I’m not generally what one would call a crafts person—I didn’t grow up learning how to sew or knit or do woodwork. The times that I’ve tried to learn, the attention to detail at some point gets the better of me and I give up in frustration. It’s not a part of my personality I’m proud of, but it’s real.

Nonetheless, I have made two quilts and some embroidery as gifts in certain parts of my life when I had the time and nerve to try and cultivate something over time, but these are generally aberrations—periods in my life when I had a wee bit more time on my hands. Funny, that phrase—because that’s what craft is: time spent working with one’s hands. Time in our hands slowed enough to give attention to what they might seek to do.

I chose to give a bit more time to sewing or making a quilt after a one-attempt failure at knitting. I still wanted to make something with my hands. There’s something about cloth and thread that made a bit of sense to me. And, at a time when I was living in a Norwegian winter, creating more items of warmth was always welcome. But still, I’m an impatient student, and while I from time to time tried to learn certain stitches, I fumbled my way through it in fits and starts.

But a project I’m working on now kind of blows the fits and starts out of the water—it’s a child-sized quilt that I began when my son was around a year old. Reader, he is now seventeen.

Over the years, the running joke became that maybe I could finish it before my son leaves for college. And like all good self-fulfilling prophecies, it appears that will probably be the case.

But there was a line in Tyson Yunkaporta’s book Sand Talk that has made me think differently about this slow-burn of a project, of making an object over time, of the various lines that connect the fits and starts in between. He writes:

People today will mostly focus on the points of connection, the nodes of interest like stars in the sky. But the real understanding comes in the spaces between, in the relational forces that connect and move the points.1

Perhaps the time involved—the length of time that my son moved from infant to child to adult—are the spaces between that connect the fits and starts. Maybe it’s all the forces in between start and starting again that moves it forward. Between all the stages of life as both parent and child.

The lines I’ve sewn by hand across the quilt represent connections between times of full-time career work, and the endless fight to not let work get in the way of being present for my child. The spaces when my son would ask me to read to him all afternoon as he snuggled up beside me in one small chair. Times I fell asleep from sheer exhaustion as I read aloud to him at bedtime, after workdays that demanded far too much. Lines that were sewn and then dropped when we took trips together. Spaces when we shed tears for our first dog, when my son was two and told me he could tell I was sad because the tears kept dropping out. Spaces where my son said funny, profound things when language was new to him that I would write down in a notebook to remember. The spaces of feeling his small hand in mine when he was young, and of conspiring together to adopt a chihuahua mix pup, and the delight of my son when our chi pup slept curled under his arm in bed. Spaces of schoolwork, practicing music, and hating the lessons—to last month, when he came home with an electric bass he bought of his own volition. Those memories and spaces of time are all a part of what has been threaded between in the making of this very non-skilled quilt.

Now that he’s applying for college, maybe it truly is the perfect time for the quilt to have one more spell of work before it can be finished.

The back of the quilt is made up of handkerchiefs with the layout of different cities I’ve loved. I liked the abstractness of the lines, and have always loved maps. And being in Anchorage, when I was younger I so often dreamt of traveling to cities—the anonymity, the bustle, being alone but in parallel play with so many others, someone always up no matter the hour.

So it’s funny that now, the quilt reflects things I thought were important as a newish mom—like the trips we were able to take, many that my son can barely remember. I used to love chances to travel but after the pandemic, my fervor for it has waned. Or maybe it was just stilled a bit, grateful for those earlier experiences and not as hungry to chase new ones. As much as I loved being able to visit faraway places, there is always something cognitively dissonant about waking up in my bed in the morning, knowing the next bed I reach for is thousands of miles away in a completely different place and timezone. I’m not sure we’re meant to move that fast.

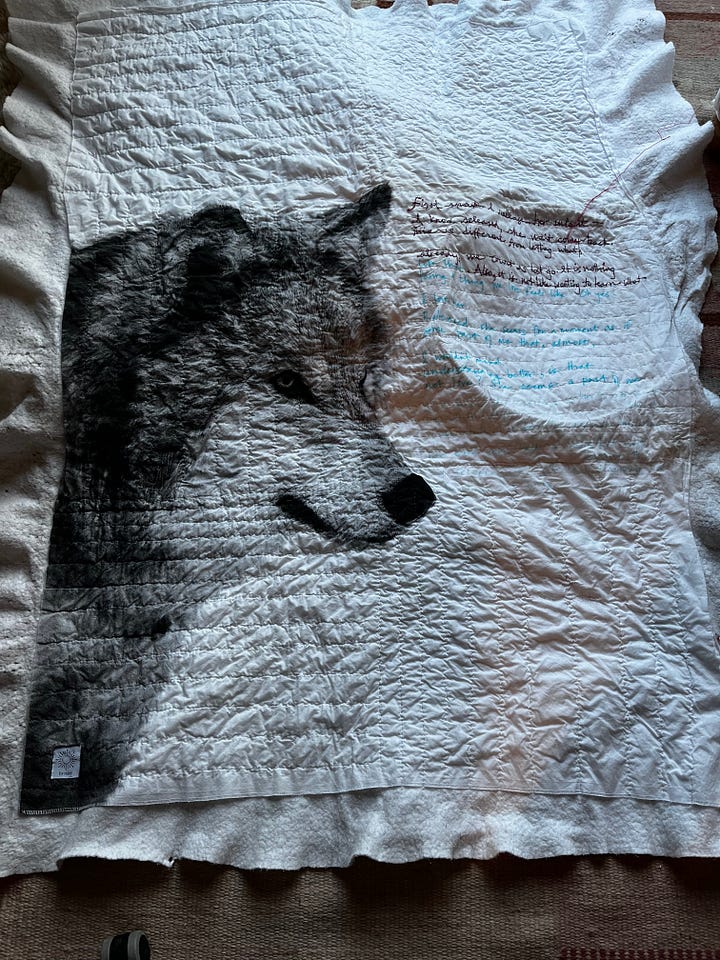

The other side of the quilt is a picture of a wolf—a favorite animal, and akin to our love of dogs that my son also shares—his first word was dog! He’s even named after our first dog2, so I loved that. I've quilted it by sewing lines across it—so simple(!). But the longest part has been figuring out how best to embroider a favorite dog poem—White Dog, by Carl Phillips3—onto the front. It’s taken some time to get it to work enough that I don’t get entirely disgusted and want to madly rip it out and try again.

Honestly, the sewn lettering in my already-mostly-inscrutable handwriting is beginning to look like the scrawl of a ransom note. It makes me laugh—such an obvious tell, that my patience for detail can only last long enough to sew but not enough somehow to make it look, well, finished. But in a way, that also feels like a sign of what it is and who it was made by—me, who is clumsy, impatient at times, still aspiring to make something with my hands as a gift. So maybe my son can someday look at the crazy writing embroidery of the poem and think yup, that’s my mom.

Writing and reading remain so much of the mind, that lately, I’ve come to crave time to be out of my head, to be more in my body. When talking about the bees she was keeping and writing poems about, Sylvia Plath said something about how poets live on air and that it was grounding to work in her body. I recognize something familiar in that. I think it’s why this time returning to it, I find myself enjoying the craft of sewing—creating from the body, hands over time, working the thread along the letters of a poem that never fails to make me catch my breath—the interplay between thought and thread and word becoming a kind of spell.

Yunkaporta created an object as he began each section as a way to frame his book, thinking and dreaming as he crafted, needing the work of the hands and body together with the mind to find a way to guide his thoughts into words. It’s a beautiful way to think about words and writing—and the space and time needed to bind them together. But it’s also the joy of working slowly to make something needed, useful, artful. To create through a process that takes time from beginning to end—the connection between being as meaningful—and essential—as the finished work. He later writes:

Your culture is not what your hands touch or make—it's what moves your hands.4

In ancient Greek there was no distinction made between craft, art, and technology. It was all techne—carpentry, sculpting, medicine, painting. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy states:

I find it so interesting that the relationship between reason, ends, and action is there in the definition—a kind of echoing dialectic with how Yunkaporta writes about making, creating—of noticing the spaces of connection between.

When industrialization came about, techne became the etymological root of the word technology, coming to mean the thing by which objects were produced, other than that which was made by human hands.

Alexander Langlands, in his book Cræft, writes about the roots of the word craft and how it originally meant ‘power, strength’ in Old English.5 The etymology turned towards the power, strength in a human hand to make something—and craft widened to become “skill, dexterity; art, science, talent” (via a notion of “mental power”), which by late Old English led to the meaning “trade, handicraft, employment requiring special skill or dexterity,” also “something built or made.”6

Langlands feels the industrial age essentially caused an “illiteracy of power”—we lost the knowledge of what our hands can create. We are now so accustomed to pressing a button to start a car, flip a light switch to instantly dispel the darkness—tasks that took bodily movement, preparation, collaboration, strength in the past (e.g., walking!7 or knowing how to care for and ride a horse; keeping bees to make candles, or gathering materials for lamps, how to procure the oil, trim wicks, etc.). There is no longer a real familiarity with the power of our own hands. He writes:

The point when industrial processes emerged as the dominant means of production was the point at which the concept of craft as a form of art emerged— as a self-conscious counterpoint to factory-made goods. Craft became defined in opposition to industrial manufacture.8

The work of the hands became craft—things to do only in the spaces between work and consuming objects, relegated to being called ‘hobbies.’ Yunkaporta also talks about this shift, but in light of colonization and Indigenous practices:

I am often told that I should be grateful for the progress that Western civilization has brought to these shores. I am not. This life of work-or-die is not an improvement on preinvasion living, which involved only a few hours of work a day for shelter and sustenance, performing tasks that people do now for leisure activities on their yearly vacations: fishing, collecting plants, hunting, camping, so forth. The rest of the day was for fun, strengthening relationships, ritual and ceremony, cultural expression, intellectual pursuits, and the expert crafting of exceptional objects.9

How ironic that we value what is handmade because we no longer have the skill and lifelong knowledge, gained by practice, passed from generation to generation, to make things ourselves or in community. Because we are conditioned into a work-or-die life with no time to create for ourselves, in an economy that is intent on office hours and productivity. Corporations aggrandize wealth as we work for them so that we can buy out of competition and the illusion of scarcity, to keep earning and buying more. And as a result, people find it quaint to make their own bread, nurture sourdough over years, or know how to carve wood, let alone how to spin wool into thread that then needs to be worked further to become a blanket or sweater or cloth.

What I also learned I like about the long-making of this quilt is how the repeated actions become a ritual—threading the needle, tying the knot, beginning again, stitch after stitch. It’s not unlike poetry or chant or any rhythmic speech or song that repeats, making tracks of memory in your mind, taking clear shape in our heads. Like the transfer of a song, prayer, poetry that moves between breaths, between speaker and listener/writer and reader through repetition, rhyme. There’s something meta about sewing a poem into the cloth, the hands making repeated gestures across lines of enjambment and form, that work together in a way of remembering.

Rituals are also a way to mark a punctuation in a journey, or a life, or an experience. An act that gets remembered, even if only by one person, and the relationship of our bodies to that space around us, the place we are as we carry out what has become a repeating pattern.

The quilt has become an act of ritual, revisited over so many years, made up of poetry, my son, places we’ve visited, times we’ve all shared, and always a love of dogs. A ritual that connects the spaces in between into something larger—patterns of love and memory.

All of this is to say that this long-making is telling me something I didn’t recognize until I began to think about the years between—and also of the years before—the generations and traditions of people who are a part of any work of sewing, quilting. And so now, instead of being embarrassed about how long it has taken to finish a quilt in a world that makes no time for such things, I grew to love more and more that it has been an object to return to, to keep working on, to have these traditions and memories—from the wider past to the very personal past and present—be a part of each stitch.

I now love that it has become a small story, a joke in our family, and an object, unfinished in the background to return to. The repetition becoming ritual, making tracks of memory that have become familiar, stronger, for the length of the making. I can now see the patterns, the spaces in between that connect the whole, where the meaning lives.

Yunkaporta, Tyson. Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. 2020. Harper Collins, New York, NY. p. 79

It’s a bit of a family tradition. My grandfather insisted on calling my dad by the name of his favorite hunting dog, a name that bears no relationship to my dad’s formal name, and it has been my dad’s name his whole life. Since I adore and admire and revere dogs so much, we thought of doing the same when we named our son, as a way to honor both our son, first dog, and family. Some people when they learn this they’re a little disgusted—named after what?? But dog people always respond with something akin to O! That’s so beautiful!

Yunkaporta, Tyson. p. 242

In many Germanic-based languages, like Norwegian, kraft is still the word for power…

Yunkaporta, Tyson. p. 140

I know how much my soul appreciated all of this because I feel a slowdown in my words and a settled feeling in my mind. Thank you! (Also, ha, yes, walking!)

What a beautiful piece you have woven here Freya - both the writing and the quilt.

A sense of nostalgia arose in me as I read. That reminder of my son's ( now 18 and just had first year at University :-) ) hand in mine when he was little. The soft innocent warm entwining of his trusting clasp enclosed in my supposedly older and wiser hand.

This quilt is, and will be, such a precious gift to your son and yourself. Seems like the Universe knew that it was something that needed to take time for that story to unfold.

Thank you for sharing this heart felt story. Jo 🩵