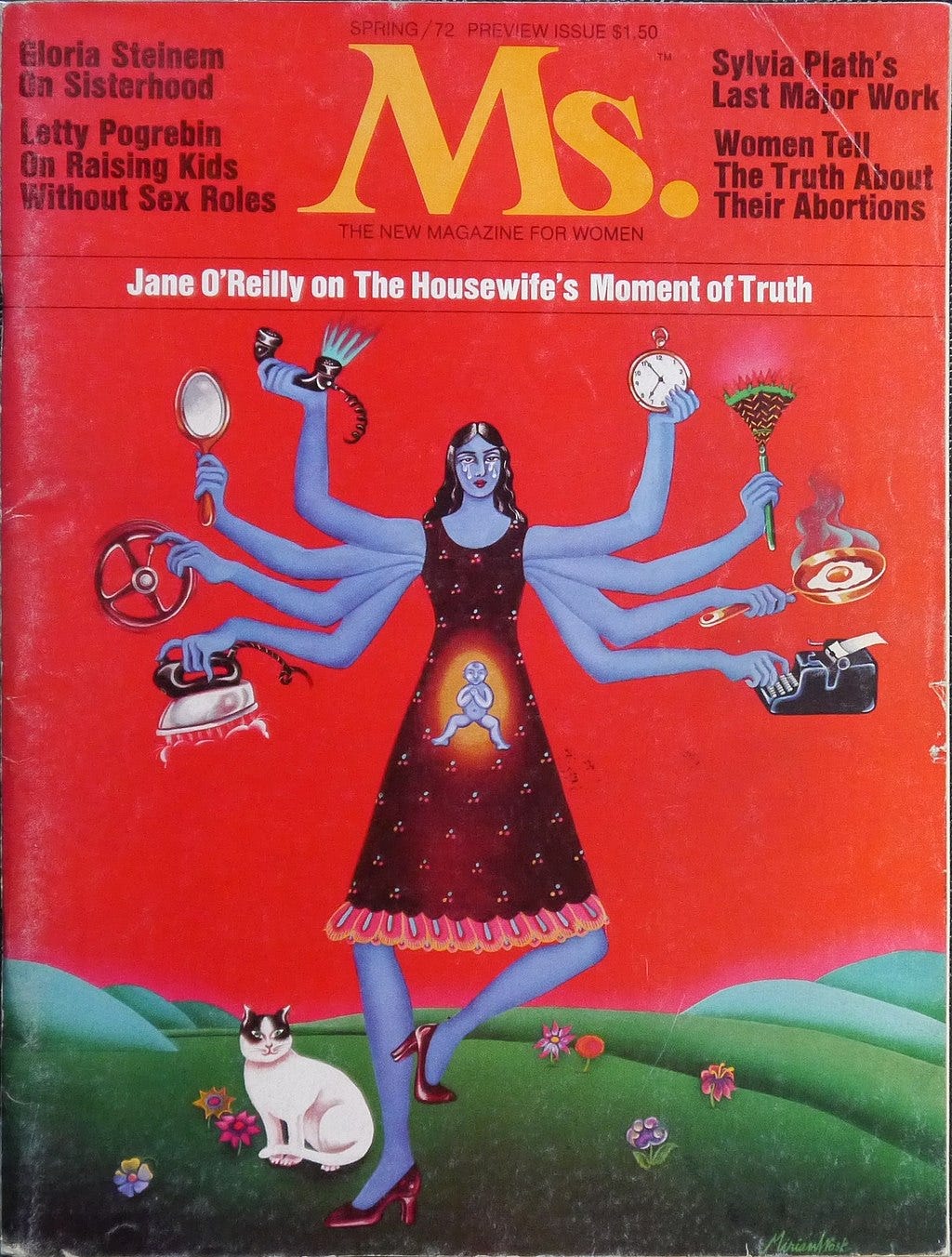

In 1961, Sheila Michaels started advocacy to demand the use of Ms. more widely. Her efforts didn’t take up any speed until a radio show in 1970—and later, at the 50th anniversary of suffrage with the Woman’s Strike for Equality. Soon Ms. stayed visible, becoming a symbol of the feminist movement. In 1971, Gloria Steinem and others started Ms. Magazine. And yet it wasn’t until 1986 that The New York Times shifted to the use of Ms. in its style guide—adopted by many newsrooms across the country.

And, in the ways that prove things are more circular than linear, Ms. essentially returned to the original form of Mrs. with one of the more common abbreviations for Mistress in the 17th century.25

[t]he idea of history as some inexorable process moving toward the perfection of the human species and an era of justice and tranquility is another of those figments of the human imagination wholly without precedent. —Herbert Hirsch26

Ideas of tradition become an easy way to dismiss social change, to lock social mores into a false, idealized wisdom of the past. While a ‘long-standing tradition’ of a woman surrendering her name on marriage is questionable at best, it’s one that is largely peculiar to the Anglophone world. Throughout the early modern period, England was the only country in Europe where women took their husbands’ surname. But by the 19th century it had spread to Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, as well as to British colonies and ex-colonies, as well as to parts of mainland Europe.27

And so, people assume ‘tradition’— “it’s just what has always been done.” They feel that they can’t change because it would be disrespectful to their family’s expectations, their husband’s expectations, society’s expectations. The practice is thought so traditional that it retrofits history to follow suit: a 1786 portrait of the writer Elizabeth Sheridan, nee Linley was exhibited first simply as Miss Lindley [sic], later Mrs Sheridan in the 19th century, and then became Mrs Richard Brinsley Sheridan when it was acquired in 1937 by the National Gallery in Washington DC. It remains that way today (in contrast to an engraving of the portrait at the National Portrait Gallery in the U.K.). The name she wrote under, performed under as a singer, and knew herself by, was erased.

And that’s the problem with the vague ‘traditions’ and assumptions about progress, about the past being backward from our own oh-so-sophisticated, age: it obscures the truth and retroactively creates a narrative of centuries of progress. It obscures the past when historians assume that Mrs. in a record signifies marital status—when in fact it referred to women in the past of social standing, some of whom never married, were heads of households, and were skilled professionals. Those stories become glossed over under the assumptions of simply “wife of.”

What grates at me is that changing a name is often treated as insignificant—a minor, incidental thing. But of course that’s not the case. People have known and argued for a different form of address, the right to keep one’s own name for centuries.

Because names are not insignificant—they have power. They are one of the many things stripped away in relationships of power and oppression. The use of the name MacGregor was banned in Scotland in 1603 after Jacobite conflicts. Indian boarding schools, along with all other atrocities, took away Indigenous children’s names. Enslaved people had to adopt the surnames of their owners. Identities forcibly obscured by ‘traditions’ of oppression.

And maybe that’s the most disturbing part about women being expected to surrender their birth names at marriage: it keeps patriarchal structures in place, both in the present, future, and the past. Ideas of history and cultural memory are molded and used to shore up beliefs and to refute shifting social ideals—which we now see with fervor, with book banning and history curricula being used as a weapon to obscure the past and control the future.

It should be everyone’s right to be called what they want, to have and keep their own identity. It relates to white-washing non-English names in the history of immigration, and of trans people having to endure dead naming. It’s a part of a society that refuses to accept what someone tells you about themselves. It’s a presumption that causes doubt and insecurity about one’s self, when your name or how you are addressed is decided by others. It’s a society that tells you not to believe yourself, that others can insist on telling you who you are.

I believe names have power. And I don’t at all fault women who take their husband’s name—because outside of patriarchy, it can be such a loving thing to share a name with one’s partner—whether you’re in a heteronormative relationship or an LGBTQ+ one. I just wish that the structures in place did not make it so much harder for men to change their names than they do for women. I wish that historians and others had a better grasp on how these ‘traditions’ should be interrogated so that we don’t perpetuate a narrative of absence, where women’s lives and stories continue to be hidden by titles of address or a husband’s name.

I keep thinking about what a different sense of the world I would have had growing up, learning that women were identified by their own names and status for centuries, not based on their marital status. That women of the past who were assumed to be wives were in fact professionals in guilds and business owners, not only wives or spinsters (a title that came into practice as a sign of a woman’s mastery of a skill, by the way). And that calling an entire millennium ‘dark,’ and the five hundred years (roughly) following as ‘enlightened’ is as much a manipulation of the past as it is when we are taught about progress and how much better off we are now. There is a much broader, more interesting story to tell than accepting that sexism, racism, heterosexuality, and binary gender are all ‘traditions’—the way it always has been and still should be. As Adrienne Rich wrote:

Until we can understand the assumptions in which we are drenched, we cannot know ourselves….We need to know the writing of the past, and know it differently than we have ever known it; not to pass on a tradition but to break its hold over us.28

I want to say up front that I think everyone should have a right to choose the name they want to be identified by—including women who do take their husband’s name. Every decision is personal and it should be everyone’s right to choose what and how they want to be called in this world. I just wish patriarchy wasn’t so much a part of it.

“Maiden” name is so problematic it could lead me on a whole new essay so I’ll just say that I’m using birthname to refer to the name someone is given …at birth.

That sounds more judgey than I want it to, and I think people—especially women and others who are marginalized by society—should do what they want with their bodies. And I love tattos! I just wish again…patriarchy….grrrr.

Matthew Hale (1609-1676) was a jurist and noble. Through his writings and legal proceedings, he sought to extend capital punishment to children fourteen and older—at a time when capital punishment involved, in many cases, being hung, drawn, and quartered. He believed that marital rape doesn’t exist, because (as his later colleague William Blackstone asserts) upon marriage, a woman is the property of the husband and has no legal rights. As husband and wife are one person, Hale argued, there is no way that rape can be perpetrated by a husband on a body that does not exist except as his own. Hale’s beliefs in this have been so influential in the courts and legal system that they were only dismantled in 1991 in England, and not until 1993 in the United States.

In 1662, Hale was also involved in one of the most notorious English witchcraft trials, where, as Lord Chief Justice of the Crown, he sentenced two women to death. The case was extremely influential across future witchcraft trials and convictions, and was used as a model for, and was referenced in, the Salem witch trials. G. Geis, writing in the British Journal of Law and Society, ties Hale's opinions on witchcraft directly to his writings on marital rape—an appalling implication confirming a belief in women as ghosts, of bodies that are not due any rights. Hale famously used the circular argument—without irony—that the existence of laws against witches is proof that witches exist.

Edward Coke (1552 - 1634), living a century before Hale, also had a hand in witchcraft trials. While he influenced the ideals of habeas corpus and the right to silence, in 1604 Coke broadened the Witchcraft Act to bring the death penalty without “benefit of clergy.” This expansion of the law effectively served to take those accused to execution without further delay—or chance of opposition or appeal. This was the statute that became enforced with fervor by the self-styled “Witchfinder General,” Matthew Hopkins, who accused and brought over 100 alleged witches to trial between the years 1644 and 1646, and with his colleague John Stearne, sent more accused people to be executed than all other so-called “witch-hunters” in the previous 160 years.

Anthony, Deborah J. 2016 “To Have and To Hold, and to Vanquish: Property and Inheritance in the History of Marriage and Surnames.” BR. J. Am. Leg. Studies 5. p. 218

Priscilla Ruth MacDougall, The Right of Women to Name their Children, 3 Law & INequ. 91, 138 (1985), (quoting Ruth Hale, “But What About the Postman?,” 54, The Bookman 560, 561, 1922). Quoted in Anthony, Deborah J. 2016. “To Have and to Hold, and to Vanquish: Property and Inheritance in the History of Marriage and Surnames.” BR. J. Am. Leg. Studies 5. p. 225

As quoted in Anthony, Deborah J. 2016. “To Have and To Hold, and to Vanquish: Property and Inheritance in the History of Marriage and Surnames.” BR. J. Am. Leg. Studies 5. p. 227

Anthony, Deborah J. 2018 “Eradicating Women’s Surnames: Law, Tradition, and the Politics of Memory.” Columbia Journal of Gender and Law. 37.1. p. 2

As quoted in Erickson, Amy Louise. 2014. “Mistresses and Marriage: or, a Short History of the Mrs,” History Workshop Journal, Volume 78, Issue 1, Autumn 2014, p. 3. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbt002

Erickson, Amy Louise. “Mistresses and Marriage: or, a Short History of the Mrs,” History Workshop Journal, Volume 78, Issue 1, Autumn 2014, p. 3. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbt002

Ibid., p. 4

Ibid. p. 15

Anthony, Deborah J. 2016. “To Have and to Hold, and to Vanquish: Property and Inheritance in the History of Marriage and Surnames.” BR. J. Am. Leg. Studies 5. p. 233-5

Anthony, Deborah J. 2018. “Eradicating Women’s Surnames: Law, Tradition, and the Politics of Memory.” Columbia Journal of Gender and Law. 37.1. p. 7

Anthony, Deborah J. 2018. p. 10

Chapman v. Phoenix Nat’l. Bank, 85 N.Y. 437, 449 (1881). Cited in Anthony, Deborah J. 2018. p. 11

Ibid.

Roberts v. Grayson, 173 SO 38,39 (Ala. 1937). Cited in Anthony, Deborah. J. 2018. p. 13

Anthony, Deborah J. 2018. p. 11

Ibid. p. 14

Ibid.

Erickson, Amy Louise. “Mistresses and Marriage: or, a Short History of the Mrs,” History Workshop Journal, Volume 78, Issue 1, Autumn 2014, p. 19 https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbt002

Ibid. p. 21

Herbert Hirsch. 1995. Genocide and the Politics of Memory: Studying Death to Preserve Life. p. 35. Quoted in Anthony, Deborah J. 2018. p. 3

Rich, A. (1972). When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision. College English, 34(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/375215

When I lived in Austria I had a long bureaucratic tangle with the electric company that serviced our apartment because at that time it was illegal for married couples to have different last names. I'd only been taking German for a couple of weeks and "I'm married" was one of the few phrases I knew. To which they responded, "You're not married" because I had a different last name!

My spouse and I admittedly had a huge argument about this before marriage. Fundamentally, I identify strongly with my name and didn't want to give that up. Plus, there are no males in my generation of either side of my family and my sisters and all my cousins took their husbands' names. My last name dies with me.

This was a fascinating history to read, Freya. Thank you for all your work on it.

In Hispanic culture, you give your children the name of the father and mother as a surname. The father’s surname followed by the mother’s surname. To honor the matriarchs of my family and to make it easier on me in American culture, my parents gave me three middle names. The maiden names of my mother and both grandmothers. (Webb is my mother’s , thus Jenovia’s Web.) It’s a lot. It barely fits on my passport, but I think it was a beautiful gesture and I’m proud to carry the names of my matriarchs with me.

When I marry, I will take my partner’s last name because I want to. ( I’m also not entirely sold on the institution of marriage, I think it’s very beautiful AND completely unnecessary unless you’re doing it for the tax breaks.) His surname is gorgeous, I’ve always loved it, and I’m looking forward to having a shorter name on my IDs. My partner has no feelings about it either way. He knows it is completely up to me whether or not I take his name.

I have the ‘Smith’ of Hispanic names and if we really want to get into the thick of it, it’s a Spanish colonizer’s name. My father was Purépecha.

I’m not attached to my surname at all. I’ve always felt my first name represents me the best and it’s tied to my identity much more than my last name. It feels more me than some generic last name I’ve inherited. Plus no one has to add my last name when referring to me. I’m usually the only Jenovia in the room, building, organization, etc.

Half of my friends that are married did not take their husband’s last name and felt no pressure to. I think it’s all silly when it comes down to it, marriage, last names. We are living in areas with made up borders on stolen land. To participate in this made up society we have to play the game a bit, that looks different for everyone. Most of us just go along without asking questions and without knowing the why. This was a wonderful, important read. Thank you, Freya.